Additional Information

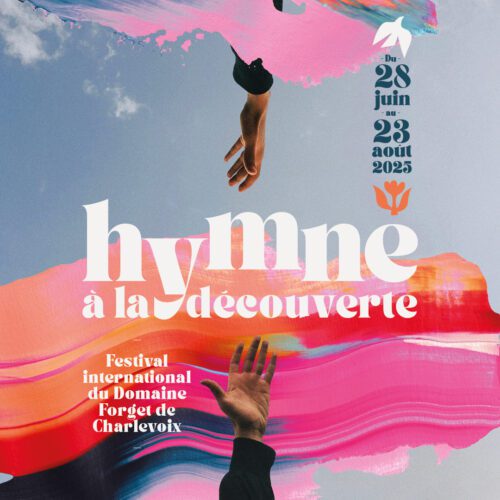

A particularly festive atmosphere will enliven the Esplanade Tranquille this Saturday during the Virée classique. Oktopus, an octet combining Eastern European and classical music, will take the stage to offer a new perspective on a number of works from the repertoire. Brahms, Liszt, Mahler, Bartok and Enesco will be drawn into the dance, and the folk roots of their music will be brought to the spotlight.

The result of in-depth research and a passion for klezmer music, Oktopus offers a show accessible to all, sometimes festive, sometimes melancholy, but always optimistic and vibrant. A reflection of the city’s diversity, Oktopus stands at the crossroads of many fascinating musical traditions. PAN M 360 had the chance to speak with Gabriel Paquin-Buki, arranger, composer and clarinettist for Oktopus.

PAN M 360: Hello Gabriel! So, to begin with, Oktopus formed in 2010 and has since made a name for itself on the world music scene in Quebec, Canada and internationally. What is the essence of the music of this ensemble, whose influences sometimes seem to be at odds with one another? What is the guiding principle?

GABRIEL PAQUIN-BUKI: Yes, the music we base ourselves on first and foremost is certainly klezmer music, in other words, the music of the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe. On the other hand, as some people have already done, such as Itzhak Perlman before us, we take a slightly more classical approach to this music. In fact, it wasn’t even a choice, since the musicians in the ensemble were classical musicians. We’re not basically folk musicians. It’s not a tradition that was shared with us or passed on orally by our parents. We went back to klezmer music in its folk roots, but also to Eastern European music in general, especially at times when folk music was closer to classical music, in the late Romantic period in particular.

PAN M 360: You’re musicians with a classical background, not a folk background. So, why do you do klezmer music, which is not your basic musical background?

GABRIEL PAQUIN-BUKI: Initially, when we started out as university students, it was just a form of music that particularly appealed to us. I suggested it to the others because it’s music I’d listened to since I was very young, music that had rocked my childhood. And when I went to see Klezmer music shows, I literally vibrated. So I wanted to perform it myself. That’s what it’s all about. It’s a music that came to us in a particular way, that we wanted to interpret and to which we wanted to add our grain of salt.

It’s music that’s very, very accessible. There’s folk music that’s just as good but requires perhaps a little more effort to understand or appreciate. Klezmer music is very, very accessible. There are certain elements that are shared with everyday music. I think it’s music that also knows how to touch people’s hearts. It’s a very old music. That may explain its popularity.

PAN M 360: The Klezmer musical tradition seems to be deeply rooted in an atmosphere of festivity and celebration. Is this really the case? Is there a contrast between the message and the music perceived by less familiar ears?

GABRIEL PAQUIN-BUKI: Yes, it’s true that this music has developed enormously in the context of weddings. So there’s an undeniable festive side to it. However, not all wedding music was festive. There are moments in the more religious tradition, for example, when a woman was told that she was losing her maiden status and that with marriage came all the obligations and all the trimmings, which is a more introspective moment of marriage. So there’s a whole slower, more melancholy side to klezmer music, with slower dances.

It’s also a music that bears witness to the history of the Jewish people. It’s a people who have been enormously persecuted. So their music can’t just be festive. Often, the joyful, festive aspect comes at the end. In other words, no matter what the tragedy, no matter what the misfortune, no matter what the persecution, no one is going to take away the possibility of celebrating, of getting together, of dancing. So, it always ends up a bit festive, but as you mentioned, that’s often just what we’ve kept. It’s become a bit of a cliché of music, sometimes, even circus music, whereas there’s a huge repertoire, a huge part of that culture that’s much more introspective and darker, slower.

PAN M 360: There’s a perpetual tension between so-called scholarly music and folk music. We’re generally used to hearing and talking about what classical composers have borrowed from folklore, but Oktopus seems to be doing the opposite. Is the process similar or fundamentally different? Are we talking about inspiration, influence, parody, emulation, hybridization?

GABRIEL PAQUIN-BUKI: There are a lot of composers who are inspired by folk music, taking only certain elements from it. Sometimes it’s just a melody, or maybe a certain accompaniment that gives their work a bit of liveliness. But in fact, folk music has many defining elements. Rhythm, melody, ornamentation, improvisation. You can’t really separate them. With Oktopus, what we’re trying to do is to rediscover some of that folk essence that lies at the heart of classical works. This is the case, for example, with one of the works we play, Enesco’s Romanian Rhapsody. In fact, Enesco composed almost nothing. He orchestrated a lot, but it’s all folk tunes. But to build up his orchestral work, he had no choice but to abandon ornamentation and improvisation, because there are so many musicians playing together, led by a conductor. You can’t just start improvising as you please. Basically, with Oktopus, we’re going to look for those folk traditions that inspired the composers, but bring back what they were obliged to leave out, i.e. ornamentation, improvisation and certain rhythms too, which are sometimes irregular.

Dance is intimately linked to folk music. For us, it’s an element we explore less because we don’t play in a dance context, and we don’t have a dancer with us, but once again it’s two things that were intimately linked to folk music. We were almost always there to accompany dancers. But just knowing that has its impact. Singing, too. Precisely, in our Enesco rhapsody on the album, we recovered the Romanian chant that was originally associated with Enesco’s theme.

PAN M 360: La Virée classique has incorporated a “World” component for some years now, and this year seems to place even greater emphasis on mixing music from different origins. Do you think these mixtures will become more and more frequent, or will concert audiences still seek some form of partition between Western and non-Western music?

GABRIEL PAQUIN-BUKI: I have the impression that it’s going to become more and more frequent, because it’s really in the spirit of the times, but it’s also so much more representative of the metropolis that is Montreal, the hub where so many cultures rub shoulders. It’s also an unhoped-for opportunity to give different stages and musical contexts to so-called world music, to mixed music, because there’s a bit of a cliché where the Maison Symphonique is reserved for classical music and the Bar à Jojo is devoted to folk music. I’m exaggerating a little, but in the OSM’s last season, an Iranian ensemble came to present a few works on the Maison Symphonique stage, and it was absolutely incredible. Above all, it helps people understand that there is classical music from many other traditions. Sometimes, folklore is also a perfectly legitimate tradition taught in conservatories. I think it’s time for this kind of music to find its way into classical programming. I also think it’s very entertaining for the public. I have the impression that projects like Oktopus are going to delight certain classical programmers who want to get off the beaten track a bit, with the usual string quartets and piano sonatas.

PAN M 360: Your concert at the Quiet Esplanade features different arrangements of Romantic composers (Brahms, Liszt, Mahler) as well as Bartók, who made extensive use of folk music in his works. What’s special about his arrangements? How can we give them a new “Oktopus”-style dress? What can we expect when we go to the concert?

GABRIEL PAQUIN-BUKI: There are two approaches. One is more serious. Let me take the Enesco example again. In that case, it was really a matter of finding all the themes that inspired the composer, finding the folk version and then incorporating these folk elements into the arrangement. For example, the rhapsody ends with a theme called “Ciocârlia”, which means lark in Romanian. In the original version, the solo violin does a bird solo. All he has to do is imitate a bird with his violin. We brought that back. Of course, in the orchestra, we’d imagine a little less of that. Really, what we did was to work a little more methodologically, to see each of the themes, where they came from, then how we could incorporate them into Enesco’s work, and then create something that really straddled the line between his orchestration and the original themes. The other approach is a little more superficial. If it’s a work you really like, you want to give it a completely different personality. It’s less musicological, I mean, but simply, if you took an eighth note out of that theme, it would be really great. In Bartók, for example, there’s a passage where you just turn a 4-4 into a 7-8. Irregular rhythms are characteristic of Eastern European music and much less so in Western music, but it’s not something we went to Romania to check out. We sometimes like to bring these rhythms back.

We have an arrangement by Francis Pigeon of Saint-Saëns’s Bacchanale, which is a very good example of Orientalism. Saint-Saëns really fell in love with this scale, which is found all over the world, but very rarely in classical music. Some call it the Jewish scale, others call it “Hijaz”. For him, it was based on a mode, an Arabic maqam. We used that mode and then amplified it by showing how it was used in the various types of music of the Maghreb and Eastern Europe. This brings out the orientalist side that Saint-Saëns wanted to give to the work. So it depends on the work. As I say, sometimes there’s a pretty serious work behind it, and then sometimes you want to do it in a crazy way, and then you find the best way to do it.

PAN M 360: Did Oktopus carry out any musicological or ethnomusicological research to ensure the authenticity of its music?

GABRIEL PAQUIN-BUKI: The group did its homework in the sense that we went out to meet folk musicians and then worked on the ornament and style because sometimes you get the impression that you’re just interpreting other people’s music without any real work. A lot of people do, and that’s okay too, but in Klezmer music camps, courses, master classes, etc., we’ve worked to ensure that despite their classical training, musicians still have a solid folk base.

PAN M 360: What is your objective for this concert? Get people moving? Demonstrate the versatility of Klezmer music? Present the “classics” in a new light?

GABRIEL PAQUIN-BUKI: Certainly, people are experiencing a moment beyond their expectations. I would say to perhaps open up the vision of folk music in classical music, to see that the boundaries are not so watertight and that, in fact, classical music is built on so many elements from popular music, from folklore. There are some really special moments that can happen in our shows. One time, we were performing at a Balkan Party at Le Cercle, in Quebec City, and there was a mosh pit while we performed a Romanian dance by Bartók, la rapide. We’re very proud of that, to have had a mosh pit to Bartók. So we’re really open to any reaction from the audience.

Oktopus will perform at the Esplanade Tranquille on Saturday, August 19 at 1:30 pm, and at 7 pm. For more information, the complete free programming can be found HERE.