Additional Information

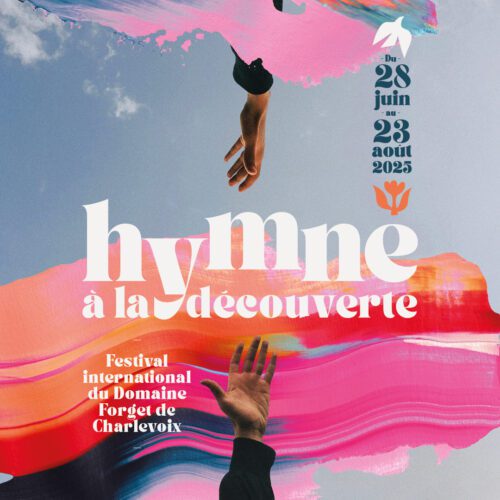

After dazzling audiences and critics alike in 2023 at the Festival de Lanaudière with Monteverdi’s masterful Orfeo, conductor Leonardo Garcia Alarcon and his Capella Mediterranea are back in 2025, on July 6 at the Amphitheatre. This time, Monteverdi’s final opera, The Coronation of Poppea, will be performed with more or less the same soloists, but a more sparing orchestra. I spoke to the conductor about this, and also about a second concert he will be giving on July 8, entitled Monteverdi and the Seven Deadly Sins. In three questions and answers, plunge into the world of Monteverdi, before being immersed in his music.

PanM360: Orfeo is a revolutionary opera, which Monteverdi created in the prime of life, at the age of 40. The Coronation of Poppea dates from the year before his death at the age of 76 in 1643. What are the differences between the two musical worlds?

Leonardo Garcia Alarcon: A lot has changed. In 1642, we are past 1637, which saw the creation of the first public opera in Venice, for which the composer wrote Poppea. So Monteverdi was writing for people who were generally younger and more diverse. Those people brought their dogs, they talked, they laughed—it was almost like a circus! Monteverdi adopted a more direct style, resorting to fashionable practices such as cross-dressing, and introduced parallel, lighter love stories known as ‘love satellites.’ Comedy also played an important role, as Monteverdi adapted to the popular style of commedia dell’arte.

Quite the opposite of Orfeo, written for the Court of Mantua, which is an almost sacred opera, in which the characters are associated with the ethical foundations of humanity, with questions of life and death. We ask ourselves how to resolve the passage from one state to the other, and we hear that the answer is music (even if, in the end, it fails). In reality, we are still in a Renaissance world. Poppea takes the audience elsewhere. For the first time in opera, we see and hear historical characters who really existed, not gods or myths. The ‘divine’ forces are still present (Virtue, Fortune and Love, who squabble over which has the most influence over humans), but the central roles are still played by historical figures, Nero, Poppea, Seneca, etc.

The social context was also different. The Opera aroused the mistrust, even hostility, of the Pope. In fact, the Pope cancelled the institution in Rome. But Venice jealously guarded its independence, and so took the liberty of standing up to the Pope. Poppea was therefore a major step forward for the new artform. Finally, opera is now a business. You have to sell tickets, and you have to keep production costs to a minimum in order to be profitable! That’s why we can’t afford a huge orchestra like in Orfeo at the time. Meanwhile, the composer Francesco Cavalli was writing operas that were ruining him, so much so that production costs were outstripping income. He was forced to marry a rich lady who acted as his patron! So, all the rules of business are becoming inevitable.

PanM360: Let’s talk about the orchestration of Poppea. It has been a problem for a long time. Nikolaus Harnoncourt studied the subject extensively and left a famous vision of the thing. But it remains personal. So you had to make some choices. Which ones and why?

Leonardo Garcia Alarcon: Harnoncourt clearly opts for an Orfeo-style construction, with a large orchestra. This is also the nature of one of the manuscripts that have come down to us, which corresponds to a score owned by Cavalli (the composer mentioned earlier). It is a more sumptuous version of the writing, probably used for performances in Naples. Ironically, this version contributed to the birth and subsequent flourishing of so-called “Neapolitan” opera. For my part, I have chosen to work closer to the original, the one from the premiere, which is not available, but from which we can deduce the outlines. These give us information about a relatively small orchestra. For the economic reasons mentioned earlier. To this I have added a few colours that are not foreign to Monteverdi, when we know what power of suggestion he gave to various instruments in the transmission of precise emotions. We can therefore assume a very small orchestra, with two violins, a lute (or two) and a harpsichord, to which my personal choice adds cornets, flutes and a harp. It seems to me that this corresponds both to a very precise historical situation and to a well-argued expressive ideal.

PanM360: That’s on July 6 at 4 p.m. at the Amphithéâtre. On July 8, at the Saint-Jacques church, you’ll be giving Monteverdi and the Seven Deadly Sins. What is it, and why do it?

Leonardo Garcia Alarcon: The idea for this programme came to me when I was doing a long residency at the Teatro Malibran in Venice. It’s a superb place, where you’re surrounded by magnificent works of art, many of them on the theme of the deadly sins. I made the connection with the time of the composition of The Coronation of Poppea, during which Monteverdi also wrote La selva morale e spirituale. La selva is like an antithesis to Poppea. It is moral and virtuous, while Poppea is quite the opposite. So, a bit like the Deadly Sins vs the Cardinal Virtues. Knowing that the Seven Deadly Sins are a papal creation from the 13th century (Italian, in other words), I thought it would be fascinating to delve into Monteverdi’s entire operatic, sacred and popular repertoire in order to extract the parts that illustrate each of these aspects, and then put together a coherent programme. And then there’s something even more fascinating about these loathed faults than the “desirable” virtues. They invite drama and powerful emotions. Just as today we know far more about Dante’s Inferno than his Paradise, which is of no interest to us at all.

DETAILS FOR L’INCORONAZION DI POPPEA, 6 JULY AT THE FESTIVAL DE LANAUDIÈRE

DETAILS FOR MONTEVERDI AND THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS, 8 JULY AT THE LANAUDIÈRE FESTIVAL

Artistes

Sophie Junker, soprano (Poppea)

Nicolò Balducci, countertenor (Nerone)

Mariana Flores, soprano (Ottavia, Virtú)

Christopher Lowrey, countertenor (Ottone)

Edward Grint, bass-baritone (Seneca)

Samuel Boden, tenor (Arnalta, Nutrice, Damigella, Famigliare I)

Lucía Martín Cartón, soprano (Fortuna, Drusilla)

Juliette Mey, mezzo-soprano (Amore, Valletto)

Valerio Contaldo, tenor (Lucano, Soldato I, Famigliare II, Tribuno)

Riccardo Romeo, tenor (Liberto, Soldato II, Tribuno)

Yannis François, bass-baritone (Mercurio, Littore, Famigliare III)

Cappella Mediterranea

Leonardo García Alarcón, conductor