Additional Information

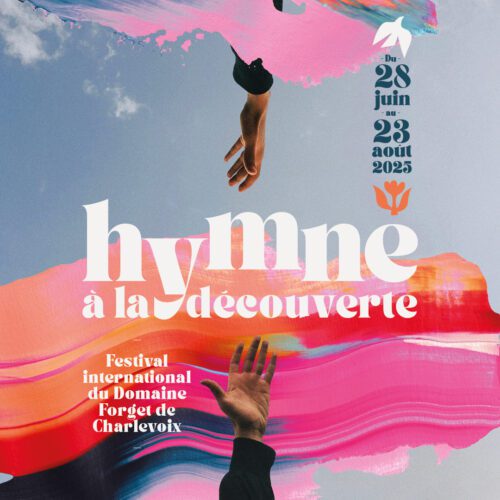

Back at the Lanaudière Festival for a first time since 2019, the illustrious violinist Christian Tetzlaff takes on one of the summits of solo violin literature: the JS Bach complete Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, BWV 1001–1006. We must acknowledge that

this performance offered by this fantastic German violinist will be a physical and intellectual challenge that just a few concert soloists accept. So we’re looking forward to attending this rendez-vous with Bach and Christian Tetzlaff in the intimacy of one of Lanaudière’s most beautiful churches, at the lovely village of Saint-Alphonse-de-Rodriguez. Just a few minutes before his flight to Quebec, Alain Brunet could reach the renowned violinist and have a chat about playing Bach.

PAN M 360: Christian Tetzlaff, you are going to perform in a church located in the lovely village at Saint-Alphonse-de-Rodriguez in the Lanaudière county. You will play what you recorded in 2017, the JS Bach complete sonata and partitas for violon. Of cours, you played those pieces many times before and after this Virgin recording

Christian Tetzlaff: Yeah. I played those pieces over more than 40 years and I played them as a complete cycle for 20 years. It’s the most beautiful and rewarding thing because Bach gets a continuous story in the six pieces, a journey into deep darkness in the D minor Partita in Chaconne and then some kind of feeling of resurrection in the C major and E major and to follow that whole thought that is like a gigantic Bruckner symphony and it goes through all kinds of emotions and physical feelings a human being can have. So, it’s totally fulfilling. Yeah, well, when you play the complete Sonata and Partita works from Bach, as you say, it’s a long journey.

PAN M 360: It’s probably an ongoing process as an interpreter of JS Bach, during your own life.

Christian Tetzlaff: Yes, it is a steady companion, I have to say.

PAN M 360: And how do you see the evolution of your playing through those pieces?

Christian Tetzlaff: Well, like most things, I think the older you get, the simpler and the more direct you get if you allow yourself to be emotionally free. So, I think what I play now is more direct, easier to follow for the audience and more outwardly emotional about knowing what the composer is talking about and trying to find sounds that really convey it nicely. And everything, yeah, naive and easy and the dancey bits more dancey and the dark bits darker. That’s my feeling towards how it has developed over the decades.

PAN M 360: How can we pinpoint the elements of the personality of the violinist when he plays those great and immortal pieces? In your case, do you pinpoint some elements of your personality sometimes?

Christian Tetzlaff: I hope as little as possible. I hope the idea of the interpreter is to immerse himself into Bach and his music and let it go through him to the audience. And the more you hear, oh, he’s doing this, he’s doing there, and he’s using vibrato here and not there, the less good it is. I should be as much a listener as the audience is. That’s my ideal.

PAN M 360: The concept of interpreting those partitas and sonatas has changed also through the years.

Christian Tetzlaff: And certainly not this idea that one’s doing something that speaks out or that is different from other people. Nowadays we are in a time where we have these decades of gathering knowledge about how it was performed and what it meant at that time and how the Baroque era feels somehow. We have these things all inside of the system, because when I started playing these pieces, one couldn’t listen to them properly because it was all about violin playing and majestic chords and impeccable playing.

And nowadays it’s about making music, dancing and singing. So this is a beautiful process which I have actually lived through in my own lifespan from starting in the 70s playing them. And it’s good to see we are in the best time where we can be free with them, but on the basis of their musicality.

If you listen to the Bach Cantatas, you see for every text, for every Cantata, he uses completely different instruments, completely different composing styles, and this freedom in expression to be always excessive and to the point of saying something that is something that we can transfer nowadays into the violin.

PAN M 360: So through the times since the Baroque period when Bach composed those partitas and sonatas for violin, how can we see the evolution of the interpretation of those pieces through the periods, through the epochs?

Christian Tetzlaff: I mean, it’s quite atrocious to see what has been done, because violin playing has been so much about the superstar and about the technical ability and the biggest sound and the broadest data, that when you listen to the first recordings that we have, or maybe not the first days, there’s something good, but from the 50s and 60s and 70s, the music behind it is unrecognizable for me, because it is about mastering weird bowing techniques, playing those chords, those four chords divided in two and two. I mean, there was such a distance to what this music is talking about, and that music can be also wild and can also be at times not beautiful, but deep and dark or overjoyed, that the idea of mastering the violin is completely in the way of this. So when they have been performed in the 50s, 60s, 70s, all I know from hearing is very difficult, because everything is so complicated, and so trying to find some violinistic solutions for something that is actually, you have to see what is the context, what is the dance at that time.

PAN M 360: So if I understand, through the years and the decades, the people that are mastering those pieces went closer to the original way to interpret it. This is what you mean?

Christian Tetzlaff: Yes, original is a difficult word, because we don’t know exactly how he played it, but we know a lot of things that did not exist, and many think that are so, in retrospect, so funny and not very smart to deal with it, making it very difficult, those fugues, whereas it’s so easy, because he had to write them in a certain way, but the notation is just the most easy one, and one always plays the melody line a bit longer, but what violinists always tried is to play all the chord full or break them in two and two, which in a piece that always talks about four independent voices, makes it unintelligible.

You cannot understand the simplicity of the beauty of the writing when violinistic you do such complicated thing, and then with constant vibrato, so then you don’t have the ability anymore to say this note I want to highlight and put a beautiful vibrato on it, and the kind of goings that were just measured. There was a time where it was seen as mathematical music and as square, and there is no music that is more alive and human and talking and especially playing by yourself.

It allows such freedom to explain the pieces and to make them easy to follow, and this all didn’t exist when people started picking them up in the 20th century. So we live in glorious times for this.

PAN M 36: And by the way we finally may not expect a recreation of what we think it was.

Christian Tetzlaff: Well, that I don’t know, because for instance I play on a modern violin, so the sound it does not match, but what he wants to express, what he wants to express, I think, is informed by how it was played and how his cantatas were played, and he’s not all of a sudden a different composer who forgets about everything when he writes for the solo violin. It’s the same music, the same expressive big music, and we now find ways of making it alive in a different way. Yeah, do you sometimes play it on a baroque instrument? I did a bit, but I find the fascinating thing is with Bach that you can hear a fugue for the piano played by a saxophone quartet, and it sounds totally wonderful if they phrase and understand the music, and it is very touching.

He is slightly beyond the instrumentarium, but it still means you have to have the information how it was played so that you get most out of it.

PAN M 360: Also it must be a great challenge physically, I suppose, to play all those pieces in the same program.

Christian Tetzlaff: Yeah, it is. But that also has two sides. Usually I come into some kind of trance if I play a while and in communication with the audience, and then all of a sudden these pains or these challenges, they go less in a beautiful way.

PAN M 360: A sort of communion adrenaline that makes the pain disappear.

Christian Tetzlaff: Yes!