Additional Information

Forty years ago, Quebec composer Claude Vivier passed away, leaving behind him a body of work as fascinating as it was unheard of, whose lasting influence is still palpable in the music of our creators today. Held from March 7-17, 2023, the Semaine du Neuf, an event organized by Le Vivier, which is in its first edition this year, will pay tribute to this giant of Quebec music through a series of concerts dedicated to part of his production.

On Tuesday, March 14, 2023, it will be the Temps Fort Choir’s turn to take the stage at the Monument National to present Journal, a monumental composition with dizzying technical demands, rarely performed in public, and whose last performance in Montreal dates back to 2009.

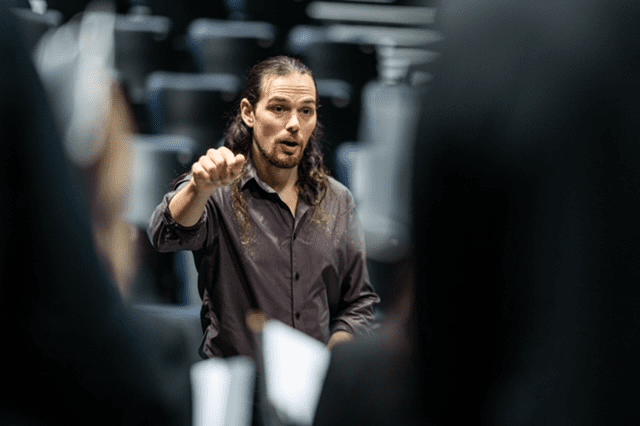

PAN M 360 spoke with Pascal Germain-Bérardi, artistic director of this emerging ensemble, to learn more about the process that led to the existence of this project, the challenges of performing such a piece, and what the conductor and his group have learned from it.

PAN M 360: The Temps Fort Choir, of which you are the artistic director, is a growing musical ensemble. How did you come to be asked to perform Claude Vivier’s Journal for the Semaine du Neuf?

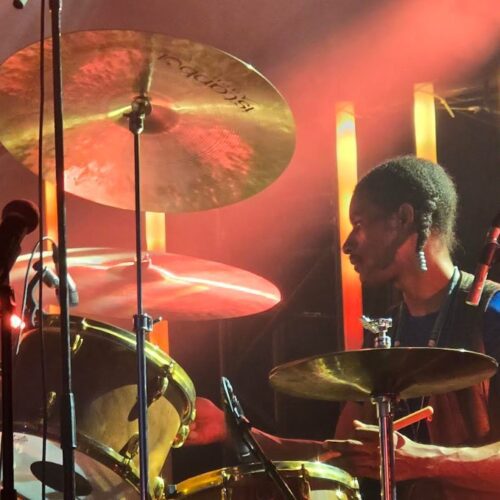

PASCAL GERMAIN-BÉRARDI: This project was initiated by percussionist David Therrien Brongo. He and I already knew each other, as we were in the same metal band in the past. David is studying the music of many Quebec composers as part of his PhD. So he was aware of the fact that Journal had been performed here very little in Quebec. He also knew that I run a choir and that I like to do things that are off the beaten path—it is this aspect of our practice that has established the choir’s reputation and given us credibility with granting agencies. As we celebrate the 40th anniversary of Claude Vivier’s death this year, it seemed like the perfect time to tackle this ambitious program.

PAN M 360: Journal is a highly virtuosic piece where many forces come into play, both in terms of textures and sound planes. How does a conductor reconcile these technical challenges with the inherent intimacy of the work?

PASCAL GERMAIN-BÉRARDI: As soon as I laid eyes on the score, I knew immediately that this was the most difficult work I had ever conducted. And yet I have conducted Stravinsky, Bartók and Penderecki during my university career! Several members of the choir and soloists have expressed similar opinions. We had to rehearse for a total of 35 hours to achieve our goal, which is much more than for a standard classical music concert, where the average is around 9 to 12 hours. But the difficulties are such that it was necessary to make this extra effort.

The first step in my work with the singers was to isolate the most complex parts of the work. This involved a lot of rhythmic solfeggio, on the one hand, but also a thorough analysis of each of the chords stated in the piece so that each performer could appreciate its distinctive colours. This step was particularly long and arduous. When one plays an instrument like the piano, the accuracy of the sound is not a concern in itself. You just have to press the key to hear the associated note. In singing, this is not possible. It is therefore necessary to integrate the chords one by one in their respective context in order to better feel them and to attack them with confidence during the performance. Fortunately, Vivier’s harmonic language is very intelligible. I also allowed the singers to bring a tuning fork on stage for him to use in case of insecurity. This is not something I usually do, but in the context of a concert, it seemed justified, if only to ensure the well-being of everyone.

PAN M 360: This desire to think outside the box is one of the first things one reads about your ensemble on its website. There are also references to the desire to share powerful moments, the excitement of the ritual of passage, the miracle of a performance, and even music as a survival instinct. In short: a visceral experience.

PASCAL GERMAIN-BÉRARDI: Yes, my relationship to music is visceral, whether we’re talking about metal or punk rock, but that’s true for any style where there’s a very strong energy. Classical music is no exception to this type of intensity—think of Beethoven’s ability to break down walls and conventions, Bruckner’s grandiose, almost cosmic music, the death metal nature of some of Shostakovich’s works, or the tribal nature of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. The concert is for me a privileged moment to share the fruit of our work with the public. It gives us the opportunity to broaden their horizons, to make them experience strong emotions, to teach them something about themselves and to elevate them while giving them a good time. These aspects are fundamental to me and guide every thought I have before producing a concert.

In the case of Journal it is a little different, because its intensity is found less in the raw energy that emanates from it than in the depth of the affects from which Vivier draws his inspiration. The work is divided into four sections: childhood, love, death and after death. Each of these sections is filled with moments of fragility. The love sequence, for example, explores the abandonment of one’s first great love, that moment when one is convinced that one has found in the other the part that completes one. It also deals with the feeling of love that is confused with sexual attraction, the countless questions that its pursuit can generate, as well as the whirlwind of panic that can take hold of us when it suddenly leaves us and we feel as if we have lost it forever.

Human reflection often takes the form of thoughts that unfold simultaneously on different planes. Then, without warning, a fixed and latent idea comes to take all the place, the space of an instant, then declines in a new tree of ideas. Vivier, I believe, translates well this tumultuous cerebral activity. It is the accumulation of these layers and the way they are treated that gives the work its great intensity. It is also in this sense that I approached my work with the singers. Once the technical challenges were overcome, I focused on the meaning and scope of these affects, and on the way they are embodied in the score. Sometimes a piano subito can mean more than just a gentle dynamic. It can also be a symbol of complete uncertainty.

PAN M 360: After all those hours spent working hard to give shape to these complex ideas and crossing the line between life and death a thousand times over through Vivier’s work: what have you learned and how has the group grown from it?

PASCAL GERMAIN-BÉRARDI: Some of the singers have told me that their rhythmic solfeggio is now going to “wipe” (laughs). Others have mentioned that the complexity of Journal has allowed them to put into perspective certain works of the repertoire to which they have been exposed. They also feel a great deal of pride in being part of such a special event. But more than that, there is a strong sense of accomplishment. And that’s something I look for in my projects and value greatly.