Additional Information

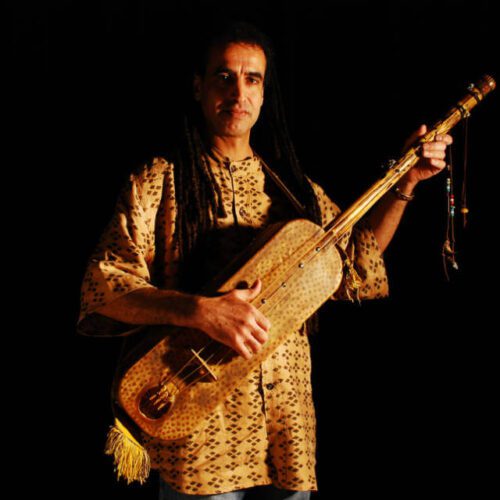

Photo: Lucas Paris

Both a composer and visual artist, the Quebec artist designs and builds interactive objects that react to the movement of the user in real time. In this case, himself. Hypercube is the most recent of these objects, once again coming to life in front of an audience, or on your screen.

Langevin-Tétrault is behind the conceptualization or co-design of various projects appearing internationally – Interferences, Falaises, DATANOISE, QUADr, ILEA, BetaFeed, Alexeï Kawolski, Recepteurz, and of course Hypercube, presented this Wednesday at MUTEK Montreal.

The works of this Baie-Comeau-born artist constitute ecosystems involving audiovisual devices based on cutting-edge digital technologies, but also on both physical and theatrical interpretation.

Why does an electronic music composer choose to become multi-disciplinary?

“I studied digital audio composition at the Université de Montréal,” says Langevin-Tétrault. “Before going into these studies, I was a guitarist and keyboardist in rock bands, I had a relationship with the stage. I really enjoyed learning how to compose, but I missed that connection to the stage. I like the exchange of energy that happens only when an audience is in front of you. But I found it difficult to recreate this energy by manipulating only a computer on stage. I missed being able to move, to use the whole space. I wanted movement on stage to be part of the performance.”

He’s been working on this project for the last six years.

“I try to create devices that allow me to interpret in real time. Electroacoustic instruments don’t exist, or are very rare, they’re usually controllers with buttons. So I decided to interpret through gestures, and therefore through a physical relationship with audiovisual objects whose sound and light I control in real time.

“I used to broadcast my music on the Internet,” he says. “I used to make electronic music where I was inspired by both experimental codes and more popular electronic music. In the studio, I worked a lot with modular synthesizers, a kind of continuity of the IDM trend – an expression I don’t like that much…”

Langevin-Tétrault interacts with devices that, he says, have a personality of their own – well, almost.

“This performance is the result of my relationship with the device that manifests an appearance of behaviour. I am not the only one doing the show. Hypercube seeks a balance between planned performance and moments of free improvisation. It is important for me to have this freedom to improvise. At the same time, I don’t want it to get too confusing. I still have a direction during the performance; different predetermined signals or points keep me on track. It’s important that there is a coherent dramatic arc. I’m free to do what I want to do, but I try not to get lost in the performance.”

Langevin-Tétrault is aware of the risk of working with state-of-the-art digital audio equipment, because there is always the trap of technical prowess… not necessarily at the service of a conclusive work.

“I worked in the studio for a long time to make sure that it sounds good, that you can listen without seeing and be satisfied with the audio. The idea is not to make a kind of big buffet and demonstrate the full potential of the object, but to stay within the same aesthetic and present a coherent work from beginning to end. Technology is a tool, not an end in itself. The objective is to express something.”

Langevin-Tétrault notes that advances in computer technology and access to laptops that have become very powerful are driving this advance in artistic expression.

“Not so long ago, the possibilities of real-time interpretation were limited, computers did not have the same capacity. Now, if you have any programming skills at all, you can do quite complex things in real time. At the end of the day, it’s not so much technology as imagination and mastery of the tools that prevail.”

In the case at hand? The designer of Hypercube explains.

“To create the device, I was inspired by the idea of a geometric form that moves in time, in the fourth dimension. When I manipulate this shape, I get a lot of simultaneous information from sensors – it allows me to deduce the orientation and position of the cube. In addition, the tension sensors linked to the cables that keep the cube in suspension allow me to control the music and the light. I must mention here the contributions of Lucas Paris, who helped me a lot in the construction and programming of the device. He’s to me a valuable collaborator, an artist himself. He has a great passion for electronics, he excels in programming, he knows how to find the right components.”

Contrary to the more physical aspacts that have characterized his previous performances, Hypercube takes the artist elsewhere.

“It’s more nuanced, more subtle, in restraint, in nuance, in introspection. It requires me to move, but in a different dynamic, because the slightest small movement has an impact on the sound. I have to be really concentrated to succeed in this performance, it can be close to tai chi or meditation. I’m exploring another emotional zone here – very slow movements, deep breathing, more vulnerability on stage, I try to make it look as simple as possible. In my previous performances, my posture resembled that of a rock guitarist. This time, I try to avoid my show-off side. In order to make my gestures evolve, I worked with dancer and choreographer Anne Thériault, who followed me throughout the process.”

Such interactive devices are certainly attractive when their creators use them wisely, but… when they move on to the next chapter, do they have to constantly relearn a new language without having really mastered the previous one?

“It’s a lot of work to reinvent every time. At the same time, the more you work with technological tools and the better you understand how to work with them, the easier it gets. So the aesthetics have become clearer over the last few years, there is less wandering, I know much better where I’m going.”

For Langevin-Tétrault, the artistic success of his Hypercube lies above all in its ability to harness the technological beast and put it at the service of the work.

“In recent years,” he notes, “we’ve seen more and more artists who can transcend the tool. You can appreciate the work without knowing exactly how it was conceived… that’s not what matters. So there’s a greater emotional charge than before in audiovisual works, it’s less cerebral, less hermetic. The audience is able to grasp what it is about, rather than how it is done.”