Friday night at Eastern Bloc was an evening of joyful, playful practices that invoke the child and the emotions of the heart. From the heart came voices, powerful and defiant in their poise, that spoke and sang of stories. Stories about passion, about the clouds and the coming rain. Practical myths for a pleasurable life, extending far beyond the stage. How can we carry them there?

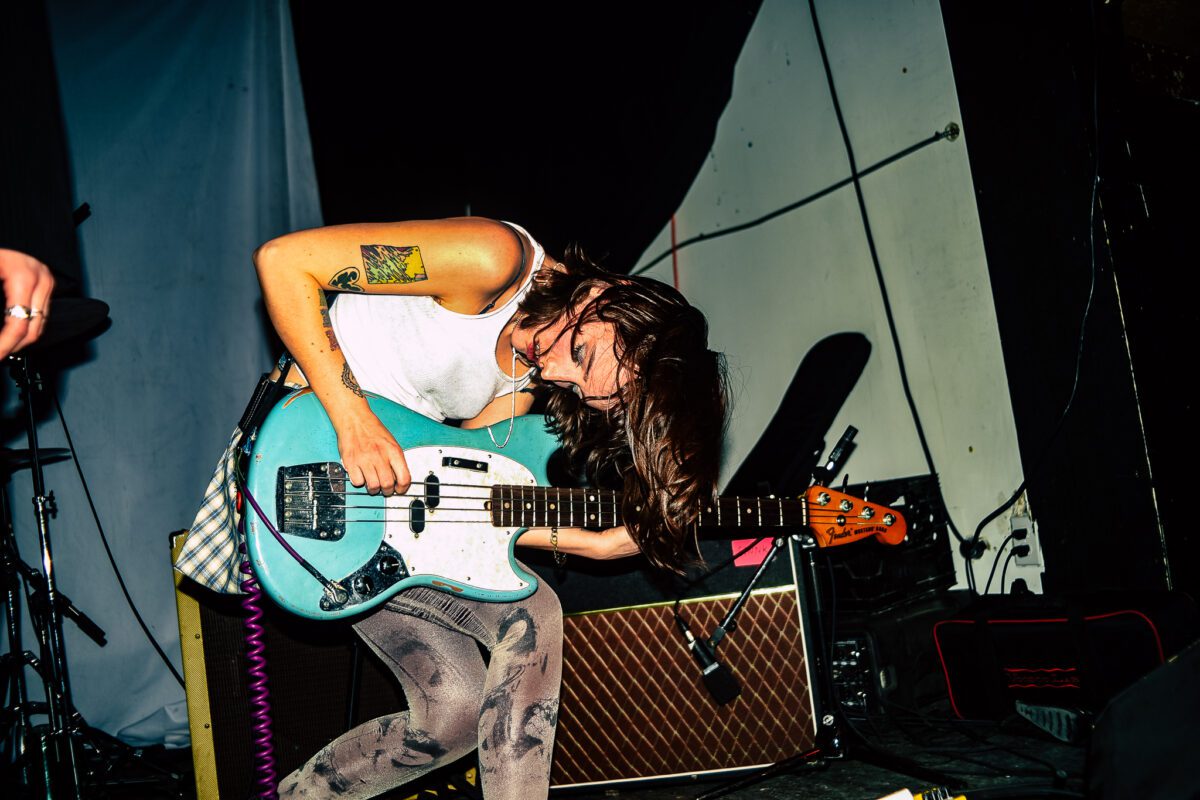

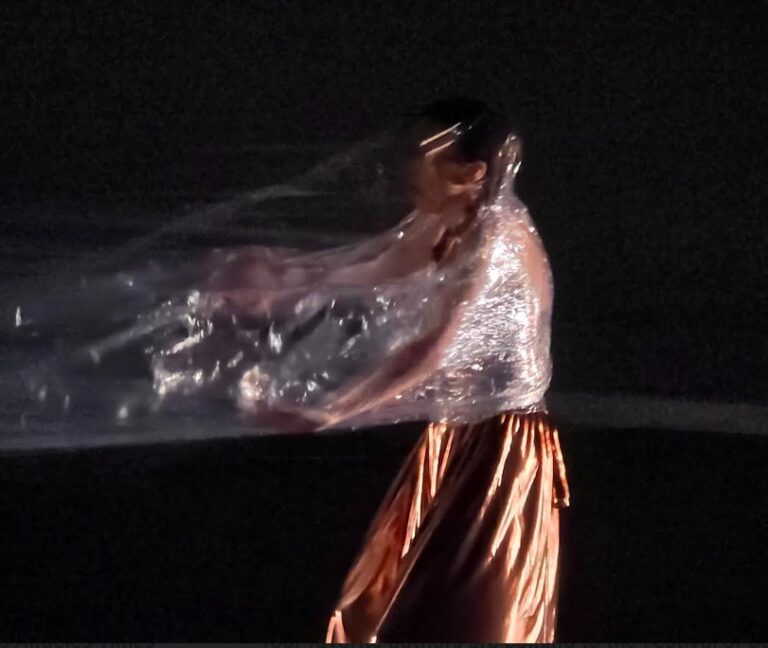

Fili Gibbons accompanied by their fairies dissolved all boundaries between public and performer. The sounds blanketed a stream of casually recorded discussions between the artists and held a space for introspective thinking. Occasionally, this space would open up and invite the audience to share their own thoughts. « What is happiness to you ? »

Between themselves the artists smiled and laughed as they arranged an eclectic post-digital garden of love. At moments, Fili’s voice seemed a conduct of light that opened a portal to ancient folk traditions. A kind of symphonie of spring, the melodies played on themes that could have been heard in a Ryuichi Sakamoto score and their cello held a similar mystical depth to Arthur Russel’s as it weaved itself into an electronic ambiance.

While the visuals held a line of continuity in their colorful and glitchy textures, the performance segmented itself into a series of short poems and scenes. Friendship, love, passion, work, fatigue. Each theme held itself in an intimacy that made the subjects honest and approachable, nothing was left out or hidden from the audience. From the last time I saw Fili at PHI Centre, their sound practice has evolved towards further use of sampling and looping still with the same calm and sensitive style. Definitely an artist to look out for and I am excited to know what they do next.

Overall I was very impressed by the care that Sight+Sound put into curating a showcase around, well, care. Underlying elements of astral connection and myths of love tied together the pieces from Fili Gibbons to Deep Gazing.

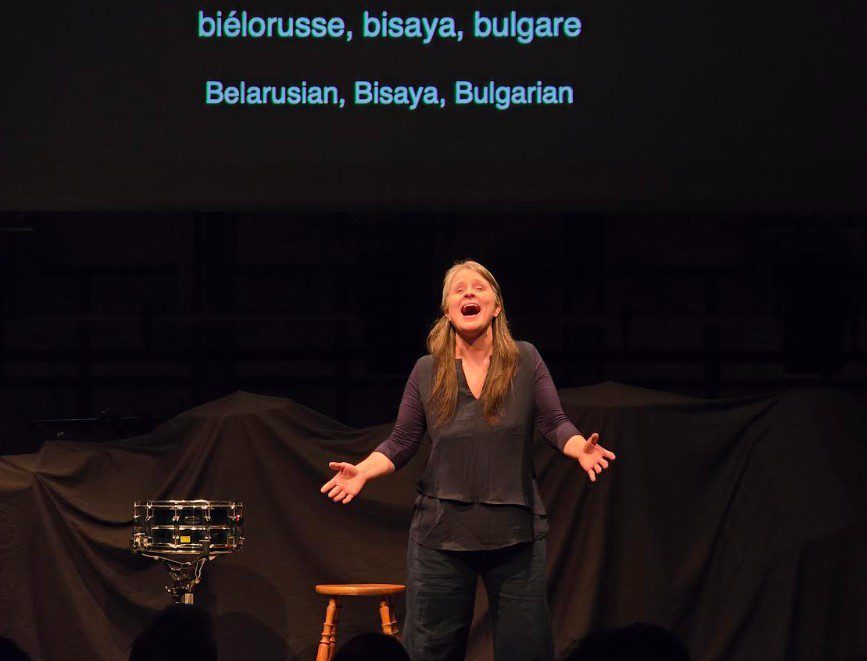

This last performance had the crowd smiling all the way through as the over-exaggerated characters gazed longingly at each other in the eyes. The Sisters of the Celestial Order held the crowd in their spell as they read through their book on a new practice called « deep gazing ». Quite literally like listening to mystics, they slowly and carefully explained the shape of clouds in humorous and poetic fashion.

Their philosophy slowly seeped into our imaginations as we left and looked at the sky « Skry! ». Sight and Sound is a reminder of the importance of art in our lives, it is what leaves you full and accomplished at the end of the day.