Additional Information

Truck Violence is a band with an enigmatic but emphatic agenda. Equally aggressive and sombre, enraged but mournful, the heavy, neck-breaking breathlessness of Truck Violence can be summed up as a series of captivating dualities. The inherent human desire to be remembered is counterbalanced by the innate need to shrink away and die when the sunlight touches you.

In conversation with the band’s singer/screamer/poet Karsyn Henderson, you get a sense of the tumultuous innards that are so proudly eviscerated upon Violence, their debut LP. In the wake of so much change—a catastrophic house fire, changes to the band, and a clean slate removal of the group’s prior catalogue, just to name a few—we understand that this is an era of brutal and all-encompassing transition, for both the band and the person at its centre. Like setting the whole forest ablaze in the hopes of welcoming new growth, we see now the very foundations of Truck Violence laid bare.

Eloquent yet direct, Henderson’s bloody fingerprints are all over the themes and sonic stylings of the album, an ode and a curse to his roots of small-town Alberta and all the damage it did to him. Far beyond a collection of hardcore, sludgy, folksy tracks—Violence is an auditory exploration of trauma, memory, and running away from home, only to find yourself right back where you started.

PAN M 360: First off, I want to congratulate you on all the hype surrounding Violence. How has the energy around the project felt as you approach release day?

Karsyn Henderson: I’m a bit of a recluse, so I’m kind of shielded from it. I always have a great deal of dread when it comes to releasing things. So I’m never actually all that excited about it. I kind of always assume that it’s going to do poorly. I think as an artist, until you’ve attained some level of success—and the success, in and of itself, is a horribly malleable thing—it’s hard to ever feel like anything’s gonna go well.

And then you get thrust into this slog of ‘What is doing well?’ and ‘Have I done well already, and I just can’t see?’ I don’t know, maybe some people think we’ve been doing well. You can never tell, I guess. Expectations are always, like I said, a horribly malleable thing. I’m just throwing my hands up in the air like a bag in capricious winds. And wherever I go, I guess I’ll go there.

PAN M 360: There’s been a more deliberate and DIY feel to the last few gigs with the free, outdoor vibes and the monthly shows. Have those felt very different from venue gigs you’ve done in the past?

KH: Yeah. First of all, I’m so ecstatic every time we play a show and there are people there. I feel like every time people show up, it’s out of coincidence and they just happened to be in the area. Something that’s troubled me a lot in the past with playing venues is that there becomes this divide, right? There’s an audience who is there to look at a stage that they’ve seen plenty of other artists share in the past. I’m watching somebody who has practiced a song, practice it again, except showcasing it towards me. That’s not to say that venues aren’t good, or really valuable and important to the growth of the scene. But every time you play in a random patch of grass by a highway, that is the show by the patch of grass by the highway. It’s the only time you’re ever gonna see it.

I think it breaks down that barrier. Have you ever been on the metro, and something fucking crazy happens? And then all of a sudden, the partition—that thick woolen curtain—is lifted. Everyone looks up and you finally see each other. And you can say something to each other. We’re all here, and we all just saw some crazy shit happen. It’s that same feeling. All of a sudden, everybody is super down to be genuine.

PAN M 360: With that in mind, has this felt like a period of transition for the band?

KH: Oh yeah. Our house just burned down, and so that’s adding extra weight on top of the upheaval. It’s sort of a strange feeling to put something out there. Because you’re essentially letting go of a part of yourself. And then in conjunction with that fact, I’ve lost everything that I had already. So it feels like I’m essentially losing everything in one fell swoop. It really sucks in the moment, but I think it’s ultimately beneficial. I think it’s a good thing to lose everything once in a while if you can afford to do it.

PAN M 360: Touching on the fire, obviously there’s no good time for something like that to happen. It’s horrible, and thankfully no one was hurt. But has it led to any revelations on things you’re grateful for after losing so much?

KH: Sort of. I suppose ‘grateful’ is a funny word, but in some ways, yeah. I think when you strip yourself down to the barest of points, where you lose routine, you lose material comforts, if you are isolated from any companions or physical supports, I think it’s a magnifying glass. It’s been an exacerbating force that has led me to want to better myself in a lot of different ways. And I think it’s also taught me that I can exist without a lot of different things. And I guess that’s always a nice thing to know, that, I guess if you lose more in the future, you know you don’t just cease to exist. You just move on. Whether that’s a crushing thing, or whether that’s a motivating thing, is sort of up to you. Sometimes it’s nice to know how much it takes to really get you over the edge. It can be nice to know where your breaking points are.

PAN M 360: I suppose that ties into the themes of the album as well, exploring that breaking point, exploring resilience, exploring what that means for you. Did you make any connections like that as you went through this experience?

KH: I suppose so. People love to narrativize. That’s all we do all day, all night: Narrativize things to fit them into these compartments. My first thought when I got word that everything went up in flames was, “Alright, I guess that makes sense.” Like, it’s consistent, at least, that these things will continue to happen. I guess I wasn’t even surprised by it, and I was a bit nonchalant. I feel like I’m always waiting for things to change. And often they don’t—they just change form, but remain consistent. And so yeah, I mean, in some ways, the fire just feels like a return to normalcy.

PAN M 360: I hate to suggest commodifying such a horrible thing just because it feels easy. But doesn’t it feel weirdly poetic for this to happen now, of all times?

KH: I would never be afraid to commodify things. Everything’s commodified already. You can only do so much extra damage, right? Everything is trying to fulfill a pretense that you have in trying to sell things. This whole album rollout and everything else is meticulously crafted to sell that idea. And you could swap out the word “sell” for “paint a picture”. But at the end of the day, the way that the music industry works, it’s all about being a salesperson. And if this tragedy works to my benefit, and makes things seem more real, then why not?

PAN M 360: Getting back to the album, you’ve made no secret that Truck is meant to be heard live. Was it hard to capture that on the recording?

KH: Yeah, definitely. It’s our first time recording music like this, besides a shitty death metal album when we were 16. But if it’s something that is meant to be heard live, it’s something that still sounds interesting and cool in its own way on the recording. I guess now that I’m done with it, I’m always like, OK, well, I want to do things over again.” But I am more than happy with how it sounds recorded, and it’s always difficult to capture that. I owe a lot of my intensity to intangible things that you can’t see through your Spotify.

PAN M 360: How did you arrive at the sound of Violence from Hinterlands and your other previous work?

KH: Age. Time, I suppose. I think Hinterlands was, in a lot of ways, just throwing yourself really far out and seeing what you can reel back. It was just a fun experiment. And I’ve had time, not a ton, but I’ve had time to mull over growing up where I did, and I’ve mellowed out on a lot of things that I was extremely spiteful about. And it felt right to return to something that is real and authentic.

I always had a nebulous image in my mind as to what I wanted it to sound like and what I wanted it to feel like. I think it’s always a feeling thing, more than it is an actual sonic thing. We didn’t go into it being like, “OK, well, we want to do hardcore with elements of folk and like, we’re a little bit sludgy.” We never had those conversations. It’s always “What do you want people to feel when they hear it?” I’m so glad that we arrived where we did. It was very difficult. And we lost a lot of what we had before. The community that we have now, compared to what we were doing with Hinterlands, it’s not even the same. We’re not even the same band anymore at this point. It’s gone through so many different permutations. And, I mean, they’re all good, I suppose, in their own ways. It was a big transition. But it’s one that I’m proud to have made.

PAN M 360: I wanted to ask about songwriting. You’ve said before that you believe music is the main vessel for poetry in the modern day.

KH: Oh yeah, absolutely. Poetry as an art is totally and utterly dead in the way that we understand it. Nobody reads poetry besides poets at this point. If the only people who consume your art are the people who make the art, what are we really doing here? Even though I would love to write books, you have to begrudgingly adapt. People want intense stimulation, and the only way to do that with a great deal of effect at this point is to do it through music.

PAN M 360: How do you approach creating music around these dense, jagged lyrics? What does the process look like to create a Truck song from page to stage?

KH: It’s always two things at once. Usually, the music is being created as I’m writing on my own, and we’re all in the room together. And a song might pick out a poem I’ve written before, and it feels like, “Okay, this makes sense.” I find it super funny that Paul [Lecours, guitar] is what I would call essentially our main songwriter. He’s like, the least poetic person I’ve ever met in my life. He doesn’t say anything with any art. When you think of jean jacket dads in the countryside who don’t say anything unless they need to say it, and they’re just sort of… coughing? That’s him. And the way that he talks about writing guitar—he has nothing interesting to say about it. Most people—like myself—can go on for hours talking about all the different processes. I love talking about it because everyone’s self-obsessed in that way.

I think Paul’s writing is so atypical because it almost feels like he’s woodworking or like… building a table sometimes. And the table doesn’t make any sense. And no one’s ever gonna use it as a table, because there’s not the right amount of legs, and it shakes and everyone hates it. But you know, he’s gonna build it anyway. Because that’s just how he builds tables. And I just like the way that he works. I’ve always admired that.

PAN M 360: Reading and listening to the lyrics, it seems that so much of it is borne from memory. Does that feel accurate?

KH: Yeah. I have really intense ADHD, and I am just utterly awful at staying consistently on a topic. And so that comes across in everything that I do, especially the way that I write. I think of it as a collection of symbols that come together to paint a picture through sense. This isn’t a science textbook, you know. So the best I can do is have these splits of image, and every flip recontextualizes the last until hopefully—and it doesn’t always work out—you get to this specific feeling that I was trying to get across.

And so that’s why it’s often really confusing. I think a lot of people don’t know how to read poetry, or they do know but don’t have the confidence to believe that they know. I think these people are sort of confused because it feels like a jumbling of different images. And how do you devise that? You sort of just have to believe that you can do it and take away what you can from it.

PAN M 360: Does playing these songs ever feel like a return to the places they’re inspired by? To small-town Alberta and everywhere else?

KH: I went through a lot of strange things growing up. And I haven’t had a lot of time to contextualize them and understand them. The terrible, but also the great thing about memory is that it is constantly changing. And so in certain ways, I never feel like I’ll get an accurate understanding of what happened when I was younger. I will just have these you know, colours and whispers and flips that I can sort of cling to when I feel them. I hope that they’re accurate to what I need them to be—and so I do feel it very intensely.

On the most recent run of shows, it’s been very difficult to not tear up while I’m performing. I mean, it’s a strange feeling because I don’t talk to anybody about these things. And then when I go on to stage it feels like it can just say about anything. I’ll just talk about these things that I’ve never told anybody in my life to a group of strangers. And I think that that’s a very cathartic, scary, and emotional feeling.

PAN M 360: Does that tend to feel more cathartic or painful?

KH: I feel like if you’re gonna make something great, you’re gonna feel awful about it. And I’m not gonna sit here and say I’ve made something great, but I do feel awful about it. So at least half of that equation has been met. It’s a very emotional experience, but I wouldn’t want it any other way. And I think that because of that, you can sense the genuineness at those concerts. Spend any time in the punk community in Montreal, and you’ll learn that principles aren’t anything and authenticity isn’t worth a damn. Just the shit I’ve seen. I guess that’s a big reason why I’m a bit of a recluse. I mean, people will just sell themselves for the least bit of ease. And it always makes me very sad. And I want to foster an environment where that’s not the case.

PAN M 360: What kind of preparation do you need to get up there and bare your soul like that?

KH: Oh, there’s no real preparation. I suppose you just sort of get up and do it. The biggest thing I’ve learned is to lower my inhibitions and to just not worry—throw everything to the wind in that moment. I don’t want to be attractive. I don’t want to be alluring, or mysterious. I don’t want to be any of those things. Because none of them matter. When I’m on stage, I make a lot of ugly faces. I don’t look the way that I want to appear. I make mistakes, and everything is imperfect. And everything is scary. It just sort of is what it is, and it happens as it does relative to my own temperament in that moment. I want everyone to look at this almost like you would look at a car crash. Like, “Holy shit. That’s awful. But it’s awful in a way that I understand.”

PAN M 360: Can you talk about where some of the images on “He ended the bender hanging” come from?

KH: The main focus is feeling like you’re a step away from where you want to be. There are doors around you that are closing before you can reach them. That’s a feeling that I’ve constantly felt. If you’ve ever been in a depression, you sort of yearn for this big epiphany moment: “Tomorrow, I’m gonna wake up and something’s gonna happen, and I’m gonna have all the courage, and all the confidence, and everything’s just going to be right,” And then every time it’s about to happen, it just doesn’t materialize in that way. Life gets in the way and the door closes and locks, and you feel like you can’t open it, even though you could probably kick that door down.

I come from people who didn’t have a lot of opportunities. And when they missed out on those opportunities, whether it was because of pregnancy, or depression, or lack of finances, they just never, ever rekindled it. Never captured it. And it just always felt like they had that moment, and it’s gone now.

PAN M 360: I’m struck by the vulnerability of “I bore you now bear for me.” Can you tell me who this song is about? What you were thinking when you wrote those words?

KH: I was writing it at a time when I was coming to grips with what it means to be a man, what it means to be vulnerable, and how that works within the cultural framework. I was also just starting to see my partner and starting to visualize all the different partitions and barriers and lament them. Because it would just feel so gratifying and so beautiful to be completely naked. I feel like I’m never naked.

PAN M 360: “Along the ditch till town” is a hell of a closer—who is this song for?

KH: I suppose it’s for people who find themselves in the same predicament that I did: Young kids thrust into awful situations, and it feels like there’s no way to get out of them. And for the slower realization that you, specifically, are in a bad situation. I think when you’re younger, you don’t even realize sometimes how bad things are until you’re able to contextualize them. So the track has a little bit of an innocent tinge to it.

PAN M 360: Did you ever run away from home as a kid?

KH: Yeah, a couple times. Tried to. But you’re in the countryside. Where the fuck do you run? Like, a highway? I tried to run to wherever I could, but in the end, you’d always just find your way back.

PAN M 360: The opening track is a pretty earnest admission of the thought you give to your legacy, your presence, and your perception. What do you hope this album and all the press will do for yourself and the band?

KH: This album is nobody’s masterpiece. We’re all just trying to figure things out. And this expression is deeply earnest. And I hope 10 years from now, I’m gonna look at it and say I could have done such a better job. But at least everything was truthful. Everything was honest. Everything was earnest. And there was no patchwork. There was no censor. There was no tampering. Exactly what we could do is what we did. And that’s all I want it to be. It’s a first foray into something new. And it’s extremely dear to my heart, even now, I know it’ll grow dearer with time. But the song about legacy really is more local than the song made it out to be.

I think about how I’ll be remembered by my family. And when I talk about writing and being written about it’s not grandiose. I write things about the people that I love. And I love something as simple as getting a note written to me. And those things are what I count as legacy today.

In this moment, we’re both very cognizant of how [this interview] is gonna come across to people who aren’t even in the room. How’s somebody who has no idea what either of us are doing going to interpret this? It always feels infinitely less personal.

It’s good and it’s important in some ways to connect with other people. You have to broaden your scope. I think it’s a beautiful thought that somebody else might read this interview and take something out of it. I think that’s a great thing. But it doesn’t hold as much water as hearing my mom telling me that she likes one of the songs.

PAN M 360: What does your mom think about your music?

KH: I don’t know. I really don’t know. I’m sure she’s just happy that I’m doing it, and I think she’s glad that I’m not doing drugs on some punk music hard shit in the big city.

PAN M 360: I showed my mom a video of you guys playing. She said you sounded like the orcs from Lord of the Rings.

KH: You know, I get it. I’ll take that. Peter Jackson, if you’re reading this… Yeah, reach out.

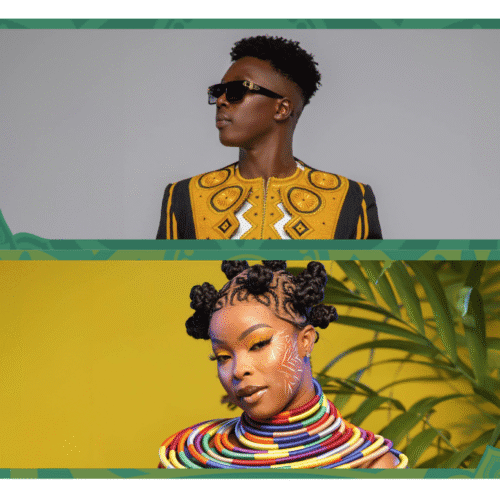

Photos by SCUM