Additional Information

With two albums, 1979’s Y and 1980’s For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder, The Pop Group unknowingly laid the foundations of post-punk. Influenced by the anarchic and aggressive aspects of punk, but with their ears tuned much more towards funk, reggae and dub, the Bristol-based band influenced an impressive number of musicians in its short career, from The Birthday Party to Sonic Youth to Bauhaus, St. Vincent and of course the entire trip-hop cohort of the British port city.

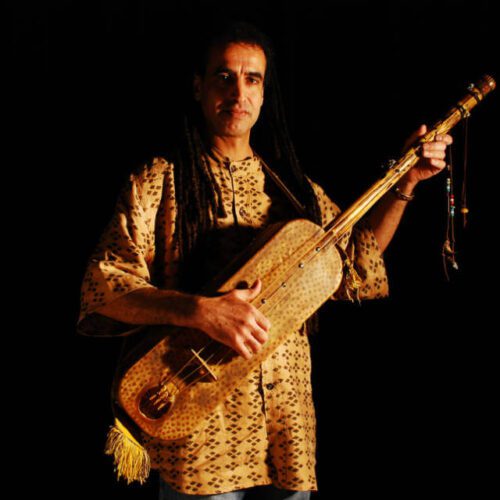

Just after Y’s 40th anniversary, The Pop Group, which reformed in 2010, called on visionary producer Dennis “Blackbeard” Bovell to resume his role at the helm and rebuild the dub version of the album he recorded with the band on a farm in the English countryside in 1979. Y in Dub is a collection of nine heavyweight dub versions reflecting the prodigious intensity of the source material, and the enterprising originality of the dub and reggae music that inspired The Pop Group.

With Y In Dub, The Pop Group and Bovell explore Y, amplifying the shadows and echoes, intensely accentuating the resonance of each element. The original material is submerged and sometimes extended, broken, shattered and sculpted into turbulent, contrasting forms that deviate from the original tracks in unpredictable ways. On this new oddity, Bovell, known for his numerous albums, the Babylon soundtrack and his work with Linton Kwesi Johnson, Fela Kuti, Madness, The Slits and many others, adds another inventive step to his illustrious career.

To tell us about this restless and confusing experimentation, we caught up with the band’s singer and lyricist Mark Stewart. A first-rate iconoclast, a gentle nutcase who’s very likeable but not always easy to follow, the man has an impressive track record, whether it’s with his band Mark Stewart & The Maffia or with the New Age Steppers, Tackhead and Adrian Sherwood’s On U Sound System crew.

PAN M 360: Why did you choose to do a dub version of Y and not For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder, for exemple?

Mark Stewart: I’ve always been very interested in dub techniques, you know, I kind of dub up my life. Dub for me, it’s the music of chance—you don’t know, when you suddenly turn off everything that’s underneath, what the bass drum is suddenly going to do on its own. It’s just such that it’s just such an interesting experiment, and time and time again. When I’m sitting with Adrian or sitting with Dennis Bovell, I just say, cut everything, and you’re on this cliff’s edge, then suddenly a violin floats in which you didn’t even realize was there. It’s really cathartic. And it’s unplanned. And it’s kind of like, there’s this thing in England called psychogeography, where you walk around the city, but you deliberately go left instead of right. And that whole procedure for me is kind of cleansing, time and time again. Because what happened was that suddenly we got the master tapes back and me and Gareth, we’re in our office, right, with this box and we open this box, and we’ve sold these tapes with our handwriting on it. We haven’t seen the tapes since 1978. Right? And I said to Gareth, I said we should dub it. Because we were using dub experiments and we were influenced by concrete music when we were making Y itself. But we said, get Dennis to dub it, but just use exactly what’s on the master tapes. Nothing fresh, no news or plugins or effects, as King Tubby or Dennis would have done it back in the day. Right? Obviously, it’s not a retro thing. For me, it was quite a heretical thing because that has become a… I don’t know, it’s become a sort of totem. And I thought it’s quite good to flip it.

PAN M 360: Tell me a bit about about Dennis Bovell. Why did you choose to work with with him in the first place for the original Y?

Mark Stewart: Right. So we were still in school and we were just playing these clubs. And then suddenly, these music editors of Melody Maker and NME started taking about us really seriously and doing these interviews with us. And I was, you know, I was out there anyway, I would have been out there even if I wasn’t in the band. I was reading Apollinaire and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And I thought I was some kind of intellectual. But suddenly, they start saying, ‘oh, this is so weird, it sounds like Captain Beefheart’. I didn’t really know who Captain Beefheart was. And reading all their theories… The Pop Group is a perfect thing for journalists to reuse their college essay as a review. So I was going to a lot of soundsystems and the late-night clubs in Bristol, which are basically reggae clubs or soundsystems or dub clubs, and I just loved scooped-out versions of the classic reggae and deejay [or toaster, not to be confused with DJ] tracks that were happening at the time: U Roy, I Roy, Aggrovators. I was immersed in reggae. Where my mom grew up is where all the Jamaicans came to live, you know, when they came on the Windrush. But in Bristol, we don’t really see colour. we’re just Bristolians, right? Anyway, so the label, we had a really cool guy, Andrew Lauder, who ran UA, who signed us up, right? And he was really open-minded. He was going, ‘well, who do you want to work with?’ And we said, we don’t really want to work with anybody. And he was going, ‘well, you know, people use producers’. And so we all said John Cale straightaway because of his work with Nico, and we loved Marble Index. And he’s worked with the Stooges. And it’s quite free jazzy, the arrangements of the sax and stuff… And so they flew John over and we had a meeting with him in our school during lunch break, and John kept on falling asleep. Perhaps he was jet-lagged or so, but we couldn’t understand what was going on. But then, because we were so much into rhythms and reggae and funk and the rhythm sections, we kept on saying we wanted to work with King Tubby, but then we found out King Tubby had been shot. And all the way from the age of 13 onwards, I was knocking off school a lot and I’d hang out, when it was raining, in this record shop called Revolver. Every Friday, when what we called “the van from Zion” arrived with that week’s prereleases from Jamaica, the little seven-inches, I’d just be in the other room saying, ‘play the version, play the version!’ Bought them all with my dinner money. I didn’t eat. And it turned out Adrian Sherwood was a delivery man driving the van down from London. But anyway, so there was one record that I was really into, like, just before we were having these meetings, and it was called “Feel Like Making Love”, by Elizabeth Archer and The Equators, but there was a version called “Feel Like Making Dub”, and it was slowed down and there were lightning crashes. It was full-on. You know, the dub I like is messianic. It’s just full-on and it sends a shiver. It’s like lightning! What do they say? The bassline is in your spine, or something? Anyway, that’s what gets me going, the full-on Biblical dub. And they said Dennis Bovell, and I knew Dennis was in Matumbi, because they were sort of playing around England at the time. And so I just said, see if this guy can do it. And we reached out to him and we had a meeting with him. And as soon as we met him, he’s just like, a big furry bear like somebody from Sesame Street. You know, I got this saying, don’t grow up–it’s a trap. I’m still in my kung-fu pajamas I’ve been wearing since I was 12, you know? And Dennis was just so playful and naive and excitable. So he gave us the excuse to be idiots. I’m not gonna call it art, but it’s all about play. When you play, you juxtapose, then stuff happens. He just encouraged us. And he was very playful. And suddenly we have like, 50 takes of this track called “Blood Money”. And there’s a track called “:338”, which was just like “Beyond Good and Evil” backwards, which has turned out really good on this dub album. It sounds like a sort of mad Neu track or something. Again, it’s just suddenly something which started off as a sort of one-two-three-four punk song or whatever, when we were kids doing “I Wanna Be Your Dog” or something, and it suddenly becomes something else. You know, there wasn’t a lot of thought into it. If you flip something or turn it backwards or open it up, suddenly, you’re in another universe.

PAN M 360: Did you want to steer away from the original album or stay close to it ?

Mark Stewart: I don’t go into these things with preconceptions. We believed some of the politics of punk were non-hierarchical. We don’t tell somebody what to do, we just harness whatever anybody’s doing and flip it again and try and crash that energy with some other energy. I don’t know how to explain it. We didn’t know what was going to happen. And that’s what I like, you go in somewhere, you come out the next day at 7 o’clock in the morning, and something else has happened. You’ve got to keep your third eye open, you know, throughout life.

PAN M 360: And during these dub sessions, was it only Dennis working on it, or were you also with the band?

Mark Stewart: Basically, Gareth was there a lot. I was involved kind of remotely and throwing curveballs on the phone into it and just making stupid jokes, you know? And we were going backwards and forwards, and strip it down and turn it off and summit whatever, and I got overruled, because I weighed upon loads of farmyard noises and stuff like all those Joe Gibbs ones when there’s like cockerels. I would have started toasting “Old MacDonald Had A Farm”!

What’s really interesting to me is turning stuff off and opening it up, especially being the lyricist. I was interested in cut-ups. going back to Brion Gysin. And my stuff is just like collections of bits I sort of crash together just because I’m excited about these lines or whatever. Some of the stuff I wrote when I was 13-14. I call it psychic archaeology, it’s about going back into those tapes. Philosophically, my younger self helped me last year and the year before with these kind of messages. These lines came through to me, which helped some quite heavy situations I was in or trying to deal with in my mind at the time, it’s quite weird.

PAN M 360: Did this dub exercise help you rediscover the album?

Mark Stewart: I rediscovered the energy, it was like a seance. I hate to word use the word ritual, but we sort of conjured something up, we kind of bottled an energy, we managed to get this energy onto ferric oxide, And Dennis with his way in dub was like rubbing Sinbad’s lamp, and the thing jumped out again, but it’s a different sort of golem. They asked me what his name is but I can’t even pronounce it. It’s really long. I think it’s friendly. What do you reckon?

PAN M 360: Do you think that the dub version sheds a new light on the album?

Mark Stewart: Yes. Well, for me, the genie that we bottled and the ideas that I had for it were frozen in the vault of the label. They shed a new light on the situation I was in last year. So the light beams from the past into the future. You know, my grandmother was a clairvoyant and my father was obsessed with the power of paranormal things. But I think that maybe these messages are coming from the future. Why are they constantly thinking it’s coming from the past, or dead people? Who knows where these things are coming from?

PAN M 360: Do you remember how Y was originally conceived? And recorded?

Mark Stewart: Totally, totally because we went to this really weird farm called Rich Farm. We worked in a barn for a month with Dennis. And it was a crazy, it was one of the first time I’d really kind of been away from home, apart from when I was in the Boy Scouts, for such a long period of time, and we just had such a laugh. Staying up all night, coming across in the snow in our pajamas, you know, we were out of anybody’s control. Feral, absolutely feral. I mean, The Slits went there about two years later because we started helping The Slits, and we were touring and working with them, really, and they got Dennis to produce them as well later on. They did Cut there and you can see the effect it had on them on the cover of the Slits album, it got them naked, covered in what looks like manure.

PAN M 360: I read that you were influenced by much more than music at the start of the band.

Mark Stewart: Totally. The funny thing is movies were very influential on us. And then Patti Smith took us on tour with her when we were making this record, the original Y. And her piano player was called Richard “Death in Venice” Sohl. People don’t realize films were as influential as music, you know? And the thing is, when punk rock was kicking off, you could only wear mad clothes to these kind of art-centre bars. There were two art centres, a place called Dr. Finney and another one called the Actual Art Center. And it was the only place that people didn’t want to pick a fight with you. You know, you could go and wear your rubber fireman’s trousers you bought in the army surplus shop. Clothes are the most important, obviously, speaking to a unified gentleman of leisure like yourself.

PAN M 360: Ha ha! I used to be into that stuff. And at one point I said to myself, what’s this uniform I’m wearing?

Mark Stewart: Well, that was the point of the Pop Group. Because our best friends were in a local punk band called The Cortinas, and we were going up to this punk club where everybody played called The Roxy, up in London. And we just said to each other, let’s form a band. But punk was already not punk. We thought punk was about experimenting and challenging things, but it became… It was weird. It was kind of like pub rock. I mean, there was attitude, but it became traditional very, very quick.

PAN M 360: It somehow morphed into the no wave thing. And that was more interesting and more, I don’t know… adventurous?

Mark Stewart: My timeline is not the same. I was always listening to funk, originally, and then reggae, going out clubbing and stuff in Bristol, right. I never said we were a genre or anything, but we went straight from school to New York. You know, when we were playing Y, and we were there, us and the Gang of Four. We were the flavour of New York. And I was in New York weeks and weeks on end. And I was in these clubs next to Keith Haring, you know, it’s just mad. And the way that no wave kicked off in New York, we weren’t aware, really. I mean, we knew about Patti Smith, but to suddenly find out about James Chance and stuff like that was weird. We were playing these clubs, you know, we were so young. Seventeen, man.

PAN M 360: It’s crazy how influential the band became. I delved into Y, an album that I haven’t listened in a while, and I was struck by how much The Birthday Party was influenced by the band.

Mark Stewart: Yeah, Nick [Cave] says that. I don’t like talking about that, you know… It’s a circle… who was influencing your influence? We were totally influenced by like Ornette Coleman, and seeing free jazz guys like Derek Bailey and stuff. For us, it’s anybody that goes into the wilderness or makes an outsider decision to try and take a risk and challenge themselves first. We had this whole thing about deconditioning ourselves and questioning what we were doing, and the process of making Y with Dennis and Rich Farm Studios, of which Y in Dub is the process continuing. For me, it’s very difficult to sum stuff up and I don’t understand why one record means something and another record means something else. You know, another record I made, As The Veneer of Democracy Starts To Fade, may have kickstarted industrial music, I don’t know. Who knows? I get ideas from like mad R&B, the experiments they’re doing with tuning down kick drums and stuff, or like crunk, all that chop-and-screw stuff, you know?

PAN M 360: The band regrouped in 2010. You did two new albums, Citizen Zombie in 2015 and Honeymoon On Mars the year after. Is there any new stuff coming up?

Mark Stewart: Yeah, we’re still going. And we’ve just done Y In Dub live. Terry Hall from the Specials asked us to do something. He was in charge of Coventry City of Culture. Really, really interesting experiment. Because in the rehearsals, we were cutting the track, we were playing every third beat. It was really, really weird. It was like going through some sort of Marines training or something, stopping yourself from playing bits of your own soul. It was quite a heavy thing. You know, like when drummers tie one arm on to their leg to try become more ambidextrous. Can you imagine the songs you’ve played often and that you know intrinsically, and you have to just go ching instead of ching, ching, ching. It was really interesting. So Dennis had space to dub live.

PAN M 360: So are you thinking of doing that again?

Mark Stewart: Yeah! It was a very, very interesting experiment for us. I didn’t know what was going to happen. Again, it’s a it’s a kind of deconditioning you know, it’s a cleansing thing. I found it very, very interesting. I can’t compare it to anything. But it was it was really, really quite weird.

PAN M 360: Are the songs “It’s Beyond Good and Evil” and “:338” recorded live on the Y in Dub album?

Mark Stewart: Basically, what happened was, when we got the master tapes, we were trying to do some things. We had this idea of this Y salon with performance art and poet mates and whatever, and just doing these weird old pop-up things in these record shops, no sort of a big deal, just to launch Y. And I said, we’ve got the master tapes, why don’t we get our engineer to bring them and get Dennis to dub them on a mixing desk live from the tapes? So Dennis did that. And I was standing next to him and I was shouting at him and nagging him on. I was really dancing next to the bass bins in the Rough Trade shop with all these heavyweight fans, you know they’re virtually mates now, and it came out really, really good and it was a brilliant experience, it was like hearing my shit on a really good sound system, it was like a dream come true.

PAN M 360: Do you have the intention of making a dub version of the second album?

Mark Stewart: Now that you say it! I’m thinking about doing a Christmas single. Me and Gareth have been working on “Silent Night”, which goes really well with the lockdowns and the curfew over here. I was working with Lee Perry on some of my solo stuff just before he died. And I did a radio show with him and the guy from Wire and Cosey Fanni Tutti. I asked Cosey but I haven’t heard back from her yet, but I’ve just reached out to David Thomas from Pere Ubu. I like these versus things, like The Pop Group versus Pere Ubu’s Christmas song or something. We’re constantly doing stuff. I’m in a room surrounded by stacks of stuff. I’m working with all sorts of people on all sorts of different projects.

PAN M 360: What’s your definition of dub?

Mark Stewart: (long silence) I try and dub up my life. Dub is the music of chance, and to dub something is to flip it. Postmodernists call it deconstruction or something, but again it’s wide open. So dub is like being on the shores of endless worlds. It’s an index of possibilities, like a Rubik’s Cube, you know? And I love it. I was just listening to some Don Carlos stuff earlier on. My problem is when I go to soundsystems, I hear a tune out but I can never find the bloody tune because I don’t know all the names of everything, right? I used to chat to the old reggae singers, they used to just queue up and five different people would sing five different songs on the same rhythm section in the same day.

PAN M 360: And if push comes to shove, what’s your favourite dub album, then?

Mark Stewart: It’s not really albums, it’s tracks. There’s a track called “Stone” by Prince Alla, with all these lightning crashes and stuff, (singing) “I man saw a stone just come to mash down Rome”, or the dub version of “Jahovia” by the Twinkle Brothers… it’s endless, I could be talking about it for hours and hours! And every time I go on YouTube, people are posting these crazy dubbed versions of tunes I heard. There’s this classic club in Bristol called the Bamboo Club where I saw I Roy, The Revolutionaries, Style Scott… You know, it’s the love of my life. My friend from Primal Scream says wives come and go but your football team stays forever. It’s the same with dub. I think I’m still going to be playing dub tunes when I’m in a bloody old-punks retirement home.

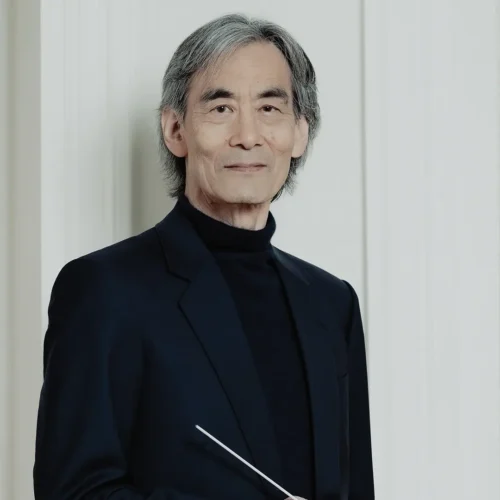

(photo : Chiara Meattelli)