Additional Information

Photo: Bo Huang

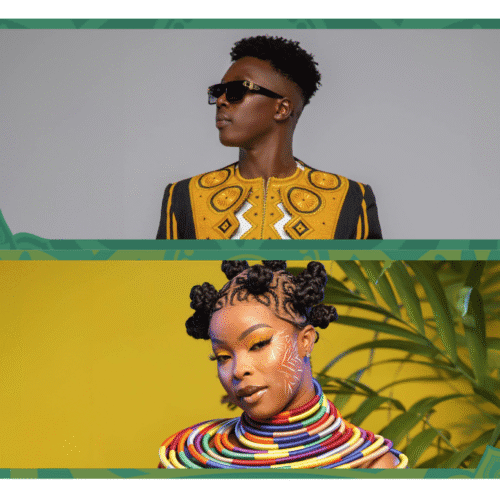

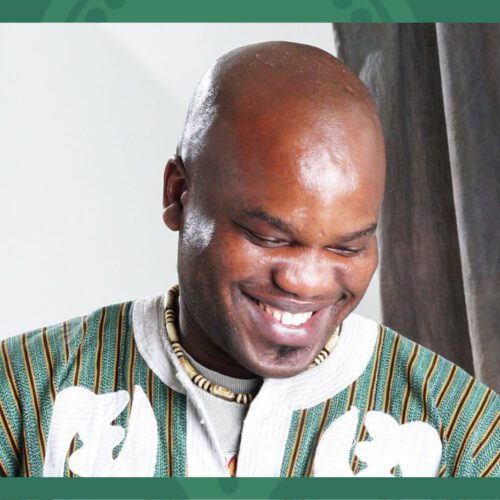

Pivotal Arc is shaping up to be the largest project led by Quinsin Nachoff, 46, a Canadian who’s been living in New York for the past dozen years. First on the program is a three-movement violin concerto featuring Quebec soloist Nathalie Bonin, whose career is divided between Montreal and Los Angeles. The concerto’s instrumentation includes bassist Mark Helias, drummer Satoshi Takeishi, and vibraphonist Michael Davidson, joined by a wind and string ensemble under the direction of trombonist JC Sanford.

The album also includes a four-movement string quartet performed by the Molinari Quartet, as well as the title piece of the album, another major work featuring Nachoff’s trio, and the wind and string ensemble consisting mainly of Montreal musicians: Jean-Pierre Zanella, Yvan Belleau, Brent Besner, David Grott, Bob Ellis, Jocelyn Couture, Bill Mahar. Performed by musicians from New York, Toronto, and Montreal, these works highlight Nachoff’s compositional imagination, at the confluence of contemporary jazz, contemporary music from the classical tradition, and hand-picked non-Western music.

PAN M 360: When was the idea for the Violin Concerto, the most imposing piece on the program?

QUINSIN NACHOFF: We recorded it right after the concert done in Montréal two years ago, so it was two years ago at the studio Piccolo in Montréal… amazing personnel, a bunch of excellent mics, that made the whole process so smooth and easy. There was an important amount of recording material we had to get through, many different takes, many options. We had to find the time to sit, make the decisions, and edit it with David Travers-Smith, the amazing sound engineer and technician involved in almost all my projects. It took a long time indeed!

NATHALIE BONIN: Because we were in different locations, New York, Toronto, Montreal, Los Angeles, that was difficult to gather everybody and achieve this project. It’s also very hard to get money for this kind of project, but thankfully we had incredible support from the Canada Council. That being said, it took a lot of time to do the application, and we had to wait a while because there were no funds at the early stage of the process.

PAN M 360: In what context was the concerto developed?

NB: In 2001, I went to the Banff international jazz workshop, where Quinsin was teaching. I was just exploring improvised music, that was really new to me. And then later, I played a piece composed by the trumpeter Dave Douglas, previously done for the violinist Mark Feldman. Douglas asked me if I would like to play, so there was a cadenza where I could improvise. For me that was a big first time. Then I performed this music over a week, and Quinsin heard me playing. He could observe I had strong classical training. Then came the idea of collaborating and touring; we started working on his projects like Magic Numbers, Horizons Ensemble, etc. Seven years ago, we were backstage in Toronto, waiting to perform a concert, and I asked him almost as joke, hey! What about a violon concerto? We both laughed, and…

QN: Nathalie is super busy, but we kept touch about this concerto project and slowly put it together. Supported by the Canada Council, a first demo was recorded in 2014 in New York, there was also a fundraising effort, and we were finally ready to record the music in 2018. Because Nathalie was previously involved in two of my big string-focused projects, I had a good sense of what she was capable of, which was really impressive. Then, I wanted to push her in a different direction because I knew she was comfortable in my previous settings. That was the time to put her in slightly uncomfortable settings and see how she could react. And again, Nathalie did excel. She worked super hard to figure out how to be herself in that. As a composer and improviser, I love being able to showcase musicians for what they are really great at doing, and then challenge them, putting them in some zone where they don’t know what it would sound like.

NB: And we’re still friends ! (laughs)

PAN M 360 : Quinsin, tell us about your choice to live in New York and pursue your career there for the past dozen years.

QN: I grew up in Canada, spent a lot of time in this scene there, I studied at Umber College in Toronto. So I really feel attached to Canada in a lot of ways. My family is still there, my sister lives in Vancouver. But I also enjoy being part of the vibrant, exciting scene in New York. It’s really challenging. For me, it was just the opportunity to get to work with people who are devoted to playing original and creative music. They’re just really driven and that resonates for me. And I don’t give up doing things in Canada, I get to work with amazing Canadian musicians all the time.

PAN M 360 : As for you, Nathalie, your career is divided between Los Angeles and Montreal. You can be found both in very pop contexts, either on the TV show The Voice where you are first violin in the string section, or in your “aerial violin” acts, or in the movie industry, where you’ve had success composing scores, not to mention these more complex and demanding music projects. Why such an eclecticism?

NB: I get bored easily. Being a steady member in a classical ensemble is like going into a monastery. So I need other challenges that inspire me. I like trying different things, for me it’s just life, it’s fun to live. So I embrace all that I can do, trying new things makes me discover new aspects about myself. I’ve never seen myself sitting down in an orchestra my whole life, I needed to play different music in different styles – jazz, world music, pop, entertainment, show business… I also started composing in 2010 and now, it is almost half of what I do, sometimes even more. So I can play great music, work hard on this concerto, or play on The Voice for millions of people – very different challenges, but still a challenge, and a different drive.

PAN M 360 : What is your appreciation of the Molinari Quartet in the context of this string quartet?

QN: That was Nathalie’s recommendation, it was phenomenal working with them for the first time. Great fit! Originally, I was going to do a workshop with them, with some of the material before recording it, but that couldn’t happen. So I brought them the music three or four weeks before the recording, and I didn’t get to hear a single note from them before the rehearsals. That was challenging, risky, and stressful. But when the musicians showed up at the rehearsal, they did an amazing job. They played the music even better than what I could imagine. They really got inside it! They were interpreting things differently and pushing the envelope, so they had an improvised feeling to it. You could tell they enjoyed the music as well. They were very open and really dug the rhythmic aspects too, having fun doing it. That was beautiful!

PAN M 360: To conclude, the title piece also merits consideration.

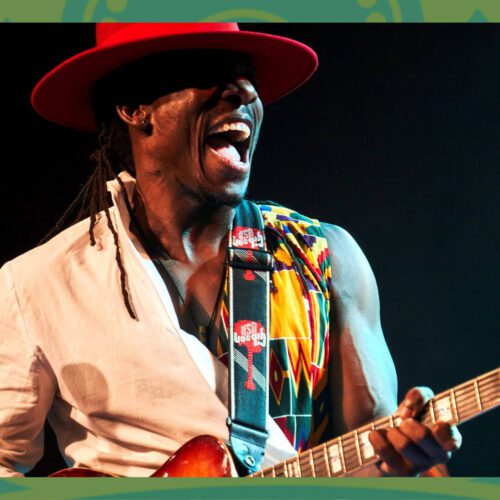

QN: “Pivotal Arc” was written in 2017-18. I was reading an excellent article in the New York Times about climate change, and I could see all these graphs illustrating global warming. Those graphics inspired a giant arc in me. Upright bass player Mark Helias has some solo commentaries at the beginning and the end of the piece, the saxophone plays at the peak of the arc. Mark is a tremendous player and soloist, he plays as well in jazz projects and classical music ensembles, large or small, he leads his own trio with Tom Rainey on drums, and Tony Malaby on saxophone. And we had such a great time with all those players. Every musician did their homework, when I heard all their preparation in Montreal, it was amazing.

PAN M 360 : Quinsin, your approach is rooted in both contemporary jazz and contemporary music of classical tradition, not to mention your love for tango nuevo and other global music. For your recent works, what have your inspirations been on the classical side?

QN: I definitely like the music of the first half of the 20th century – Bartok, Shostakovitch, Berg, etc. – but I also listened to more recent string quartets and chamber music, for example pieces composed by Brian Ferneyhough or Helmut Lachenmann. So I tried to expose myself to a lot of different music that’s happening now. I have pretty diverse interests in different styles and genres, and I try to find where things work well together. I avoid what doesn’t work between genres, and find areas where they have common elements.

PAN M 360 : Generally speaking, do you try to achieve a balance between written and improvised music?

QN: It just depends on the players I’m playing with. When I met the Molinari musicians, they made it clear that they would not improvise, so gave them some little aleatory things, something from their tradition. Playing with Nathalie is different – I know that she can improvise, she is particularly good at free improvisation. There are several moments in the violin concerto where I would give her start of a written cadenza, and the landing point of where the next section was. And then I just let her come up with her personality, and it’s going to be different every time. In other contexts, I can use the pianist Matt Mitchell, amazing improviser and reader, I can give him even more vague directions, just enough to kind of tilt the angle of improvisation… Or not at all. Sometimes I don’t give anything. Or very specific directions, very challenging with players coming from the jazz universe, where rhythms and chords are happening. So there are a lot of strategies, almost infinite ways. You just have to find what makes sense at the moment and serve your bigger purpose.

PAN M 360: For many of today’s music fans and musicians, the idea of “advanced” music increasingly implies the meeting of contemporary jazz and written contemporary music. Is it in this universe that the works of Pivotal Arc are situated?

QN: We must remember that most classical composers are improvising. They don’t do it in public, but that’s how they come up with ideas. Today, musicians and listeners who are more focused on contemporary classical music or universal performers, are also listening more broadly. “Serious” composers such as Nicole Lizée are not letting improvisation into some of their pieces, but they draw in a lot of popular styles of music, like rock, drum & bass, or pop. We are in between universes, musicians are now used to that. As I said, I try to find common elements of jazz and classical, African sources and occidental sources, where they work well together. I like to blend commonalities between them rather than forcing music worlds as a contrast. These are elements that we can weave in and out. Then we are never really sure – is it classical or is it jazz right now? It’s just not very important.