Additional Information

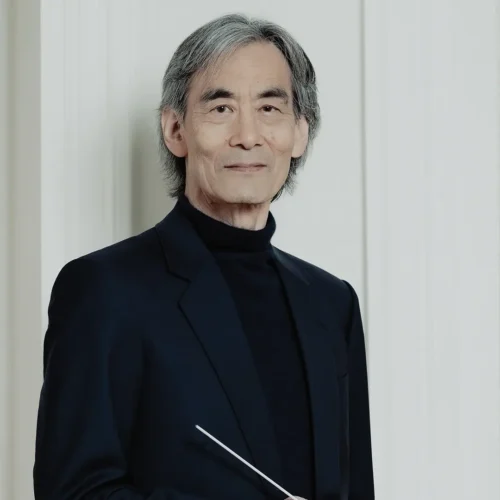

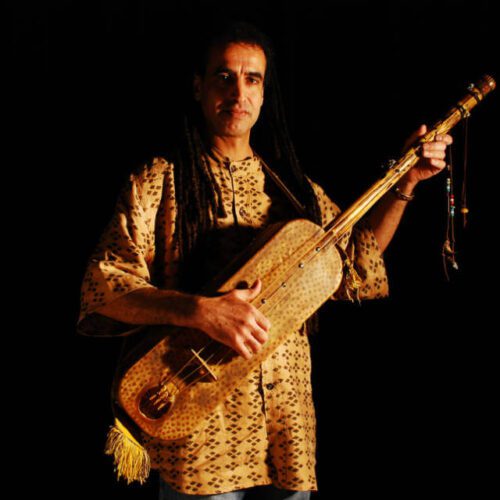

Photo: Yuji Moriwaki

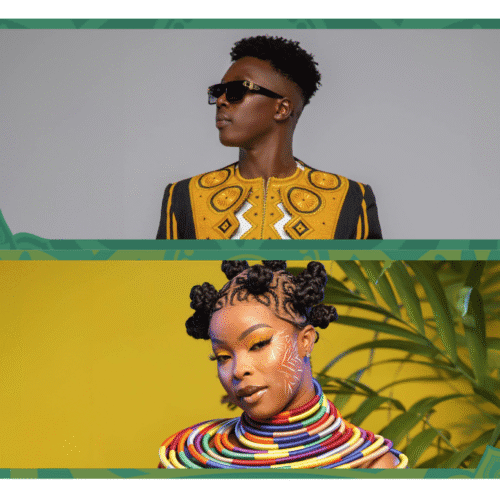

Minyo Crusaders and Frente Cumbiero are two groups “that come from very similar places,” says the latter’s band leader and bassist, Mario Galeano.

“Our focus is on music, not on commercial gimmicks. We are record collectors, and have an interest in digging into our roots, into traditional music. These are all things we share. Also, we have a common heritage, our ancestors crossed the Bering Strait tens of thousands of years ago and populated the whole continent. That is part of our native heritage. It’s like meeting our long-lost cousins.”

Guitarist Katsumi Tanaka, who founded Minyo Crusaders along with singer Fredy Tsukamoto in 2012, was seeking to hybridize, revitalize, and liberate minyo, the rich tradition of Japanese working-class folk music.

“One of the factors we thought was necessary to bring minyo back to life with a new approach,” Tanaka says, “was to not lose its fundamental vitality. Minyo was originally the music of ordinary people, but over its long history it has gained prestige, and been taken into the fields of art and traditional performing arts, and away from the people, because it has been treated too reverentially.”

The cumbia connection was already established for Minyo Crusaders with “Kushimoto Bushi”, from their 2017 album Echoes of Japan. Other songs on the record drew on boogaloo, reggae, Ethiopian jazz, and more, and the international re-release on the U.K. label Mais Um caught a lot ears worldwide.

“I think cumbia continues to maintain the vitality that minyo once had in the past,” says Tanaka. “They haven’t forgotten that it’s people’s music. That’s what minyo originally had. Different countries do not make a big difference when people try to have fun. It’s a simple and powerful feeling shared around the world. And when I replaced the shamisen phrase in ‘Kushimoto Bushi’ with a guitar, it had the same feel as cumbia. I immediately heard the guiro rhythm.”

The two band’s time together was a mere two days of activity, but it’s a time neither will soon forget.

“We are always learning, in each interaction with musicians,” says Galeano. “In this case, I have to say we reinforced the concept of how much of a difference it makes when the vibe is in the right place. When people are happy, and faced with the challenge of communicating, the most beautiful things will happen. If in collaboration with someone else, you want your concept to prevail, it’s going to be tough. There is very little space for egos, you need to flow with the group.”

“Through music, I was able to meet many people in Bogotá,” says Tanaka. “Mario and Frente Cumbiero, their community of friends, welcomed us with the best team spirit. Everyone was serious, emotional, and creative. I think that it’s an ideal example of taking full advantage of local characteristics, and working independently.”

Easier said than done, when over a dozen different musicians are involved.

“It was especially tricky from a technical point of view,” Galeano recalls, “but our engineer Dani Michel did a great job. We basically divided the chores between instrumental groups – the horns, the percussion, the harmonic base, the singers. We already had made arrangements prior to our encounter, so it was basically, get in the studio and start playing. After maybe an hour or so of developing the idea, we were confident, so we learned the parts and were ready to record the next day.”

The four-song EP’s first teaser track was a Colombian contribution, which of course earned an injection of Japanese flavour.

“It’s a classic originally recorded by Pero Laza y sus Pelayeros,” Galeano explains, “a cult band from the ’60s who put out some very nice cumbias that are classics today. The original name is ‘Cumbia del Monte’, so it just made total sense to extend the title to ‘Cumbia del Monte Fuji’.”

The most energetic, accelerated number on the EP is “Tora Joe”, in fact a festival song from centuries ago.

“The history of ‘Tora Joe’ is very deep,” says Tanaka, “and there are various theories about it, from the origin of the song to its content. It’s said to be the oldest festival dance song in Japan. Its original title is ‘Na-nya-do-yala’ – ‘nanyadoyala, nanyad nasalete, nanyadoyala’, repeated in the song, doesn’t make sense in modern Japanese. They’re like the words of a spell or incantation.

“Some believe that local dialects transformed it. The lyrics encourage people who are struggling to make ends meet by saying, ‘let’s do anything we can!’, and express the misery of the common people with, ‘I don’t know what is happening in the world.’ There are certain theories that the song is about a woman seducing a man by saying, ‘do as you please’. There is even a theory that it’s a song about Jehovah and David, in Hebrew. In the northern part of Japan, where this festive dance song became popular, in some areas they dance around a cross, which they call ‘the tomb of Christ’. It’s a very mysterious song.

“When you look at the lyrics, they use phrases like ‘Tono-sama (lord)’, ‘the most beautiful woman in town’, ‘celebratory food’, and ‘bright umbrella” – standard phrases often used in Japanese festival songs, which are stories about celebrities, famous incidents, ordinary people’s longings, and wealth, told by ordinary people. It’s said that people of various occupations, who didn’t normally interact, could participate in the nighttime festivals together. The lyrics would create a trigger, an opportunity for those people to be in the same place and release their everyday worries. Therefore, the lyrics have changed depending on the situation, and the wordplay has changed depending on the times. In minyo, there are many songs whose lyrics have been accumulated and passed down to the 100th version.”

“Opekepe”, meanwhile, is in fact a prototypical rap song. The Minyo Cumbiero version goes even further with it, deep into a dub style.

“The song isn’t exactly minyo,” says Tanaka. “It was written in the late 1800s for comedian Otojiro Kawakami to sing on stage. He used the stage name Jiyudoshi, meaning Freedom Kid, as a pseudonym for his anarchic, politically charged art. And at a time when repression was severe, he sang what he wanted to say in the lyrics of ‘Oppekepe’. He was put in jail dozens of times.

“The song has no melody, the rhythm and tempo of the narrative are important, and the lyrics are said to have been improvised and altered, a form similar to rap. Like ‘nanyadoyala’ in ‘Tora Joe’, ‘opekepe’ is also unintelligible, a strange word, like an incantation. Some say it means ‘throw it away’ or ‘let go’.”

The Minyo Cumbiero project is exemplary of a subtle but convincing increase, in recent years, of mutual cultural curiosity between Asia and Latin America.

“After the Second World War,” says Tanaka, “Japan tried to incorporate cultures from around the world as its economy developed. In the 1950s and ’60s, only certain people could access foreign culture. Even the educated musicians in Japan had no choice but to learn about foreign music by listening to U.S. military radio stations, and the vinyl records they obtained from soldiers. They had an excellent musical education and played Latin music with great dexterity, but with such limited access, every Latin band in Japan had to make ‘Besame Mucho’ part of their repertoire. Latin America was really far away.

“They presented foreign culture as a commodity to the Japanese populace, but I think they forgot to try to introduce Japanese culture outside the country. With the Japanese economy booming, domestic business was probably enough for them.

Tanaka happily observes, however, that times have changed.

“Now, not only certain wealthy people, but also the general public, can instantly exchange cultures and convey their feelings with people abroad on social media. Japan should delve into its own culture and present it to the world. I think that sharing the same feelings and emotions, rather than a one-way information intake, will create a new culture. Frente Cumbiero’s work so far is a great example of this.”

Galeano is enthusiastic about any uptick in interaction between the two continents.

“That would be amazing,” he says, “because we have, for the last centuries, been having to mediate our relations with Asia through Europe, so the more direct connections we can have, the better. There is quite a big underground, invisible, spiritual link between Asia and Latin America, as I say, because of our blood bond. Many melodies sung today by the indigenous Americans are originally from northeast Asia and Mongolia. There is even stronger proof that Chinese ships arrived on the coasts of Peru. The music of Peru and China are two sides of the same coin.”

It seems the same can be said of Colombia and Japan!

PAN M 360 thanks Megumi Furihata for her translation assistance.