Last night’s finale and premiere at the Maison symphonique de Montréal were one and the same: the Orchestre Philharmonique et Choeur des Mélomanes (OPCM) ended its season (the tenth of its existence) with a first-ever performance of a Mahler symphony, in this case the Second, “Resurrection”. Conductor Francis Choinière had chosen it for its beauty and magnificence, allowing him to showcase his orchestra’s capabilities. Soprano Sarah Dufresne and mezzo Allyson McHardy joined the ensemble for the short but beautiful lyrical lines of the work’s fourth and fifth movements.

WATCH THE INTERVIEW WITH FRANCIS CHOINIÈRE ABOUT MAHLER’S RESURRECTION SYMPHONY.

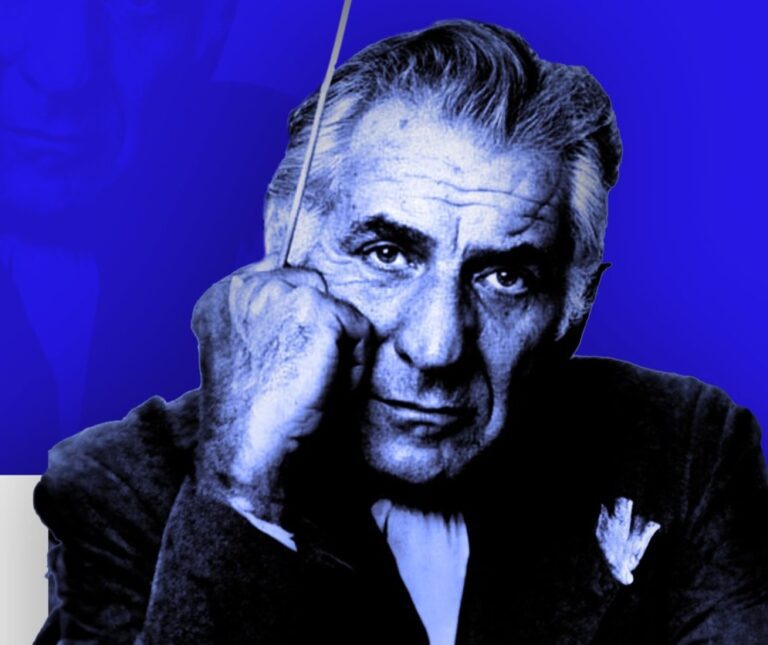

Francis Choinière conducts in a poised manner, without the effluvia of his Montreal colleagues Rafael Payare and Yannick Nézet-Séguin, or the historic Bernstein, a model in his own right. This induces an attention to the almost crystalline clarity of the score’s numerous lines and contrasts. Where Bernstein creates a gripping viscerality, Francis draws precise, more thoughtful portraits. This does not prevent the achievement of impressive and effective tutti when necessary.

I particularly appreciated the characterization he gave to the strings, very beautiful and rich in temperament. Hats off to the orchestra’s first chair, violinist Mary-Elizabeth Brown, who played some vibrant, very lilting solos.

The second movement, andante moderato, was beautifully pastoral and debonair. The same was true of the Scherzo (third movement), with its dance-like “allant”.

Urlicht, that moment of grace (fourth movement), gave us the opportunity to appreciate mezzo McHardy’s sound projection, a tad dark for the needs of the score, but given in a very pleasant tonal and aesthetic refinement.

The final movement, with its many dynamic pauses, is a formidable piece to tie down, for it must be ensured that the fluidity of the “ascent” to the final light, which begins here and ends in the next movement, is not diminished and rendered less penetrating by these frequent pauses. These must appear as mere breaths in a spiritually continuous ascent, despite the changes in texture and affect. I must report that, listening furtively to a few comments from the audience after the concert, this aspect of the work was perhaps not fully understood by all. If I myself did not feel the irremediability of this ascent during the unfolding of the movement, the choral finale ended up reconciling the purpose with the objective. Indeed, Francis Choinière led his 200-odd musicians to an apotheosis that (again, comments gleaned from the audience) sent shivers down the spines of many present, yours truly included. It was well worth the trip, for this grand tutti had panache! Heaven was reached, even if it almost had to wait.

As a good critic who has to quibble over technical details, I would like to note the lack of technical and aesthetic finish of the trumpets and horns in several delicate passages. If you want to play Mahler again, you absolutely must polish up this aspect.

All in all, a fine incursion into Mahler’s repertoire by a very young orchestra showing its aptitude for this demanding repertoire. There will be plenty of time to fine-tune the details and offer more in the near future to audiences who are often new to this repertoire, a specialty of this orchestra. This audience, considering its reaction, appreciated the experience and will be back in the future.

Thank you Francis and the OCPM for building tomorrow’s classical public in such a wonderful way.