Additional Information

At PAN M 360, we are joined by Quebecer Katia Makdissi-Warren, leader, founder, composer, and artistic director of the group Oktoecho, and Australian Corrina Bonchek, whose approach to combining contemporary creative music with traditional Indigenous music is similar to that of her colleague. Gathered in Montreal to complete an Oktoecho creation for the International Indigenous Presence Festival, Corinna and Katia explain their project, which aims to involve Indigenous artists in the theme of whales, a powerful animal symbol for many indigenous peoples and also an ideal example of the precariousness of marine ecosystems: Song to the Whales. This project promises to be an immersive show, including music, storytelling, and sounds from natural environments.

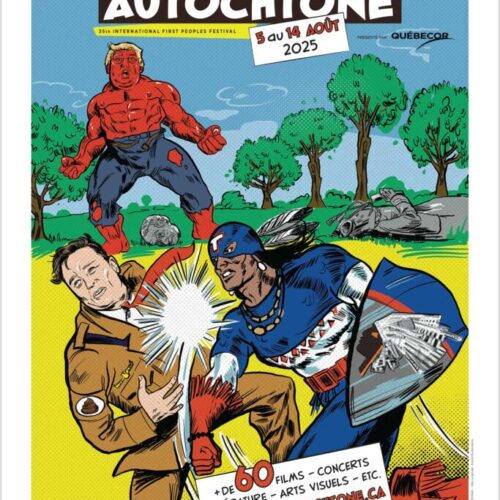

Presented on August 6 and 7 at 8:30 p.m. at Place des Festivals in Montreal, this production precedes a North American tour, following the 35th International Indigenous Presence Festival. Let’s see what it’s all about!

PAN M 360: This program looks very interesting because it is both an anthem and an environmental lament. Katia, can you elaborate on the foundations of this concept?

Katia Makdissi-Warren: Actually, we first met Greta Kelly, an artist from Corinna’s collective who attended an Oktoetcho concert at Cinars. “My God, it’s just like what we do at home,” she told us at the time. Then she put us in touch, hoping for a collaboration.

“It would be really great if we could collaborate.” We held videoconferences with Corinna and Maori singer Wahia Sonic Weaver, not to mention Inuit singers Nina Segalowitz and Lydia Etok, who are collaborators with Oktoecho.

The subject of whales came up because they are a powerful spirit in all indigenous communities around the world. The Inuit have been able to survive for millennia in the Arctic thanks in large part to whales.

So it’s understandable that the whale is a sacred animal, an extremely powerful symbol. And in this context, we all chose together to focus on the theme of whales, which is why we decided to invite Uncle Bunna Lawrie. It’s a pretty special connection!

Corinna Bonchek: I first met Whaia, who had already toured with the Aboriginal artist about ten years ago as a member of the Whaledreamers. Whales are extremely important to Bunna and his people, who live at the southern tip of Australia. From his grandfather, Bunna learned to sing to whales, even to call them.

So Whaia embarked on a wonderful journey with Bunna, sharing his culture and music and learning more about the relationship between the people and the whales.

This project has been very special since we all met, allowing us to establish a very strong artistic connection over the long term. Beyond indigenous peoples, whales question our relationship with the environment and lead us to reflect on our present and past practices.

PAN M 360: Do you all live nearby?

Corinna Boncheck: Actually, in different regions. It’s important to remember that Australia has more than 350 Indigenous communities that speak different languages. Music is largely responsible for our meeting and this connection, not geographical proximity. Our meetings take place in different locations in Australia and also elsewhere, such as Montreal, around the world, here in Montreal, and we share all the different music we have learned through our respective teachings, which includes Western classical music, music from Myanmar or China, and more. Although we have different backgrounds, we are very committed to raising indigenous voices and creating together this third space where we can bring different sounds and cultures and live better together.

PAN M 360: If we try to be more specific about the construction of this new work, what are the tools involved in this piece and how do you fuse the traditional voices and practices of these two regions of the world?

Katia Makdissi-Warren: Very different styles of traditional music are involved in the project. Bunna is a storyteller and a great advocate for whales on an international scale. He sings, but his style is perhaps a little more folk, yet he also introduces Aboriginal elements into his folk music. We are really different types of people and we want to be able to build something together. Since we don’t have much time, we have a week-long residency. We’ve been working for three days now, and things are progressing very well.

PAN M 360: Who composes what? How is the creative process shared?

Katia Makdissi-Warren: We started with pieces that Corinna had already composed for her ensemble, which are on the program, and a few pieces by Oktoecho as well. After that, we created new things together to make sure we had something that represented everyone. So we adapted Corinna’s pieces, we adapted mine. All this to try to create a coherent language, and also including two compositions by Bunna—because it’s his subject, it was important. So we started with existing pieces, adapted them, and created something new. That’s how we created the first stage of the encounter.

PAN M 360: Corinna, how did you initially construct your parts?

Corinne Boncheck: I think it works because the two ensembles allow for the coexistence of several musical languages developed by each of us. By coming together, our respective music selections have become extremely complementary. On my side, I work on very dynamic, intense elements, as well as gentler but fairly abstract things. Katia’s music, on the other hand, is rhythmic, multi-layered, and groovy. The combination of all these elements is absolutely wonderful! Add Bana’s songs to the mix, and we have this incredible musical journey to offer. Furthermore, there is plenty of space for the individual voices of the performers in the compositions. It is actually the continuity of their own creative voices that makes it work as a single entity.

PAN M 360: You are two Western composers working with indigenous artists. Are they involved exclusively for their traditional cultures? What is their creative role beyond their integration by you? Is there a danger of a colonial relationship?

Corinne Boncheck: For my part, I don’t write notes for soloists. Instead, I propose a kind of landscape, an offer of co-creation, which is also part of a general process of decolonization. And that’s how we get all the creative voices into the mix. I don’t compose for them as I would for a musician from the Middle East.

Katia Makdissi-Warren: It’s a co-creation, yes. And I think that’s really important. Everyone has to like what I offer enough to get something in return. If they don’t want to do what I’m proposing, they just say no, not like that. So there has to be enough creative space for everyone involved.

PAN M 360: Will there be a follow-up to this residency and creation?

Katia Makdissi-Warren: For me, it’s a long-term process. We hope to continue in Australia next year. For now, we are experiencing this first stage of wonderful encounters, first by modifying each of our pieces, then by composing new pieces so that each artist present can find their way and be welcomed into each piece. That Nina, Lydia, and the throat singers are welcomed into Corinna’s Gong pieces, and vice versa. That’s what matters.

We have really modified things so that everyone feels comfortable moving from one world to another, and this is already creating a certain unity.

PAN M 360: So this is a first step.

Katia Makdissi-Warren: As I said, we don’t have much time to prepare; there aren’t many new compositions, but we’ll keep working. The next step will certainly be even more cohesive. It’s really a step forward, I think, in any case, we’ll see with Corinna, but I think it’s a work in progress and that we can continue to develop something together to achieve even greater unity in the music.

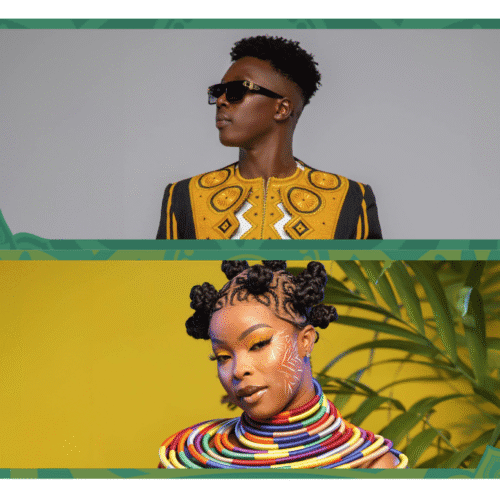

Co-directed and composed by Corrina Bonshek (Australia) and Katia Makdissi-Warren (Canada), in close collaboration with renowned artists:

Whaia Sonic Weaver – Maori singer

Uncle Bunna Lawrie – Aboriginal singer, storyteller, and activist

Nina Segalowitz & Lydia Etok – Inuit throat singers and co-artistic directors of Oktoecho

And musicians: Greta Kelly, Étienne Lafrance, Bertil Schulrabe, Michael Askill, and Jason Lee Scott