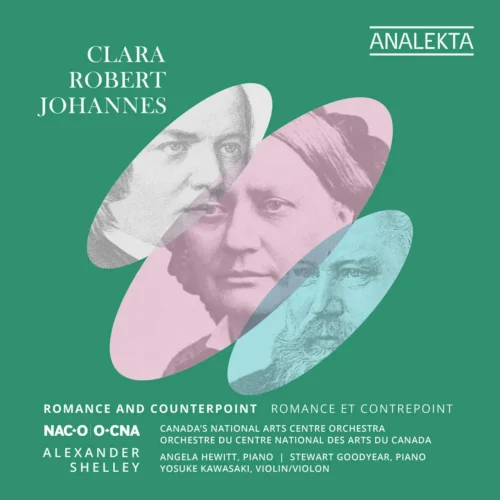

Triumph! Victory! The National Arts Centre Orchestra couldn’t be prouder to present Romance and Counterpoint, the final album in a years-long showcase of Johannes Brahms’s and the Schumanns’s incredible repertoire.

Symphony No. 4, composed by Robert Schumann, is a perfect encapsulation of the excitement of the album’s release. It’s a four-movement work that’s energetic and upbeat – a celebratory dance! – but it still has all the drama the listener has come to love about Robert Schumann. The violins are light, bouncing gleefully through the movements until the heavy brass section fights for dominance in the last section. In the end, they’re both ushered out by a proud drumbeat. It’s a work that evokes Robert’s mindset while he wrote in his later years – a lot of his output came from his manic episodes, where heightened emotions would likely have dictated the intensity of his music. To think these evocative, passionate works come from a time when Robert was struggling against mental illness plays well into the counterpoint theming of the album.

Three Romances takes a step back to observe Clara’s life: needing to juggle “the pressures of a solo career and motherhood” according to NACO, her music develops a subtlety, softness, and emphasis on the piano. It’s a sweet contrast to Robert’s works that outlines the vast range of their individual experiences, despite how entwined their music and personal struggles became.

Brahms’s fourth symphony acts as both the mid-point of the album and the middle ground between the two Schumanns’s styles. In the first movement, the prominent flutes combined with the light staccato violin notes give the work a playful gait, while the multitude of crescendos and the impactful drums and bass suddenly switch the tone to be more dramatic. Where Brahms always longed to be with Clara, he knew their marriage would never be possible, and as a result, the once valiant brass instruments become a lot more subdued in these movements.

Most of the album’s second half is dedicated to Clara. The piano becomes the anchor of the works, drawing attention to some of the loneliness she experienced because of her marriage. At the age of 19, her father refused to accompany her to France due to her continued relationship with Robert. The Romance in B minor was also written after Robert’s death as an offering to Brahms. These works bring down the energy for a nuanced and intimate view of the later parts of her life.

The final composition, by Stewart Goodyear, caps off this reflection. The improvisations on her themes are flowery and, although tense at times, always maintain a certain optimism. Despite the distinction at the time between male composers and “lady composers,” Clara broke through the mould, transforming ideas by musicians like Bach into innovative masterpieces. The incredible flourish at the end of this work says it all: the influence of this troupe of composers, especially when factoring in their interpersonal struggles, is not to be understated.