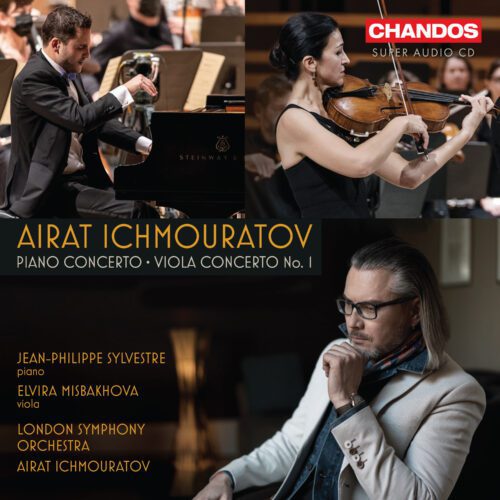

Airat Ichmouratov is a Quebec composer who sounds like the best of Hollywood. The Montrealer is fast becoming a leader in contemporary neo-romantic music worldwide. His compositions, traditionally structured as symphonies, concertos, quartets, symphonic poems, etc., are played just about everywhere on the planet. And with good reason: not only are they very accessible, they are also extremely well written and often remarkably orchestrated, like good film music.

Take the case of the 2012-2013 Piano Concerto. Right from the start, we’re on familiar and comforting ground: it’s Rach 3! Fast forward a little, and it sounds like Delerue. Later, there’s Gorecki too, in the orchestra’s relentless advance of sustained chords under the piano’s warning shots (2nd movement, grave solenne). The 3rd movement evokes Korngold in the initial explosion of colours, then a whirlwind of Saint-Saëns and Rimsky-Korsakov in the stunning, spectacular fresco that follows for almost ten minutes. The woodwind writing throughout the concerto is simply dazzling. One is reminded of James Horner’s great soundtracks of the 1980s and early 1990s (The Land Before Time, Willow, Star Trek II, Aliens, Krull, Cocoon, The Rocketeer, etc.) but, of course, with a purely and very coherent concerto approach. Jean-Philippe Sylvestre seems to vibrate with happiness with this luminous and heroic score, sincerely pompous, and ultimately damned irresistible.

The full album will be available on all platforms on Friday 16 June 2023.

The Concerto for Viola in G minor is less exuberant, but just as rich in cushioned harmonies and orchestral moiré. Sprinkled with occasional folk elements and, above all, bathed in an engaging elegiac lyricism, the Concerto benefits from the benevolent attention and fluid playing of Elvira Misbakhova, also Ichmouratov’s partner.

It is quite fascinating to be so easily drawn into music that you know to be totally imbued with a musical aesthetic that dates back more than a century. This is probably because, while Ichmouratov is clearly (and deliberately) heir to the great Romantic tradition (Rachmaninov, get out of that body!), he doesn’t just copy it like a cake recipe: he propels it into the 21st century with an orchestral opulence and a precise type of harmonic richness reminiscent of Romanticism… in film. But the latter has finally been accepted by the modern scholarly music establishment. As a result, contemporary composers who want to make melodic music can plunge headlong into it without feeling the need to add chromatic spices that end up creating an in-between style (neither too modern nor too ‘accessible’, a word long shunned) that has never really found its place. The Montreal composer’s music is romantic, of course, but a romanticism that has been through decades of Hollywood. It couldn’t have been written as it was in 1920, or 1890, for example.

Ichmouratov’s music is therefore a grandiose pied-de-nez to the psycho-rigid purists who have for so long imposed a shameful atmosphere on pleasure in contemporary music. And yet, if this music is eminently enjoyable, even exciting, will there be anything left of it a century from now? Will it have replaced astringent modernism for good, the latter reduced to an ephemeral cerebral fad? Or, on the contrary, is it itself a fad, a need for temporary consonance after decades of hyper-demanding avant-garde?

They say whoever laughs last, laughs hardest. But whom exactly? With all due respect to both esthetics, the jury is not out yet…