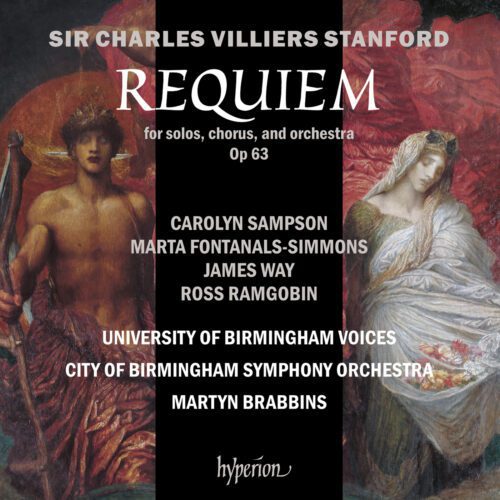

This Requiem op. 63 by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) is a rarity on record. There was a pioneering recording on the Marco Polo label (later reissued by Naxos) more than 25 years ago, with Irish forces. A good version, but now largely surpassed by this one, from the very British Birmingham, where, incidentally, the Requiem was first performed in 1897.

Martyn Brabbins and his very fine local forces (the University of Birmingham Voices and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra) have a close affinity with this kind of music, solidly romantic, Brahmsian with a French tendency in certain colour schemes. The orchestra sparkles under Brabbins’ baton and the choir shines. The soloists (Carolyn Sampson, soprano; Marta Fontanals-Simmons, mezzo-soprano; James Way, tenor; Ross Ramgobin, baritone) have character and a fine grasp of the desired discourse, made up of an assertive lyricism but imbued with an undeniable spiritual restraint.

This is important, because the essence of this Catholic mass set to music by the Protestant Stanford is all there: in this amalgam of grandeur and sobriety. The grandeur certainly comes from the Catholic ritual itself (which tends towards excess) and from other requiems composed previously (Mozart, Verdi, Brahms), as well as from Stanford’s lyrical fibre (he wrote no less than 9 operas). The sobriety comes from Stanford’s Protestantism, but also from his experience in writing Anglican hymns. The result is a work written for imposing forces, both vocal and instrumental, but which are used sparingly, with very few ostentatious outbursts, no terrifying explosion of sound like Verdi’s, and plenty of light, a soft, beneficent light.

Stanford’s writing concentrates on clear themes and melodic lines. He very rarely resorts to massive tutti, and when they do arrive, it is at the end of sustained crescendos that gradually prepare the listener. The Tuba mirum, the Quam olim abrahae promisisti (an energetic fugue) and the Sanctus are the best examples, with the latter radiating seraphim and warmth. Here, a finely balanced opulence rather than a muscular outburst.

Elsewhere, and for the vast majority of the work’s 75 minutes or so, we are treated to tender, measured passages, where the strings gently quiver beneath angelic choirs, leading us into contemplative, celestial considerations. This Requiem never wallows in threatening darkness. It chooses hope and redemption. It emphasises Renewal rather than Damnation.

Without having the same instrumental poetry, the Stanford Requiem undeniably has certain similarities with Fauré’s Requiem. It should also appeal to lovers of the latter. Propelled by the quality of the performance and the generous, full sound recording, with no loss of detail, this is a wonderful discovery for those who weren’t familiar with it and an absolutely definitive version of this masterpiece.