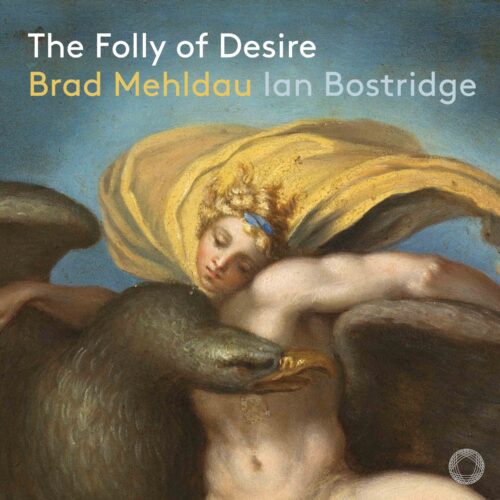

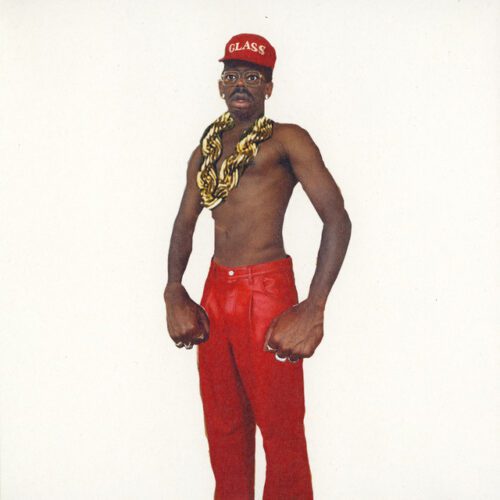

This is a surprising album. Surprising because, on the one hand, jazzophiles will be surprised to see a classical tenor alongside the great jazz pianist Mehldau, and on the other, classical music lovers will be perplexed by the prospect of listening to a new cycle of contemporary lieder by a jazzman. Even if, in the latter case, the surprise is not entirely justified, as Mehldau has already dared this kind of exercise twice before, with Renée Fleming and Anne Sofie von Otter.

The Folly of Desire touches on a universal subject, sexual desire, but from a… delicate angle. That of lust, sometimes violent. In this age of #metoo, the message conveyed by Mehldau in the programme notes about the retreat of a certain sexual freedom and an invasion of privacy can easily be, shall we say, misperceived. Unless it’s deliberate! I confess I don’t know, and I don’t want to put words in the artist’s mouth. Especially as Mehldau associates the notion of consent with it, which still saves the day. The ambiguity also comes from the fact that these are not his words, but rather those of great authors and poets, all male: Shakespeare, Blake, Yeats, e.e. cummings, Auden, Brecht, Goethe. A perspective that is certainly rooted in the undeniable genius of these authors, but which, combined with the modern context, could easily turn this plea into a missed opportunity to promote a wider range of viewpoints. Let’s not go any further: this is about music, not politics.

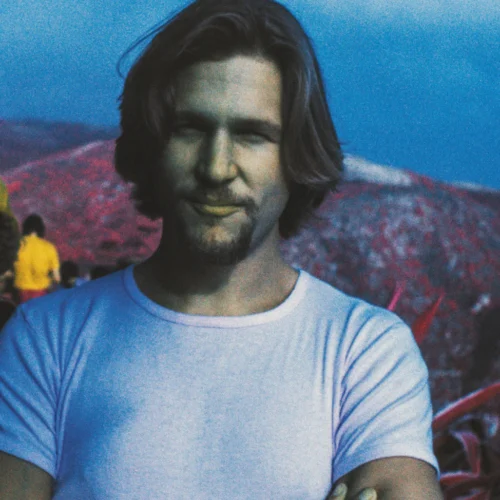

The Folly of Desire is a complete cycle, displaying a wide range of emotions and affects, from suffering to anger, from lust (poetically manifested) to regret. The score, either for piano or for Bostridge’s voice, is set in a modernist post-romanticism, bathed in harmonies that are spread out, stretched and complexified by jazz-inspired additions (of course). Bostridge is more than adept at seizing the slightest opportunity to clearly assert an emotion, or to sublimate its intensity. He has his work cut out for him here, especially as Mehldau, a brilliant jazzman but unaccustomed to accompanying a lyric singer, doesn’t always give him the space and time he needs to support and lay down the words. In the end, either he pushes or Bostridge doesn’t follow. In addition, the two friends offer us some very jazz standards (These Foolish Things, Night and Day, and others) as well as a very romantic lied by Schubert (Nacht und Träume). A way for each musician to step out of their usual comfort zone.

Aside from these sweet pieces, which have been adequately rendered, we now find ourselves with a cycle of modern Lieder that certainly raises a lot of questions about its intentions, but which above all offers an incursion into a musical panorama that is dense but highly attractive to future performers who will want to explore all its possibilities and symbolic interstices. After a first listen (and even a second, third, etc.), the real question is not: do I like it or not? Rather, it’s: when will I be able to understand its true meaning?