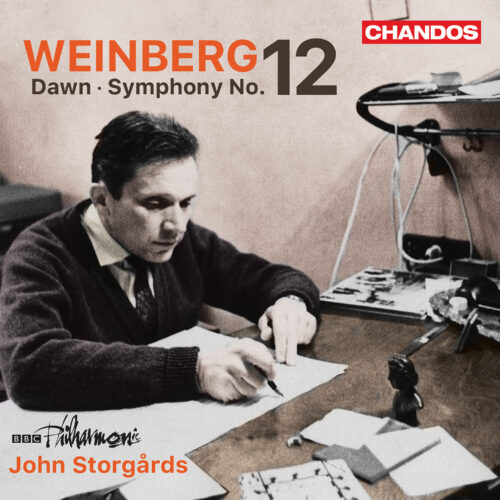

Mieczysław Weinberg’s musical debt to Dmitri Shostakovich is immense. For music lovers who love the latter, the music of the former is an absolute must. The same kind of sonic universe, the same plunge, more often than not, into dramatic outpourings of hyper-romantic character, but clothed in modern harmonies and melodies propelled by purposeful rhythms and often screaming with action and intensity. But Weinberg wasn’t just a placid imitator. In truth, he was a close cousin (artistically) to Shostakovich, but with his own personality. That’s what makes his music so delightful for anyone who marvels at the power of his abundant and often plethoric writing (particularly in the case of his symphonic works). This album bears powerful witness to Weinberg’s attachment to this aesthetic, while also demonstrating the composer’s ability to transcend his spiritual master.

The symphonic poem Dawn Op. 60 is pure Shostakovich in its melodic outbursts and dark orchestral magnificence. There are superb, infinite shades of grayness in the woodwind lines, like tragic, if seductive, laments. Here and there, the orchestra takes on a cinematic quality. It could be Eisenstein. The tonality goes from C minor to C major at the end of the 18 minutes (a Beethovenian path). But the light typical of C major remains discreet here as if filtered through a cloudy veil. It’s like an uncertain dawn breaking. Yes, this is 1957, the Soviet Union, after all. The time for illusions was long past, except in official propaganda. But artists like Weinberg and Shostakovich were no fools.

Symphony No. 12 Op. 114 “In memoriam Dmitri Shostakovich”, as its title suggests, is Weinberg’s tribute to Shostakovich. But it is also, ironically, one of the symphonies – at least up to this point in Weinberg’s career – in which he departs furthest from the style of his mentor and friend. The work opens with grating harmonies, which rub against each other with a rough edge. A few woodwind passages recall the dreamier episodes of Shostakovich’s 10th, then the orchestra becomes tense, nervous, and anguished. The 1st movement spends its time stringing together such contrasted episodes, with woodwinds and strings in turn delicate, mysterious or emotional, and intense tutti. This long movement (20 minutes!) ends without a flourish, in a kind of discursive, uncertain and almost slapdash no-man’s-land.

The Scherzo is relatively poised in metronomic terms, but gives an impression of implacability, due to its march-like cadence rather than true classical scherzo. Mocking tirades in the woodwinds give it a sardonic, even cruel character. It sounds like a macabre procession of freaks with picks and shovels on their way to topple some provincial magistrate… I love it.

An Adagio follows, desperately sad, as arid as the hardened bed of a dried-up river. The strings paint this portrait, without modesty, heavy with indifference. And yet, life clings to them, in a battle of every moment illustrated by, once again, the woods, demonstrating their irrepressibility as best they can, despite the assaults of a force whose only aim is to crush them.

The finale is launched by the marimba, playful, almost joyful! But the marimba is soon overtaken by the darkness of the strings. He persists, even inviting the strings to join him. The playing develops like a grotesque, sardonic round, reminiscent of the Scherzo, but this time, the ghost of Shostakovich is not only invited but actually present at the festivities. The festivities light up, or at least try to. No easy task, however, as the dreariness and sadness of the music continue to impose themselves, bringing the listener back to feelings of disenchantment. The battle is finally won by these, as the symphony ends in a slow funeral coda, a lucid tribute to the great Shostakovich: his life was never sunny. Why pretend?

Weinberg has rarely been so far removed from his mentor in this symphony. Radical modernity is insistently in evidence here, and the composer’s elective affinities with his predecessor are regularly overwhelmed by a need to broaden the palette of his expressive possibilities. A great work, rendered with great emotional power and a wide range of chromatic shades from gray, cloudy veil to opaque anthracite.

A masterly album.