Additional Information

TJIW Photos: Ed Marshall Photography

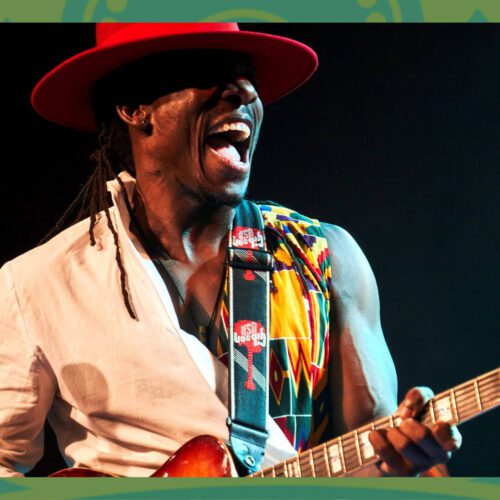

Jeanty, Momin recalls, “was the first person that I met who was channeling electronics with this spiritual vibe. I’d never really experienced that. I’d only heard experimental electronics like blips and screech, or very much four-on-the floor techno in New York. So it was incredible to hear experimentation rooted in Haitian rhythms, and have it still be all digital.”

“Working with Momin has been exciting,” says Jeanty, “because in the Indian culture, the music is very spiritual. So, we have that connection instantly. And he’s also very progressive, pushing it as far as using triggers, using Ableton Live. That’s the stuff that I love. It’s just great to have similar aspirations as far as keeping connected to the culture, but working with electronic instruments.”

PAN M 360 corresponded with TJIW for more insights into what they do.

PAN M 360: When we posted about the video for your track “Our Reflection Adorned by Newly Formed Stars”, we took the opportunity to establish a new category in our database – drum music. The term doesn’t necessarily mean music that’s exclusively drumming, but rather, that’s centered around drums and percussion. Do you think the term is accurate in the case of TJIW?

Turning Jewels Into Water: Of course, lots of music ensembles out there, from Afrobeat to salsa, come with a large percussion section – which is necessary to propel the music. While the percussion becomes an essential component, it’s not the only thing that defines the music, as there are plenty of other melodic and harmonic elements in play. In a similar manner, I’m more inclined to think of our own music as “folk music from nowhere”, as we’re also taking melodic inspirations from global folk music traditions and blending them with Haitian, Indian, and other rhythms from underground dance music, such as kuduro and gqom.

PAN M 360: Because drums, beats, and percussion – the sounds of which a brief and pronounced, rather than sustained or extensively variable – are so fundamental in your music, it feels like there’s a strong sense of space, of the positioning of sounds within space.

TJIW: Indeed! To follow up to my point above, while we certainly derive musical inspiration from those melodic elements, we do write the tracks with the rhythms first, so what you’re saying makes sense. We’re also blending digital and analog elements along with samples and field recordings, which helps add a sonic richness and spaciousness to our sound.

PAN M 360: It’s mentioned that there is an aspect of ritual to your music, which I can certainly hear. Rituals have a purpose, an intended outcome. What are yours?

TJIW: Our musical rituals focus on using drones, repetitive patterns and ancient chants to take the listener on a musical journey through their subconscious realms. We hope to instill a reflection on the present state of things, and also hope to inspire change and positive action.

PAN M 360: One cool thing about percussion-based music is it allows a lot of room for other musicians to get on board, so to speak – and dancers too, opening up even wider creative possibilities. What can you us tell about the collaborations on your record?

TJIW: We strive not to simply be performative of our individual cultural identities. I’d approached various guests and remix artists who were challenging norms in their own way.

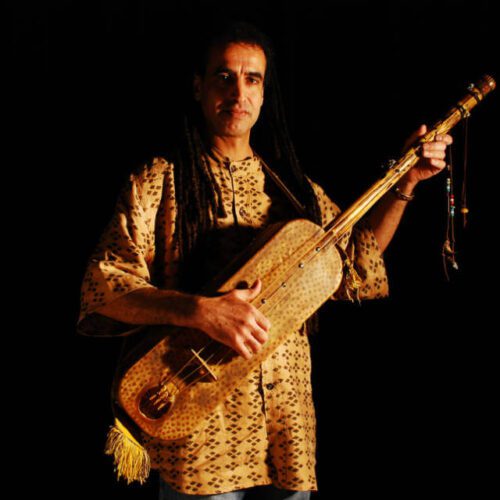

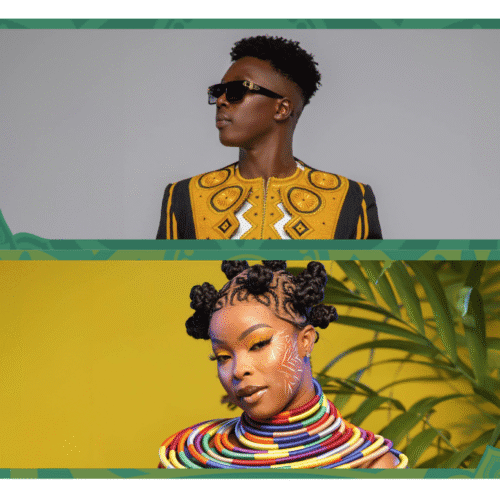

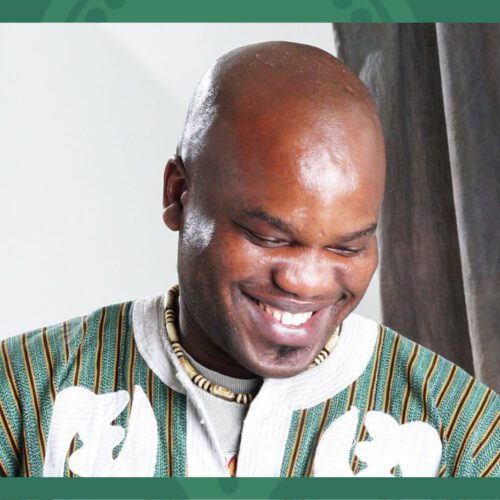

Iranian singer and daf player Kamyar Arsani, based in Washington D.C., is just as comfortable with punk rock as he is with traditional Iranian music. Mpho Molikeng, a master musician of South African indigenous instruments, based in Lesotho, also works with electronic musicians. Producer Laughing Ears is based in Shanghai, and is as influenced by Buddhist chants as she is by footwork. EMB is a producer and drummer from Réunion Island who combines her African heritage with techno and other electronic music as well.

We’ve also always worked with different types of dancers in live performances as well as video shoots, to further highlight the ritual aspects of the music.

PAN M 360: I’d like to zoom in on the first track, “Swirl in the Waters”, to find out more about it, and about Kamyar Arsani’s involvement.

TJIW: Kamyar runs a broad range of music, as mentioned. For this track, I’d specifically asked him to create lyrics based on the importance of water for human beings, without giving him further guidelines. He ended up with a beautiful poem in Farsi, which focused on the contrast between the vastness of an ocean and the shrinking timeframe for addressing climate change. The driving percussion, which is the focus of this song, is a blend of Iranian rhythms and vogue beats.

PAN M 360: “Kerala in my Heart” is a particularly fun track. In an odd way, it makes me think of the big beat genre of the late ’90s, Fatboy Slim, Propellerheads, and so on. What can you tell us about that track?

TJIW: Rhythms from Kerala collide with chopped and spiced vocals, while melodic fragments of the kombu, an ancient wind instrument only found only in South India, harmonize with vintage synths to capture the spirit of the street festivals of Kerala that exists in my heart.

PAN M 360: Art Jones’ video for “Our Reflection”, mentioned above, speaks to the story of the Siddhi, an Afro-diasporic community in India and Pakistan. I think their story merits some mention.

TJIW: the Siddis are believed to have descended from the Bantu people of the East African region who first came to India in 628 A.D. They were merchants, sailors, mercenaries, and some even rose to political power within Indian territories. Their population is currently estimated to be around 350,000, mainly in the states of Karnataka, Gujurat, and Andhra Pradesh in India, and Makran and Karachi in Pakistan. Siddis are primarily Muslim, although some do belong to other religions as well. They have been marginalized and are not considered a part of mainstream societies.

As the Black Lives Matter movement rightfully gains prominence in the world, it’s important to note that anti-blackness is embedded in most Asian and Arab cultures as well. Siddis have had their histories erased, and as a child growing up in Mumbai, I never learned about Janjira, Malik Ambar, the African Hashbi Sultans of Bengal, Sidi Saeed, or other luminaries.

We all have a responsibility to address the anti-blackness that is systemic and deeply rooted across the globe as well, before meaningful structural change – and regime change – will be possible.

PAN M 360: Looping back to the topic of terminology, another descriptor I’m inclined to use is “supernational” – transcending formally recognized borders. There is, appropriately, a marvelous international movement, predicated heavily on drums and electronics, addressing this idea musically. Strongly rooted, but also fiercely forward-moving. TJIW strikes me as very much part of that.

TJIW: I don’t think I could have said it better than this. For sure, I’ve always sought to create “music without borders,” even with past projects I’ve led such as Tarana. In TJIW, I’ve still preserved those aspirations, and I hope to create a music that can be cerebral and body-shaking simultaneously.

PAN M 360: A common feature of this musical movement is an inclination to create music for a sort of imaginary “somewhere else”. I wonder how much this reflects a restlessness, a dissatisfaction with where one is at any time. What do you think?

TJIW: It’s not so much restlessness as it is a reflection of our hybrid influences. Especially given that we live in Brooklyn, New York, which is truly a meeting of all races and backgrounds. That dissatisfaction to which you refer can stem from the frustration with a world presently focused on artificial borders, and denying the human history of constant migration.