Additional Information

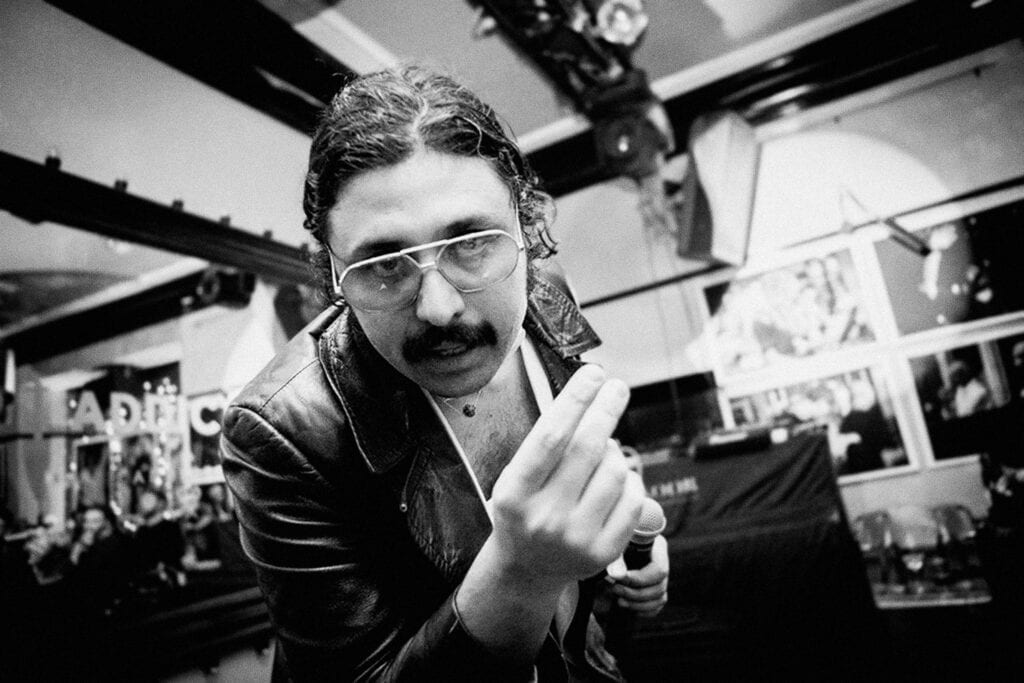

Tragic, funny, disturbing, strange and sometimes even moving, the ineffable performer Bernardino Femminielli leaves no one indifferent. Although he left to try his luck in Paris in 2019, it was in Vancouver that we located the colourful character, in quarantine with his wife, muse and collaborator Thea and their dog Poulet. Back in Canada for an indefinite period, the Montreal artist spoke at length about the reasons for his move to Paris, his worries and questions, and his mini-album L’Exil, four experimental French songs that serve as a kind of prelude to two other albums to be released in the coming months.

PAN M 360: You recently returned to Canada – what was your experience of the COVID crisis in Paris?

Bernardino Femminielli: We were in Paris during the whole lockdown, without ever leaving the city. I found it really intense, but we lived it well because we stayed productive. We were able to finish a lot of the stuff for the album, edit videos… It gave us a break from the Parisian drive, and a lot of other things too. It gave us a break from the Parisian drive, and a break from the rest of the world as well! We’re in Vancouver for a while, but I don’t know for how long. The idea is to go back to Paris, but our plans are still a bit vague. We’re keeping one foot here and one foot there.

PAN M 360: Tell us a little bit about L’Exil. Although it’s a prologue to two other albums that will follow, it’s not quite one itself. And is it a mini-album or an EP? Because, although there are only four songs, it’s still 40 minutes long!

BF: Let’s say it’s a mini-LP rather than an EP. It’s a pre-conclusion to a trilogy and not a prologue, because the two other albums, which haven’t been released yet, were recorded before L’Exil. I was looking for what to do with these two albums, and it wasn’t easy with this transition between Montreal and Paris. I wanted to find the right angle, the right way to present these two albums. So L’Exil became both a gateway and a conclusion to the whole process. It’s all based on new sessions of Plaisirs américains, on which I’ve taken a different tone and lengthened. I gave myself more time to tell a story, in a more personal way. I think the four tracks on L’Exil corresponded well to what I was looking for, in terms of emotion. Something dense and visceral, but also something with good sound quality, songs that the listener would have no trouble getting into.

Despite the experimental or abstract side of these songs, there’s something seductive and bewitching about them. It’s a lot less glamorous than Plaisirs américains. The album has a very political and personal tone. It’s practically the diary of someone who’s relearning to live on a daily basis, and who wants to deprogram himself for having suffered the misfortune of a corrupt system. The album takes stock of my past life and the despair I was experiencing in order to achieve artistic success. I talk about success but I’m aware that success is not something palpable and immediate. I learned to look at success as a struggle to become a better person, one who understands his abilities, strengths, and weaknesses. I fought to get my lucidity back, and I hope I will keep it.

PAN M 360: This exile from Montreal to Paris is the basis of this album – it was not an easy start. You had problems with the American legal system, your adventure in the restaurant business (Bethlehem XXX/Femme Fontaine) ended badly, and maybe you felt misunderstood as an artist here?

BF: This album is like a synthesis of many traumas. It’s the story of an entertainer who’s starting to lose his mind because his restaurant is sinking, he’s being screwed by everyone. He’s naive, he lacks experience, but he’s cunning. Except he’s too generous and people take advantage of him. His livelihood is doing his one-man shows, performing, touring, which allows him to exorcise his demons. I named this character Johnny. He’s a bit of a clown, a tragi-comic character. So, this Johnny, it’s a way of dividing myself in two and being able to express my life from another angle. It can also be a fragmented projection of myself and my problems. So, his life goes adrift and at one point he decides to run away with his wife. This exile is also a mental exile.

But the important thing behind all that is to learn to make peace with yourself, with your demons, with your frustrations with the music world and the capitalist world. Bethlehem XXX was originally an anti-restaurant. It was a place of experimentation where one could freely invest oneself in the form and thought of performance. Then big financial problems killed the Beth, but not the spirit, whereas for La Femme Fontaine, it was gradually the spirit that was poisoned by business and pretension. Despite the efforts you want to put into it, to have a restaurant or a business in Montreal is to live amid organized corruption, theft, mediocrity, sabotage, and indifference. A lot of big talkers, small doers… I believed in community, but individualism always takes over. It was time for me to take a break from all that. As I’ve always loved Paris, as I’ve always been welcomed there, and people there seem more receptive to my work, that’s where I chose to settle down. It’s also more convenient for me to travel around Europe and present my shows, make contacts, create opportunities. What I want is to be able to live from my art as I see fit, without having to make compromises, and in Montreal, that was impossible. Anyway, I don’t know what I would do if I didn’t do that!

PAN M 360: What is the borderline between derision and sincerity in your work?

BF: “The ideal is to have a poetic relationship to life, to everyday life, and not to need a stage to practice it.” I find this quote from actor Denis Lavant very inspiring. I play with grotesque stereotypes – the pathetic, oppressive macho man and the debased, giggling, intoxicated gigolo dancer. The audience is invited to laugh at these characters and ultimately condemn what they represent. I try to explore the character from the outside to the inside. I like to bring the style of the double act in my performance: the grotesque contrasts with the sympathetic character, where both make political and social statements to the audience and one shows the other, even though I’m alone on stage. I try with all my strength to always be as convincing as possible. I think that what people feel is something honest and frank.