“Breaking down barriers between genres and provoking encounters”. That’s how Isabelle Bozzini introduced the first evening of three concerts in Montreal for the fourth edition of Québec Musiques Parallèles (QMP), a decentralized contemporary music festival with programming spread across several cities in Quebec and New Brunswick. The first evening featured a double bill, with the performance work Ce qui reste quand la peau se détache du corps by Sara Létourneau and Chantale Boulianne, and Sara Davachi’s Long Gradus performed by the Quatuor Bozzini (Isabelle Bozzini, cello; Stéphanie Bozzini, viola; Clemens Merkel and Alissa Cheung, violins). The meeting of genres was indeed on the agenda, with two works in very different formats.

The latest in a collaboration initiated between Davachi and the quartet in 2020 as part of Composer’s Kitchen, the quartet’s professional creation residency for up-and-coming composers. Davachi’s work plays on the notion of time and its elasticity. Made up of four parts, the piece develops through a slow, sustained succession of notes that create a suspended effect, haloed by the carential chords that are played. There is no great acrobatic virtuosity in this work, but stamina and strong technical mastery to control the equality of the sound flow and make the different pitches evolve. The intensely meditative atmosphere contrasted dramatically – perhaps a little too dramatically – with the performance of Létourneau and Boulianne in the first half.

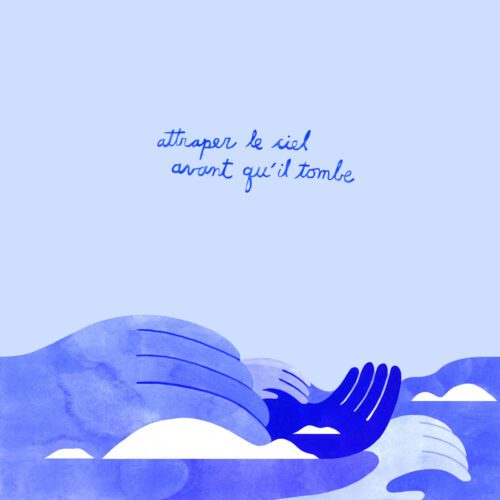

As soon as we enter the Théâtre La Chapelle, we enter the creators’ universe, with a dense scenography on stage: two wooden arches, suspended light bulbs, various structures in different shapes and a sound console welcome us. A show at the crossroads between performance art, sound art and scenic devices, the work is a journey in which different tableaux unfold before our eyes and ears. The show plays on themes of physicality, anguish, life and death, featuring a sound environment and, above all, the unique, oversized instruments crafted by the artist duo. Over the course of the 75-minute performance, the artists unveil musical tableaux featuring instruments of their own making, competing in ingenuity and symbolism.

A giant bellows – made following a training workshop with an accordion maker – that creates wind and makes metal mobiles vibrate, a counterweight bass whose pitch is determined by the mass applied to it, the rond-koto, are just some of the elements that mark out the structure of the work, all amplified and magnified by the lighting effects and sound treatments that invade the space. We’re swept away by the performance, impatient to discover which new instrument will emerge from the space, what sound it will produce and how. One of the highlights of the performance comes when the two artists perform a violin-making act before our very eyes, creating a huge instrument backed by a mechanically rhythmic soundtrack.

As the performance unfolded, musicologist Christopher Small’s (1927-2011) term musicking came to mind. In short, for Small, music is not a noun, but a verb. The term implies that performance is central to the musical experience, and the act of performing includes both performers and audience. Every element, from the making of the instruments to the intermediality of the artistic process, the sound of footsteps, the theatricality of gestures and words, the marbles that fall and roll randomly, the switching on of a light, the movement, the audience’s reactions: all these constituent elements are part of the work and are music. That’s what makes it unique and accessible.

So, what’s left when the skin comes off the body? A complete, captivating work, but above all a performance-experience that can’t just be described in words, but must be heard, experienced and seen.

Photo Credit: Le Vivier