Manu Dibango was asserting himself as a decisive conductor of global pop culture. A fiery arranger, an inspired composer, an efficient saxophonist (tenor and soprano) who also flirted with French pop (tenor with Nino Ferrer, organ with Dick Rivers), he was first and foremost a great conceptual leader. Among the best African musicians from the 1950s until his death, Emmanuel N’Djoké Dibango proved that modern Africa had much more to offer than a repertoire of traditional music, however rich and diverse it might be. (Alain Brunet)

To pay homage to him, PAN M 360 suggests five essential albums from his immense discography.

1972: Soul Makossa

1972: O Boso (Soul Makossa)

Active since the ’50s and, although he was part of the variable geometry of Fela Kuti’s collective Africa 70, it was with this album, released in 1972, that the Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango really made himself known throughout the world, particularly thanks to the success of the now-classic “Soul Makossa” and its magical mantra, “ma-mako, ma-ma-sa, mako-mako-ssa”. This song – originally commissioned by Cameroon’s Minister of Sports, who wanted an anthem to support the national soccer team – found its way into the hands of a few New York disc jockeys, who quickly adopted for at their parties. It has since been borrowed by Michael Jackson, Rihanna (who was sued), Quincy Jones and several others. But O Boso is more than just an album with a worldwide hit, it is for many the most successful album of the late saxophonist’s career. It’s also the one the neophyte should start with to discover the multifaceted musical universe of Dibango. In eight tracks, O Boso offers a multitude of musical styles that defy easy categorization: Afro-folk, jazz-fusion, brassy funk, Afrobeat… Almost 50 years after its release, this record remains a true timeless nugget. (Patrick Baillargeon)

1976: Afrovision

The late Manu Dibango made his mark on the world map of music with the enormously influential 1972 hit “Soul Makossa”, the title of which essentially served as a calling card. While fellow sax-man Fela Kuti, in nearby Nigeria, was refashioning hard American funk with local fuji and highlife into a weapon of political resistance, “the Lion of Cameroon” was applying a lighter touch, or at least more lighthearted – his blend of funk and makossa (a style named from the Duala-language word for “dance”) was cheerful and uncontentious, if often as aggressive and uptempo as Kuti’s jams. Dibango’s sax demanded attention, forcefully, but rewarded it with a hydraulic uplift in the listener’s spirit.

An overview of Dibango’s seven-decade career leaves no question of his constant creative restlessness. 1976’s Afrovision is solid evidence of that – having established his brand with his 1972 hit, this album found him eager to show off his diversity, as well as his capacity for keeping up with current stylistic and production trends.

Obviously, a disco number was de rigueur on any album released in 1976, and so Afrovision kicks off with the sparkling, punchy “Big Blow”. As though to say, “you all got what you came for, now stick around and see where I’m going”, that track is followed by the unexpected, sax-free “Streets of Dakar” with its melodic percussion, mewling slide guitar, and mild, rubbery groove. The energy level spikes again with the dancefloor fillers “Aloko Party” and “Bayam Sell’am”, and then comes “Baobab Sun”, which not only showcased Dibango’s chops at the vibraphone (as does the closing title track), it suggested a strong reorientation towards jazz, which Dibango would take further in the years that followed. (Rupert Bottenberg)

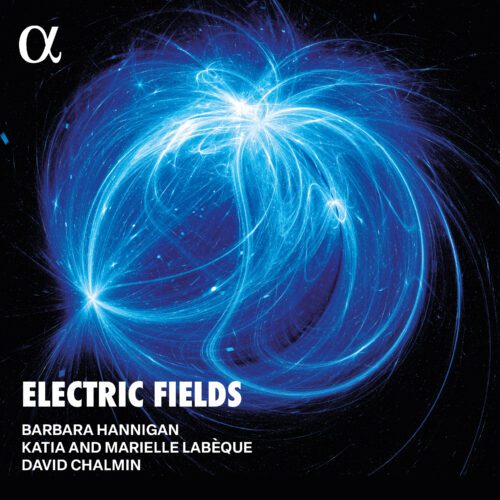

1985: Electric Africa

In the mid-’80s, Herbie Hancock recorded Future Shock and Sound-System, excursions into electro-funk and instrumental hip hop. Miles Davis triggered his latest contemporary funk-jazz eruptions with synths, bass and electric keyboards. Then based in the Paris area, Manu Dibango was into American music, which he adapted to his funk-makossa-bikutsi-jazz. The strength of this groove, the singularity of the breaks and riffs initiated by the tenorman and his huge rhythm section, was taken to the fore. These long, horizontal, irresistible grooves, punctuated by multiple complex asides, were generated under the guidance of Bill Laswell, a visionary producer at the time. Dibango’s extraordinary cohort included Cameroonian bassist Francis Mbappé, Beninese keyboard-player Wally Badarou, American keyboard-player Bernie Worrell and Guinean griot Mory Kanté. All this was capped by the leader’s voice, baritone phrases in Douala, his expressive tenor playing and the female backing vocals. And of course there’s pianist Herbie Hancock’s memorable solo at the heart of the title piece, ten minutes and 28 seconds of pure enjoyment. (Alain Brunet)

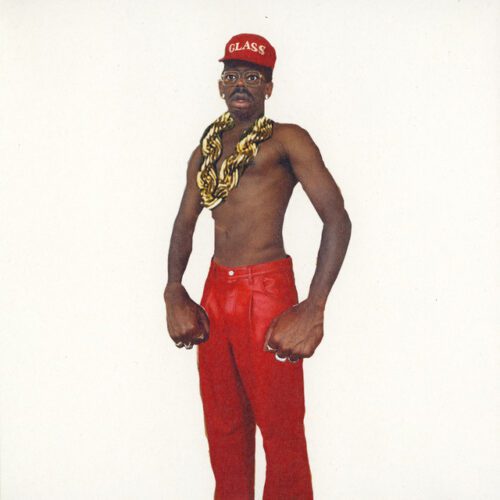

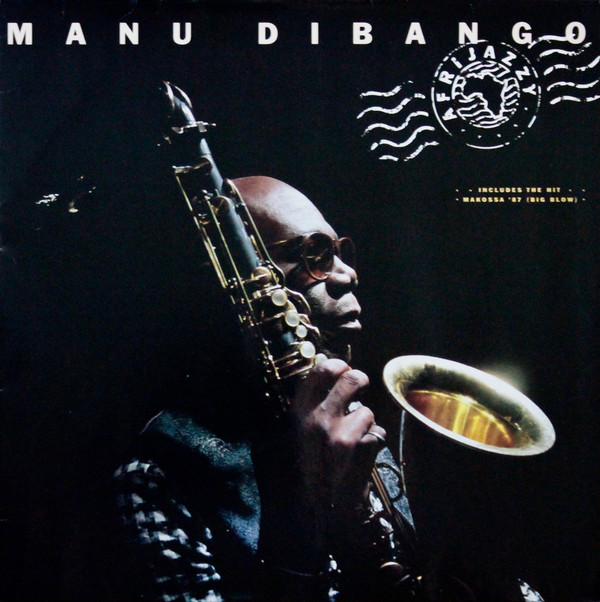

1986: Afrijazzy

Afrijazzy is the culmination of the relationship between Bill Laswell and Manu Dibango. Although he was limited in the articulation and knowledge necessary for high-level jazz, the tenorman had reached exceptional heights in collective performance, comparable to Carlos Santana at the time of his jazz forays (Caravanserai, Welcome, Borboletta). Montreal music lovers remember that Afrijazzy‘s material was played at the Spectrum in the summer of ’86, at the end of a veritable tropical storm that had battered the city. The concert was simply fabulous, although different from the recording released during the same period. Once again produced by Bill Laswell in a New York studio, Afrijazzy‘s repertoire is closer to pan-African music, from Ghanaian highlife to the South African jazz of Abdullah Ibrahim and Hugh Masekela, and the Afrobeat of Fela Anikulapo Kuti. A small army of musicians took part in these historic sessions, even more considerable than the one mobilized for the opus Electric Africa. The powerful makossa-funk infusions re-emerged at the end of the programme, reminding us that Dibango was also a popular-culture musician, and one of his crucial missions was to get asses moving. (Alain Brunet)

1994: Wakafrica

In 1994, Africa’s musical movers and shakers gathered around Manu Dibango to record a summit meeting. The Wakafrika sessions have been held in Paris, London, Los Angeles and New York. Youssou N’Dour (Senegal) covers “Soul Makossa” in Wolof, Salif Keita (Mali) sings on “Emma”, Ray Lema (Congo) on “Homeless”, King Sunny Adé (Nigeria) on “Hi-Life”, Peter Gabriel (in the heyday of Real World) and Geoffrey Oryema (Uganda) on “Biko”, Ladysmith Black Mambazo (South Africa) on “Wimoweh”, Angélique Kidjo (Benin) and Papa Wemba (Congo) on “Ami Oh!”, Bonga (Angola) and Touré Kunda (Senegal) on “Diarabi”, and the list goes on… This is a collective work, fundamentally pan-African, which bears witness to the great currents in vogue a quarter of a century ago (b’balax, makossa, highlife, juju, gospel, zulu, etc.), all arranged, orchestrated and directed by Manu Dibango. The musician had moreover respected the particularities of the styles and cultures of the stars on the programme. In other words, the leadership and unifying power of this giant Cameroonian transplanted to France. (Alain Brunet)