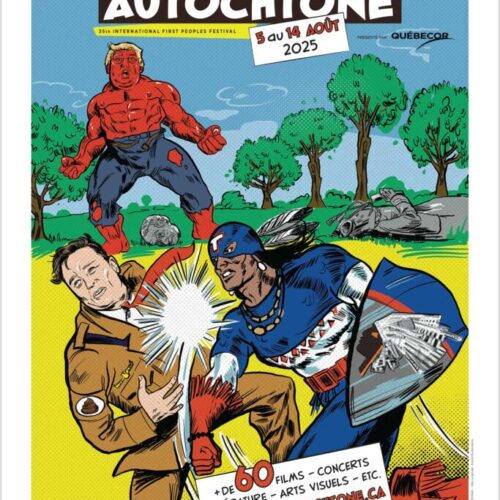

As the audience files into the theatre, a sharp, persistent bell cuts through the room. Off to the side of the stage, Tiziano Cruz crouches in a colourful poncho, waiting. No grand entrance—just presence. A stillness settles. He begins to ring the bell, slowly, deliberately, calling in a flock of sheep across the Andean mountains of his youth. With Wayqeycuna, Cruz doesn’t seek applause—he demands witness. This solo work, part of his autobiographical trilogy, marks a return to his Indigenous community in northern Argentina, where personal memory becomes collective ritual.

“You probably came to see the guy in the colourful clothing. Consume me,” he states, confronting the audience with the gaze they brought with them. Then he speaks of his village, living beside a lithium mine, caught between beauty and exploitation. “I live in a world of white power,” he says, slipping deliberately into a white jumpsuit. Traditional melodies blend with haunting synths and a tender a cappella duet with a village boy, shaping a sonic world that’s both sorrowful and whimsical.

The stage, divided by sheer curtains and bathed in shifting projections of mountains and sea, transforms into both sanctuary and confessional. Cruz doesn’t move like an actor—he inhabits the space as a witness, channeling generational trauma, ancestral strength, and the lingering stain of colonial violence. “The customs officer still views me as a danger, and I wear colourful linens,” he says, voice steady. Through poetic language and striking visual cues, Cruz builds a heartbreaking, fiercely symbolic journey—one where nothing is ornamental, and everything has menaing. Every image in Wayqeycuna carries weight: the recurring wolves as a metaphor for capitalism, the bread and poncho as loaded symbols of both cultural pride and pain.

Cruz avoids spectacle entirely. He summons the Andes with vivid language, revives childhood games through precise gestures, and lays bare systemic oppression with a tense, deliberate stillness. One moment, he soothes with memories of village festivals; the next, he hurls the audience into harsh scenes of poverty, exclusion, missing teeth, and a village engulfed in flames—whether metaphor or memory, the wound is real.

Wayqeycuna—“my brothers” in Quechua—isn’t just a title; it’s a call. A quiet yet urgent invocation for collective memory and solidarity. Midway through, Cruz lifts his phone and snaps a photo of the crowd. It’s a small breach of theatre etiquette, but it hits hard, reversing the gaze, shattering the illusion of passive spectatorship, and implicating us in the frame of oppression. Simply by existing, Wayqeycuna becomes political art—less something to watch, more something to endure.