Like all humans of goodwill, we, music lovers, will have to monitor carefully the consequences of the invasion of Ukraine by the Putin regime.

Instrumentalists, composers, beatmakers, singers, amateurs, connoisseurs, pedagogues, musicologists, producers, and tour organizers will feel something strange… every time a Russian artist will speak in the coming days, months, and years.

What will happen, for example, to the great Russian musicians revered on the classical planet? What will happen to those artists whose careers are essentially based on international influence, especially in Europe and North America? We are thinking here of the pianists Daniil Trifonov, Evgeny Kissin, Denis Matuev, the violinist Maxim Vengerov, and many others.

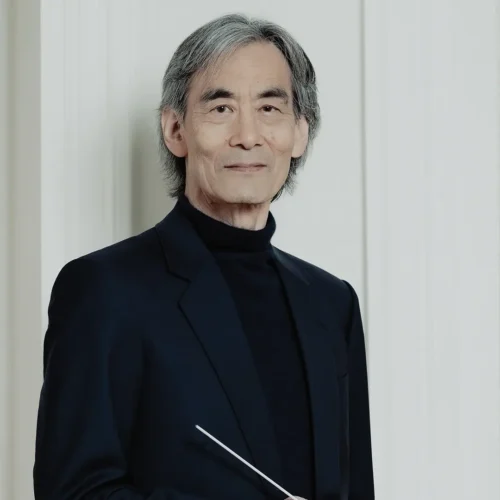

The unease is already setting in this weekend with the replacement of the Russian maestro Valery Gergiev by the Quebecer Yannick Nézet-Séguin at the helm of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. The Austrian orchestra is scheduled to perform in New York for three nights in a row at Carnegie Hall, starting Friday.

For those unfamiliar with classical music, this replacement of Valery Gergiev, an avowed close relation of Vladimir Putin, is a legitimate and justified move, one that makes sense. Those who know the value of the Russian maestro, however, do not have exactly the same reaction: they are upset by the idea that an artist of such talent shares Vladimir Putin’s conquering delirium, a historical fiction turned tragic reality.

Hasn’t Valery Gergiev invited us to the most formidable symphonic programs in recent decades? Don’t orchestras levitate under his direction? Anyone who has attended concerts given by the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra knows what a fabulous maestro he is, and what a fabulous orchestra he directs. I interviewed him a few years ago and can assure you that I have been dealing with a brilliant man, a man who is both coarse and refined, rough and delicate, patriot and citizen of the world, without any doubt one of the great living masters of the Russian repertoire of the Romantic, modern and contemporary periods.

This case is more than interesting, because Valery Gergiev, today shunned by the West, embodies the Russian paradox that artists trained during the Soviet era, pure products of Stalinist authoritarianism of the communist tradition, are living today.

Let’s try to understand.

The conductor is 68 years old, he was educated in the 70s by the best pedagogues of an extremely solid classical culture in the Soviet Union. At the turn of the 1990s, the young maestro was able to count on the support of the mayor of St. Petersburg, Anatoli Sobtchak, and his first deputy, a certain Vladimir Putin, in order to build a new concert hall, which was inaugurated in 2006, and an ultramodern opera house, the Mariinsky II, inaugurated in 2013. Remember that the architect of the building is the Canadian, Jack Diamond, who drew the plans of the Montreal Symphony House (whose construction is very close to that of the Russian amphitheater).

Gergiev knew Putin before his meteoric rise to the top of the Russian state. They were both shaken by the death of the Soviet empire, they witnessed its fall and the instability that followed. And, like so many intellectuals and artists supported by the Soviet regime, Gergiev may have experienced the fragility of his status after the communist era ended… then reinvigorated by the current regime.

A leading artist of the Putin regime, Gergiev has never hidden his friendship and support for the former deputy mayor, a former KGB officer who became president for life of a country described in French as a “democrature” or if you prefer in English “democratorship”, an amalgamation between a surface democracy and a de facto dictatorship. Let’s remember that Valery Gergiev conducted the symphony orchestra at the opening ceremony of the Sochi Games, applauded live by its president for life. So we can guess why Gergiev has already refused to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine … a few years after approving the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Barring a dramatic about-face that would exclude him immediately from his advantageous position in the Russian nomenklatura, the maestro will assume his choices.

This position is understandable, but now unacceptable from a democratic and progressive point of view, after what happened recently. By remaining faithful to his buddy Putin during wartime, in any case, Gergiev risks putting an end to his career in the West. Abruptly. Already dumped by the powerful Felsner Artists agency in Germany, he could be excluded from his responsibilities with the Munich orchestra of which he is the artistic director, his links with the Vienna Philharmonic and other Scala orchestras in Milan could be broken forever.

His performances may now be limited to areas of Russian influence, to markets dominated by the Chinese ally, by the Turkish ally, or other areas where Western culture is in decline. That’s still a lot of people again, you may say. It’s the new world of classical music, you may say. But, losing his fame in the old world will hurt Valery Gergiev a lot. He will pay a high price for the rest of his life.

Let’s assume that this great Russian artist has been thinking about this issue of denouncing the imperialist, authoritarian, and bellicose intentions of the Putin regime. Let us assume that the most outstanding Russian conductor of our time refuses to express any condemnation of the Russian state because he shares its patriotic and conquering values. Let’s assume that he has resigned himself to renounce his Western career.

Let’s assume that he assumes this strange paradox… and that this position draws him to the dark side of the force.