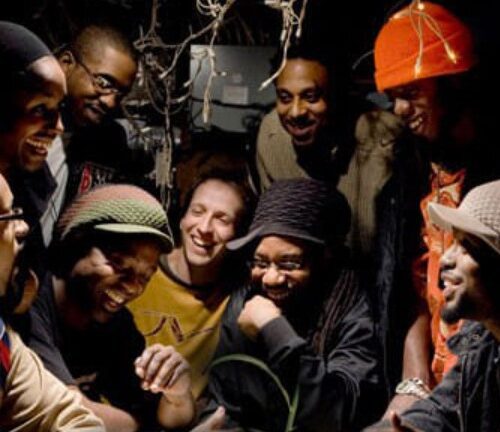

With the Montreal Jazz Festival officially starting on June 26th, the June 25th performance by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra could be seen as something of an opening ceremony. This is somewhat fitting given the ambassadorial stature that Wynton Marsalis and co. have assumed over the years.

From the start of the program it was clear that the repertoire was selected deliberately to allude to the current political climate in the United States – the band began with three notable works of black protest music: Marsalis’ own Black Codes from the Underground, Charles Mingus’ Fables of Faubus, and John Coltrane’s Alabama. The latter was well served by a somewhat minimalist arrangement that left plenty of room for baritone saxophonist Paul Nedzela’s interpretation of Coltrane’s melody. The soft muted chords played by the rest of the horn section contributed to a beautiful and haunting soundscape. The most direct political message, however, came during Fables of Faubus. Trombonists Chris Crenshaw and Vincent Gardner sang Mingus’ original lyrics, which explicitly criticize Nazis, fascism, and the KKK – a poignant sentiment with the current rise of right wing extremism in the US and around the world.

The band went on to showcase compositions by several of its members; Carlos Enriquez, Chris Crenshaw, Elliot Mason, and Vincent Gardner, with a highlight being Crenshaw’s Bearden (The Block). This gospel-influenced piece cycled through several contrasting grooves, while kept grounded by consistent harmonic language. It featured one of the highlights of the set – a tasteful yet understated tenor saxophone solo by Chris Lewis – and finished with a vocal call and response section that had the ensemble gradually getting softer in a way that was reminiscent of a faded ending on a record.

At the tail end of the set there was a warm reception for an interpretation of March Past, the seventh movement from Oscar Peterson’s Canadiana Suite, arranged by Vincent Gardner.

With this year being his centennial, the Montreal crowd were especially keen to show their appreciation for such a local legend, and that energy was matched in the performance. The band then concluded the set with a Gardner original, entitled Up From Down. Marsalis had few words to say about this piece, simply stating, “It’s about these times.” The piece featured plenty of dissonant harmonies and overlapping, discordant rhythms, with brief moments of levity in resolution, which could be taken to illustrate the practice of finding joy during difficult times.

Jazz at Lincoln Center is often the subject of discourse surrounding ‘old vs. new’ debates in jazz, and is often seen as a proponent of the tradition – a comment often levied at Marsalis himself. While there is truth to the sentiment, it feels like a narrow perspective, as the ensemble consistently brings new ideas to the table when playing the music of the late jazz greats. Their renditions of Mingus, Coltrane, and Peterson don’t feel like exhibits in a museum; they are filled with contemporary ideas and interpretations. We see this in the makeup of the band, with several younger musicians mixing in seamlessly with the more established members, emphasizing the importance of keeping one foot in the past and one in the future.