Additional Information

Without helmet and without safety net, the co-founder of Daft Punk has just launched his first large-scale composition for large orchestra, intended for a ballet at the initiative of choreographer Angelin Preljocaj. Mythologies is a work of 23 tableaux performed by the Orchestre National Bordeaux Aquitaine under the direction of Romain Dumas.

His fans should be aware that Thomas Bangalter is far, far from doing Daft Punk. Without any advanced technology except perhaps a composition software, and especially in an orchestral spirit very close to European romanticism in the second half of the 19th century, the French artist revisits in depth his relationship to composition.

This is certainly an excellent subject for an interview… given to us by Thomas Bangalter in a video conference.

PAN M 360 : What brought you to symphonic music? You must have had a good musical upbringing, as is the case in most good families.

THOMAS BANGALTER : It’s not exactly a story of a “good family” in fact, it’s rather a family of artists and classical music came to me through dance: my mother (Thérèse Thoreux) was a classical dancer, my aunt was a dancer, my uncle was a choreographer, my father is an author, composer and producer, so I was born into a family of artists. But my relationship with orchestral music and symphonic music came about through dance, and then, I would even say, through the discovery of symphonic music in the cinema. I did indeed take piano lessons when I was a child, but my piano teacher was a coach for the Paris Opera, but he came from the dance world. But my music wasn’t a sideline, it was quite central. Art was the centre of it all.

PAN M 360 : PAN M 360: In classical dance, anyway, there is necessarily a rather intimate relationship with classical music. Not necessarily. There’s a lot of contemporary music or modern music that are different forms.

THOMAS BANGALTER : Yes, my mother was initially a dancer in a classical company with Roland Petit’s Ballets from the end of the 1950s, for about ten years. Then she joined the first contemporary dance company in France, which had been set up by the Ministry of Culture, called the Ballet Théâtre Contemporain. There, she did contemporary dance and then created music by composers such as Xenakis. There is both this double filiation with classical lyrical music on the one hand and contemporary music on the other.

PAN M 360 : So it’s kind of natural that you would come to this point at some point in your creative career. How did you go about creating this music? The first time you do a cursory listen to this album, it feels like you are in the XIXᵉ century. It is romantic music from Europe, well mostly.

THOMAS BANGALTER : It’s funny because I feel like I didn’t think that much about it. It’s quite a spontaneous approach to this idea of elegance, lyricism or romanticism, which are things that I don’t necessarily see in society today. I often have the impression that I’m thinking by reaction and that I want to bring out things that I miss at a given moment. In 2005, with my partner in Daft Punk (Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo), we had this idea: “Let’s make a pyramid of light and LEDs like this”. It was something we had in our heads, but it didn’t really exist. A few years later, I remember being in Times Square and there were LED walls everywhere – it used to be neon. Now we’re in a world that’s completely covered in LEDs with increasingly huge systems at all levels of scale. So I wouldn’t have the idea today, the idea of saying to myself “Here, I’d like to create a geometric structure in LEDs”. So there is this idea of counterpoint or interaction with one’s environment.

PAN M 360: So what is the motivation for this new “counterpoint”?

THOMAS BANGALTER : A lot of reasons aligned to do this project. At the same time, this dance world that I knew well and from which I had distanced myself a bit, although… it was dance music that I was creating at the time. But then, there was a certain timelessness in the idea of tackling myths. I also like to do things that are a bit old-fashioned. Because in the end, when it’s old-fashioned, it doesn’t really go out of fashion any more! You don’t have a relationship with modernity by trying to create something that, five years later, may sound a bit out of date. I like the idea of tackling forms, making them exercises in style with a certain interest in temporality. It’s true that this idea of romanticism sprang up without being an intellectual thing.

PAN M 360 : Of course, it was not the result of any planning. It wouldn’t be art.

THOMAS BANGALTER : It was much more spontaneous actually. When we were working on Random Access Memories ten years ago, we were in the middle of the EDM boom and this hyper energetic, hyper electronic music. And at that time we had a slightly romantic vision of the dancefloor, a bit of a disco. So there was this idea of having fun with these retro-futuristic codes. Except that this time, I found it funny to arrive in a retro-futurism not from the 70s or 80s, but from a century before, even two centuries for some colours because we could be at the end of the 18th century for some moments even if it’s the end of the 19th century for most of the pieces.

PAN M 360 : When you’re an authentic artist, you don’t say to yourself “I’m going to make music from 1855 to 1890. It’s something that comes out of the subconscious, but you can see that several so-called neo-classical composers are familiar with this romantic period (and also with early modern French music).

THOMAS BANGALTER : What I find interesting is that I don’t find myself in an axis that could oppose, as it has been for contemporary music towards classical music for example. It’s a bit the same thing in pop music today, where many of its barriers have fallen. I worked with samples but also with studio musicians where we wrote the music, the scores or the arrangements completely. So it’s not one method against another. That’s perhaps what’s changing the most at the moment, because before there were chapels that hated each other. Today, the perspectives are really very different. It can be related to certain lyrical or neo-classical colours, but at the same time it can use cells of repetition and get closer to contemporary minimalist trends. So I don’t feel that it’s so contradictory now, whereas there used to be a certain purism in the vision of symphonic music.

PAN M 360 : How did you adapt to symphonic composition?

THOMAS BANGALTER : I had some experience with symphonic music on film scores and other music, but I had worked with orchestrators and arrangers at that time. My main motivation was to take on this project to write for the orchestra and to do all the arrangements and orchestrations myself. I usually compose on the piano, but my lack of virtuosity on the piano would limit the composition a bit. That’s why it was really a music that was written directly on the score with a notation software. At that point, I worked on different sketches that I sent to the choreographer. From there, the concept of mythology became clearer. After that I went to my corner to write most of the music. A few months later I came back with the written ballet. There was a bit of cutting, editing and structural planning with the choreographer, and then, the dancing started.

PAN M 360 : So, no one other than the choreographer was involved in the editing, in the editing of the original score

THOMAS BANGALTER : No, except for the conductor who was also in the process from the beginning. He was able to help me with certain questions. I myself was immersed in symphonic music, in the direction of works. For many months, I really studied the orchestration treatises but… I still had questions that only a conductor’s experience could answer, especially about managing the effort, about the feasibility of certain parts. The conductor was therefore able to guide me on certain questions. I asked him not to give me the solution but rather to tell me more if it was viable. It was really a work with the choreographer and the conductor.

PAN M 360 : So you are free of all the preliminary stages, i.e. without an orchestrator or arranger. This time you were alone, without a net – and without (Daft Punk) helmet needless to say.

THOMAS BANGALTER : That’s it. That was the reason why I accepted this project. I’ve always liked reinventing the circumstances of the creative process. At each stage of Daft Punk, we had the opportunity to approach the work in a different way. When I worked on a Japanese cartoon, it was the same, a bit like an internship; I had been back and forth to Japan 15 times when I got into cartoon production. The opportunity of such a project was a bit like starting from scratch, learning new things, making mistakes and starting over, succeeding in certain things and realising once again that in a state of mind, when you are a beginner, you don’t do the same things in the same way as someone who is really experienced. But this innocence and this sincerity or this clumsiness interests me as a rule. That’s also why I decided to take the time to accomplish this work spread over two and a half years and which must have mobilised me about a year and a half full time.

PAN M 360 : Now if we talk about the concept of Mythologies, how did it finally come about?

THOMAS BANGALTER : The choreographer had the idea. After I gave him some sketches and had a few meetings on those sketches, about twenty minutes at that point, he came back to me and said “I feel like these colours and this direction work with the idea of working on mythologies. That’s when he came back with a list, a kind of compact booklet of different myths. I then started to propose to him the attribution of these different myths to my different sketches. When he validated that, I went back to work on my own.

PAN M 360 : And is there any connection with your background as an electronic composer and producer and what happened in that context?

THOMAS BANGALTER : Not really. If I go back to the last Daft Punk record that we did in Random Access Memory, I don’t really feel like it’s an electronic music record. So I find it hard to answer that question. It’s true that I worked more strictly with machines at the beginning (of my career), but soon enough I made compositions and songs with these machines. And then added (non-electronic) instruments as I went along. I’ve done instrumental music with machines too.

PAN M 360 : This time, not at all.

THOMAS BANGALTER : There was definitely a certain form of radicalism in me saying “I’m going to compose music without a machine, just for the orchestra, for the musicians and to accompany the dancers.” From that point on, it’s true that in this process, there was perhaps not a futuristic determination, but I have the impression that there wasn’t necessarily one in the others either. Where I make the connection is in the idea of trying different forms with each record, which is what I was saying earlier. I’m interested in how the records respond to each other or how the tracks respond to each other. If you take techno tracks and then put in more abstract sounds or even extracts from mythology which can be very lyrical. What amuses me is the contrast.

PAN M 360 :n fact, you are a generalist who wants to get to the bottom of things in each of your projects.

THOMAS BANGALTER : In fact, I don’t feel like I’m saying to myself, “that’s it, now I’m a composer of symphonic music”. These are attempts, explorations, experiments, but what motivates me is to keep on experimenting. The idea of being a bit of a stickler for something, but exploring different forms. Sometimes we try to do… Sometimes we might have the pretension of trying to do things that have never been done by anyone. Sometimes, we can become much more humble, that is to say, we can just have the ambition to do something that we have never done ourselves. For me, it was more like that. So I didn’t really have this idea of saying to myself “I’m going to invent symphonic forms”. It was more like asking myself “If I write with an orchestra, what do I want to express? What will be expressed through this?” Afterwards, there was a functional aspect too. We come back to the idea of making dance music or dance music. It was a music to accompany the dance and to accompany this theme too.

PAN M 360 : This music was written for a ballet, but is it also meant to be independent from the dance?

THOMAS BANGALTER : In the end, I realised that it could be. At the beginning, I wasn’t sure it would be made into a record. I was really trying to do a live show at the time. I was interested in writing and composing for 50 musicians and 20 dancers in a theatre like the Bordeaux Opera or the Théâtre du Châtelet. I liked this slightly local aspect at a time when everything is hyper-connected and hyper-globalised. In the end, when I listened to the music again, I said to myself that it was appropriate to be able to release it as a record, even if it wasn’t the original idea. Getting there was already a big challenge.

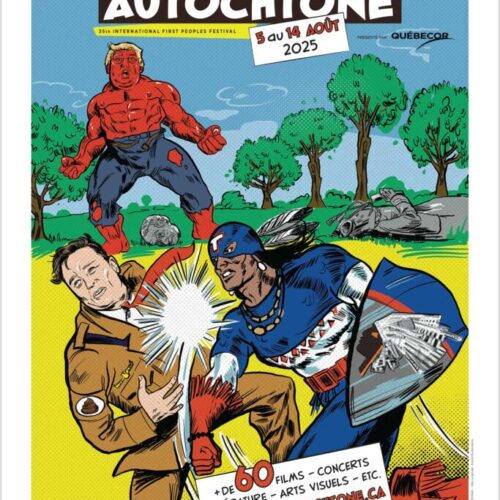

ILLUSTRATION COPYRIGHT: STÉPHANE MANEL