Additional Information

The second floor of Studio TD, the new name given to L’Astral for obvious sponsorship reasons, has been transformed into an atypical museum: under the title “Stranger Than Kindness,” an exhibition devoted to Nick Cave will be presented there as of Friday, April 8.

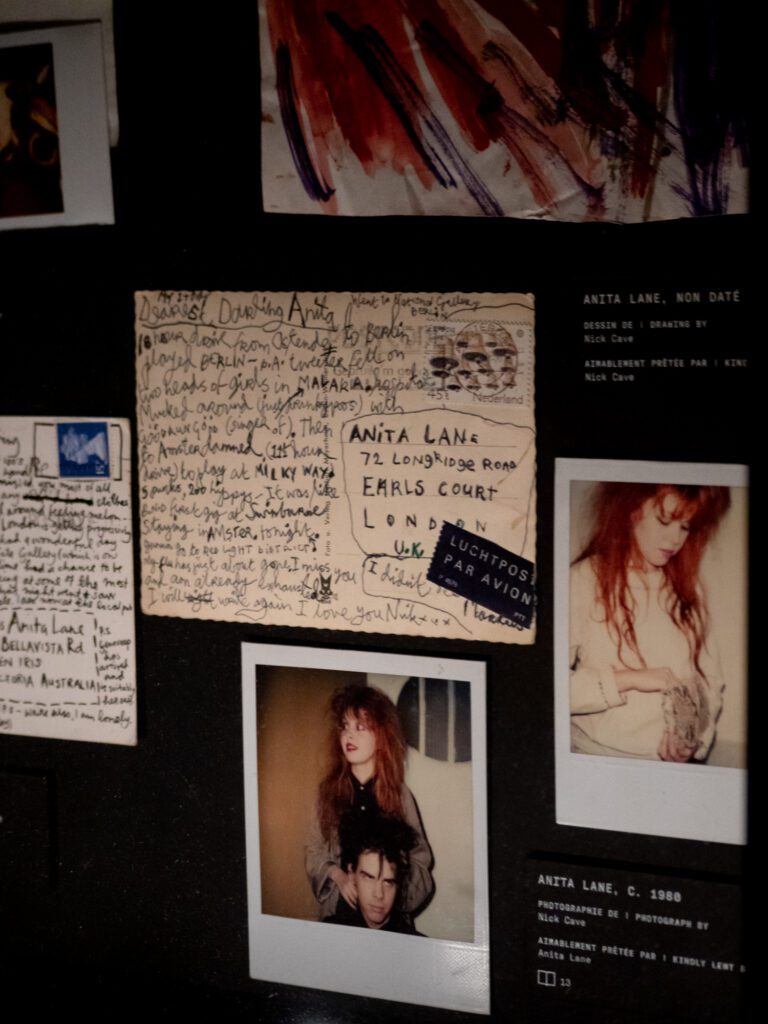

Originally for the Black Diamond, the modern extension of the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen, this exhibition was imagined by curator Christina Back with Nick Cave as co-curator and co-designer. The exhibition features hundreds of objects accumulated or created over six decades. This is a unique foray into the creative world of Nick Cave, this atypical exhibition. Beyond the evocations of the famous artist, we look at what shapes an existence and what builds a human being.

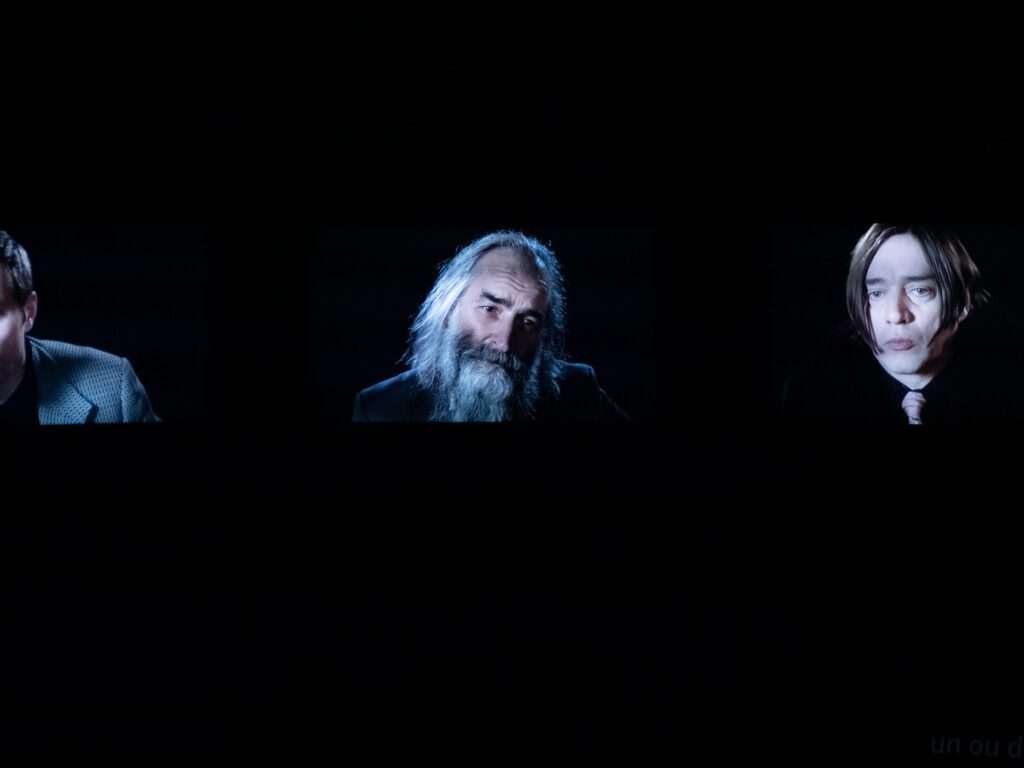

Never before has Montreal experienced such an immersion in the world of the Australian writer and avant-garde rocker, one of the most brilliant of the current era. Since Montrealer Victor Shiffman, who produced the famous Leonard Cohen exhibition, is the producer of this exhibition, Montreal is honored to host the event, which was preceded by a pair of memorable concerts in Salle Wilfrid-Pelletier at Place des Arts last weekend, orchestrated by Warren Ellis and Nick Cave, joined by three backup singers and a multi-instrumentalist.

The aesthetics of Carnage, a record led by Cave and Ellis as a duo, dominated a repertoire that consisted mostly of this 2021 recording and also of Bad Seeds songs written over the past decade under the musical direction of the same Warren Ellis, without whom Nick Cave would not be what he musically is today.

Thus, several Montreal journalists from institutional and independent media (Radio-Canada, CBC, The Gazette, La Presse, PAN M 360, Sors-Tu, etc.) were given a 49-minute and 49-second conversation with Nick Cave, at the heart of the exhibition dedicated to him. Here are most of the quotes, adapted by PAN M 360.

Photo credits: Jérôme Bertrand

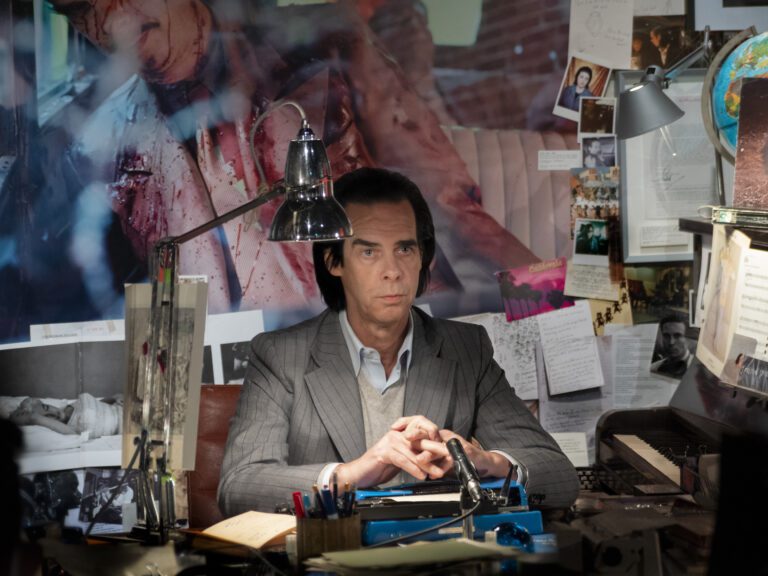

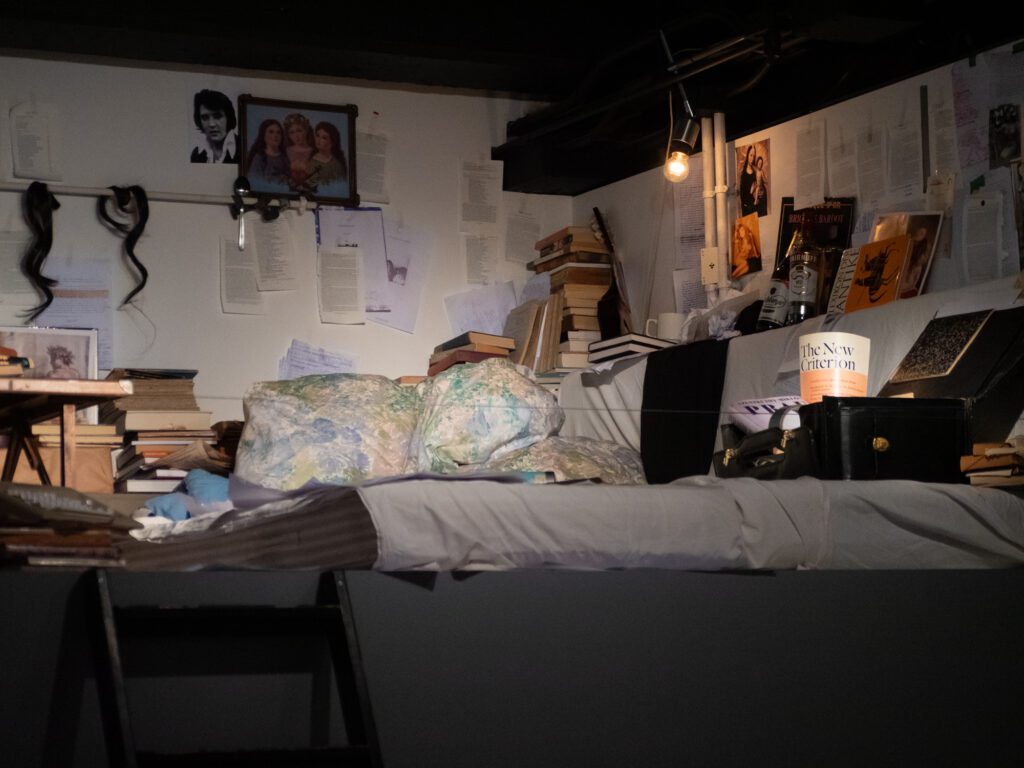

Arrival of Nick Cave in this room illustrating the artist’s office, the photographers do their job:

“What are you doing in my office? Oh, well, take the pictures. Hello everyone, I’m Nick Cave. Hello! And yes, this was our last show of the tour so please excuse me if I seem a little distracted or exhausted… It’s just because I am. So, what do you want to know? Is wearing masks an individual choice or a rule? A rule? It’s a little weird… but I don’t know how it works here.”

On Warren Ellis’ keyboard at the concert:

“I think it’s a $300 synthesizer that Warren found that has a really beautiful sound, an emotional sound, instantly melancholy, but also uplifting. So it’s very hard to get rid of!”

Possible correlation between the repertoire of the Montreal concert and this exhibition, a retrospective repertoire of the last decade and the retrospective of a lifetime:

“I don’t know… For an artist who has made 20 albums or written 250 songs, or whatever, most of the songs were ones we’ve played over the last few years. That’s unusual, I think. What we tried to do was to put on a show that focused on work that was close to today. And so it’s pretty much the last three or four albums.

“But there’s also something that parallels this show, because it’s kind of strange for me to walk through this show, I think it very clearly shows the life of a very self absorbed, creative person who had some kind of violent break in her life or even a series of violent breaks. And this piece that we’re in now is the end of something.

“I didn’t realize, even before I walked through it, that this room was representative of a kind of self-absorption, artistic self-absorption without paying attention to anything else.

“And then you walk through this door behind me, and everything changes, and I think I live on the other side of this door. And sitting here now, it’s, it’s like, there’s a strange sense of disconnection towards that. I think a lot of people, a lot of fans love this period. They like all these things, they like my older music, the older forms of it, the associations of the past, the old Bad Seeds musicians. All that kind of stuff, this show represents that too. But there’s something that happens, beyond my control, when you walk through that door. And it requires me to make a different form of music. And I’m personally very proud that we have continued to follow the truth of things, wherever it may lead. And I think this show is a great reminder that the music is just getting quieter and more thoughtful.”

On the concept and intent of all this work of collecting objects that became an archival project:

“I must have had an idea at the time… Like these things laid out in this room in Berlin, stuff that I obviously valued, like these little books that I made and kept because I just thought they were beautiful. But mostly, it’s piles and piles of junk that Christina (curator of the show) had to go through, and, and radically sort through to find the right ones. So it’s not like I had much to complain about Susie, my wife kept everything. She quietly pulled all my stuff out and put it in storage. So there were storage containers that I wasn’t even really aware of, my wife was more interested in conservation than I was. So these things are from the last 25 years, but these little things in the Berlin room are just little things.

How Nick Cave feels about the physical surroundings of this exhibition dedicated to him:

“There’s a certain sense of detachment, it’s kind of like a museum. But at the same time, there’s been a lot of work done in this room, and in the last few days I’ve been adding new work. And there’s new stuff that I had in my pockets, there’s a Tom Waits letter on my bed that I got a few weeks ago on tour. So this piece feels like a piece that can keep changing as the show goes on. From city to city it can grow, this room that we are in can grow. Because I’ve done more things since then, ceramics for example. Yeah, I mean,And I hope that the last hallway, the gratitude hallway, can grow and be different than it was in Copenhagen (the first city where the exhibition was held.”

On the marked presence of Leonard Cohen in the exhibition, on the impact of the Montreal artist in Nick Cave:

“When I was about 14, in Australia, in this little country town where I grew up (Warracknabeal) and had left to go back in the summer for school vacations, I had a friend who was slightly older than me. She invited me to her house, she made me listen to Songs of Love and Hate in this very dark room, with boxes on the windows. And she told me to listen to what is there in a way, throughout this exhibition, through these re-creations of important moments. We don’t make a big deal about it, but that’s why Leonard Cohen is there on the turntable in the room.”

“I was a weird kid growing up in a country town in Australia, I felt like I didn’t fit in, I didn’t understand the same things as the people in this small country town. Then I heard Avalanche, the first song on this album. It was a seismic shift for me. Suddenly, I felt like someone understood me. That voice became the voice of a friend. That followed me for the rest of my career. You put Leonard Cohen more than others on a guitar neck, there was always the tone of his voice, there was always that feeling of listening to a wise friend. And yeah, that’s why it was a huge moment for me to listen to that song. And to understand that there was something else that was putting words to my own feelings of angst and anger and love.”

On books observed in the square: Nabokov, Dostoevsky and other writers who inspired his work:

“I must say I was blown away by Crime and Punishment. I had studied this book in school, thanks to a great literature teacher who had encouraged me to take a deep dive into this literary pool. It really changed me, it had a huge influence on this idea of living your life outside of what you’re expected to do. And I mean, Raskolnikov (the main character in Crime and Punishment) did it in his own way. For me, as an Australian, there was this idea of living beyond the expectations of others, who were told to shut the fuck up, keep their heads down and not make a fuss. It was a very inspiring book in that regard.

“And yes, these books are the touchstones for all of us from my generation. Important things to hold on to. And that to me is one of the things about this exhibit, I personally feel that it has a duty to convey that information, even though it may not be appreciated in the same way as it was when I was young. Times are changing and people are looking for something else. As I get older, I see myself as a sort of custodian of these valuable items. Letting these things come that people easily forget. It doesn’t take long for someone to be forgotten. You think, “How can anyone forget Leonard Cohen?” But not long ago I was talking to an 18-year-old about the Sex Pistols and he said, “Who?” It doesn’t take long to forget. And so it’s worth it to hang on to this stuff.

“Are you afraid to get forgotten?” someone asks.

“Personally, I don’t really mind in that regard, because I have my own exhibition.”

On the presence of locks of hair among the objects in the exhibit:

“There are these particular locks of hair that I had found at a flea market in Berlin. There were three of them, they were the same length, and sewn together at the top. So one, two or three women, I could never tell, had their hair cut simultaneously. And it gave me endless ideas about what really happened to these women. You know, the character in the book I wrote in Berlin (And the Ass Saw the Angel) also had these locks of hair, they’re very present in the book. Because real life blends into this particular book. So it’s pretty amazing that I was able to keep that hair. In fact, my wife gave me a little drawstring bag with her own hair that she cut off, so I could take it with me on tour. I’m not sure what that means or what she expected me to do with it. Anyway, it’s in my suitcase. (laughs)”

On the addition of a letter he recently received from Tom Waits:

“Anything that comes along, anything that I find, anything that I have or receive that may be of occasional interest can find its way into the exhibition. In this corridor of gratitude, particular things have massive importance, like this note from Leonard Cohen, for example, received after the death of my son: “I am with you, my brother”. That is an extraordinary thing to receive, so simple! It spoke to me more than anything I was told at the time. So everything in this piece has tremendous significance, a reference to Elvis Presley (my primary influence) or this letter from Tom Waits who I’ve never met – I’m going to do that soon in New York, in the context of a memorial for the late producer Hal Willner.”

On the veracity of reproducing real places, on how he works in those real places:

“Actually, it’s almost identical. I had an office like this, I came to the office, I worked in the office, it was separate from the rest of my life. It became something I couldn’t do anymore, because I felt like I couldn’t do it anymore. The artistic sacrifice, sitting there and working on things, that vague idea of your own creative genius, or whatever it is, all the relationships you have that disintegrate because you’re so focused on your work, and you’re never there. I realized that afterwards, I found out that it wasn’t me anymore. There were other things about my work that I thought were more important. So now I don’t work the same way, I still work every day, from morning to night, but I don’t do it the same way, pathologically absorbed in myself.”

On the motivation for bringing all these objects together in an exhibition:

“I can’t really say. It means something, doesn’t it? It says a lot about someone who had a sense of self-importance, maybe that’s a bit of an exaggeration. I don’t know if it’s a joke or if it’s for real. What do you think? “

On the photo of Monica Lewinsky, hanging in the exhibition :

“It was taken by photographer Polly Borland, who is a very good friend of mine and has taken many pictures of me. She took a picture of Monica Lewinsky and gave it to me, and it was on a wall in my office. I don’t know why it’s here but I really like this picture. There is this look on her face…”

On Nick Cave’s decidedly less dark state of mind, observed at the concert as well as in the press conference:

“You know, there’s a lot to be happy about right now, especially for a touring band. Because at this point, we’ve managed to tour England, parts of Europe and North America without getting COVID. In the beginning we toured in a bubble, whereas more recently we haven’t really followed any protocol, we’ve been adjusting as we go along. It’s pretty amazing, actually. No one is going to cover your tour, it’s a very risky business to go on tour these days, but we think it’s a very special time to be on tour. The audience is learning to be an audience again, there’s a certain sense of danger within the audience, sitting there in a group of people in a pandemic. There’s also a joyful aspect to being able to get on stage and make music. Personally, it makes me much happier these days than I’ve ever been. I just found a way to make it happen.

“This happiness was hard-earned, it’s an earned happiness, maybe a suicide. I think it just speaks to the value of things, getting on stage, playing your music, being surrounded by friends and playing in front of people who have come to make you feel like these are special moments, moments of joy. Generally speaking, that’s how I see it these days. I think as I get older, the thing to do is eliminate unnecessary things. Wherever I am it’s a huge privilege to be on stage and perform. That’s how we feel when, like last weekend, we were able to play very emotional, very personal, very intimate, vulnerable shows. And yeah I love seeing what Warren (Ellis) gives us with these beautiful musicians and singers It’s kind of a legacy, it’s really something.”

On what was also taken out from his home:

“A group of Vikings (laughs) came to my house and took everything away, emptied my drawers, took my books, unhooked my paintings from the walls, rolled up the rugs, and it’s all here (in the exhibit). And so, oddly enough, I’ve been accumulating different books lately. There’s not as much fiction, there are other kinds of books, religious books for example.”

On his interest in the sacred, the mystical, the religious, gospel and sacred music in his music, the religious objects and books in the exhibition, on the tension between belief and unbelief:

“Yes, there is a tension. I think it’s in that tension that the spiritual engine of my work exists, it’s at the heart of that tension. What I particularly like about Christianity is that it leaves a lot of room for doubt. And so I see myself essentially as a religious person, although I have serious doubts about some things. But I think I’ve come to a point where I’ve realized that I’ve spent my entire adult life, and even my childhood, struggling with the idea of the existence of God and other related ideas. Finally, it seems to me that this struggle is the religious experience itself. The idea of whether God exists or whether God existed becomes almost a technicality. The religious impulse has always been there, it is everywhere, it is not an occasional phenomenon. I think it’s just getting stronger and stronger.”

On the self-absorbed artist:

“When you’re young, especially when you’re making art, you assume that art is everything. That’s what it’s all about. And the artist’s life is something exalted, the supreme state. And, in fact, everything else suffers as a result, your relationships with your children, with your wife, with your friends or in your civic involvement. I discovered the hard way that there were other things more important to me than the creative experience.

“That doesn’t mean my life doesn’t explode in all directions through my artwork. Creatively, there’s so much going on right now. But I think when you’re on your deathbed, or something like that, that I wrote The Mercy Seat might not be the most important thing you know. When I sit down with my wife, I don’t tell her, honey I wrote The Mercy Seat (laughs). There’s something else, I think. When you walk through the door behind that desk, there’s something else, and that’s what this exhibition is trying to say too.

“Piece by piece, this exhibition represents a series of ruptures: childhood, being sent to the city to go to school, the Berlin years… these are a series of states of being that collapse and wither, and move on to the next. And it supports the idea that nothing feels very stable but…there’s something behind that office door that feels more stable: my family, my wife, my kids, my friends.”

On the distinction between work and the deeper self:

“Creative work has its own life, and it has its own understanding of where it should go. For me personally, the intention is different. I feel like the intention has to consist of a certain gradation. It is beyond myself, beyond a kind of enlargement of my own self within which resides an enormous potential to make things better and to do good for people. I understand that because I understand it for myself; I understand it from art, music and other creative things. It helps me a lot. And I don’t know how to stop there. I’m trying to get a song done before Sunday, Sunday always seems to come so quickly.”