Additional Information

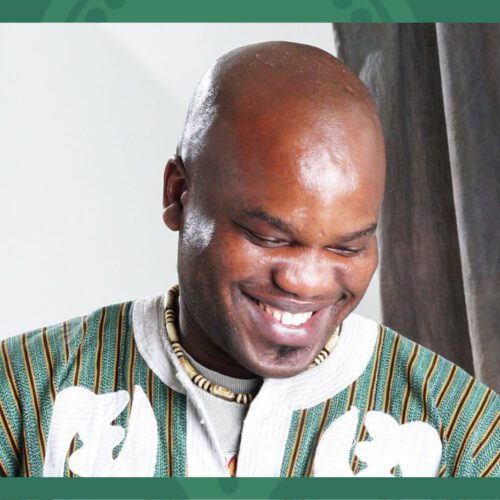

Berlin-based, Roderick Cox was born and raised in Macon, Georgia, a town in the Deep South from where also come Little Richard, Otis Redding to name a few icons of African-American music history. But his destiny is quite different: still, at an early phase of his career, he is becoming an internationally renowned conductor, emerging from a new generation of highly talented classical musicians from all over the world.

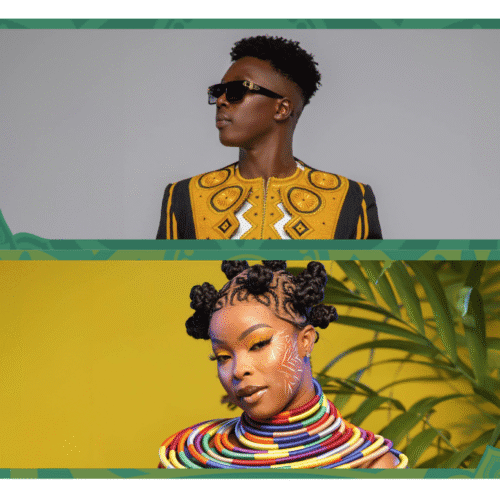

Roderick Cox is a Berlin-based Black American conductor. In 2018 he won the Sir Georg Solti Conductor Award, the largest of its kind for an American conductor. Since he’s been invited by the Boston, Cincinnati, Detroit, Seattle and New World symphonies, Minnesota orchestras, and the Aspen Musical Festival Chamber Orchestra. He has made debuts with the Houston Grand Opera and the San Francisco Opera and recorded Jeannine Tesori’s Blue with the Washington National Opera. Upcoming highlights include debuts with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, and Barcelona Symphony, and his return to the Los Angeles and BBC Philharmonics.

He attended the Schwob School of Music at Columbus State University, then graduated from Northwestern University with a master’s degree in conducting in 2011. At Northwestern he studied conducting with Russian maestro Victor Yampolsky and Mallory Thompson, a master conducting pedagogue. He then studied with Robert Spano at the American Academy of Conducting in Aspen, Colorado. He has also been involved in the project Song of America: A Celebration of Black Music, conceived at Hamburg’s Elbphilarmonie. In that project, he has been leading William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony, which he recorded with the Seattle Symphony Orchestra and will be performed at the Maison symphonique.

In Québec, he was invited for the first time by Orchestre Métropolitain at the Festival International de Lanaudière, in 2018. He was then formerly associate conductor of the Minnesota Orchestra (Osmo Vänskä ). On Thursday, October 12 and Saturday, Oct 14, he was invited by MSO to conduct a program including the famous Barber Violin Concerto featuring the great young Canadian soloist Blake Pouliot and other pieces by Tchaikovsky and the African-American composer William Levi Dawson.

Moreover, Roderick Cox is deeply concerned by the neglect of African American composers, and their lack of representation in music institutions. Actually, a vast majority of music listeners don’t know much about Florence Price, William Grant Still, Amy Beach, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Leslie Dunner…

This is why he will conduct in Montreal the Negro Folk Symphony by African-American composer William Levi Dawson, « a unique fusion of spirituals and post-Romantic symphonic aesthetics, with a few discreet nods to European composers ».

PAN M 360 met him this week, after a rehearsal to talk about this program and his own engagement in the classical world as an African-American conductor.

PAN M 360: In the Deep South where you’re from, how have you become a classical musician?

Roderick Cox: I grew up in Macon, Georgia, and I was very fortunate to be a part of a robust music education program as a young student. And so I was able to be immersed and have the opportunity to be in a musical ensemble quite early. Around eighth or ninth grade, the local band teacher came to my school and let us try out and play different instruments. I was first chosen to be a percussionist.

PAN M 360: Did you have a musical family background?

Roderick Cox: Music was a very important part of my family. Growing up, my mother was a gospel singer, very active in the church. And therefore, it seemed as if music was always playing in our house and in our, you know, on the ride to school or music was just always playing. And of course, Macon, Georgia has such a very rich musical heritage with Otis Redding. Little Richard, etc. Of course, I didn’t meet Otis Redding but I met Little Richard, he would come to our church and sit right in front of me.

PAN M 360: But your path has been totally different from Little Richard and Otis Redding.

Roderick Cox: And so when I went to high school, I continued music, it felt something as to it felt very natural to me. Of course, I didn’t think that I would become a conductor. The idea of this never crossed my mind. But I thought being in the band and being in the orchestra was the coolest thing. And I actually felt when I found out it was a possibility to continue this into college with what I had to determine what I was going to do. I thought I wanted to be a music educator. So I actually have a degree, a degree in music education first with a concentration in French horn, I switched to French horn when I was in high school.

PAN M 360: After high school, you attended Northwestern University (Illinois).

Roderick Cox: Then I studied conducting still with the idea that I would be a professor at a university because my passion was around young people and education. At Northwestern I studied with Mallory Thompson, and I interacted with an orchestral Professor Victor Yampolsky, who was former second violin at the Boston Symphony, escaped Stalin’s Russia, and came over to, with the invitation of Leonard Bernstein. I suppose he sort of planted the seed in my head that perhaps I could make a life as a professional orchestral musician. I still remember him saying to me, you should conduct an orchestra. It was a profound statement that immediately broadened my horizons. And I guess when I made the decision to focus on becoming a professional conductor, I never questioned it again and never turned back.

PAN M 360: Is being an African American musician in the Western classical world becoming a normality?

Roderick Cox: I don’t think it’s a normality in that sense. I mean, I still think that’s a very, very rare occurrence. And, you know, even when thinking about this music that I’m conducting this week, the Negro Folk Symphony, it’s, it’s one of the rare pieces of music that infuses my own cultural background into the classical music idiom. And so a number of the styles, the Ragtime, Jazzy styles that’s in the music, but also African-American folk tunes and spirituals and things that are innately in our culture is on the concert stage. And that feels actually quite, quite natural for me to work on this music.

PAN M 360: But you and your African American colleagues have to be yourself a promotor of Black American legacy in the Western classical world, don’t you?

Roderick Cox: So I think we’re still certainly pushing the barriers here. But still, there are very, very few, maybe a handful of conductors. And when you think about the percentages, in classical music, it still hasn’t shifted that much, perhaps it’s a bit more visual now that we live in a more visual society. When you think back, we had Kathleen Battle, Jessye Norman Leontyne Price, and Shirley Verrett. All of those great singers had a special moment, they were in the spotlight at some of the big houses of the world. But today, I think we have fewer people in those sorts of positions.

PAN M 360: So there’s still much to achieve!

Roderick Cox: So it is not a normality. And if the question is… is it better? I’m not sure. And so I think what’s important and what’s necessary is, is an artist’s career, lifespan has to be cultivated. There still must be opportunities and exposure given to elevate artists through years of engagement to a certain level where they can be at the level of Jessye Norman and Leontyne Price.

But then again, it’s very hard to say, when is it enough? And is there a point in saying that we’ve reached a certain place? I think my motto has just been to every place I go, you know, to focus on connecting with the orchestra and with building those relationships and making great music together. That’s what I want the focus to be on, and anytime one goes to still, when I program this piece, the Dawson Negro folk symphony, sometimes I’m a bit apprehensive because I’m thinking, oh, you know, will the orchestra like it? Will they? Will they think it’s a piece on the program, just because it’s a black composer? Is it some sort of agenda that this piece is there? Or is it you know, is it some sort of diversity, initiative or activity for why this piece is there, but actually, I program only music that I really, I try to program music that I really enjoy and really love. And, and that’s why I programmed this piece, often. This is a piece about the folk music of the United States. And that’s why I think it’s important for us to play it because we don’t have, we don’t have much of that. I think that music has to live and breathe.

PAN M 360: You also have to think about the evolution of its interpretation.

Roderick Cox: Yes, it breeds through performances and different interpretations. And what I find is, every time I do work, even with a new or new orchestra, and even this morning with this particular orchestra, hearing it in this space, the music was speaking to me differently, it was saying different things. And perhaps a little slower here, perhaps a little faster here, perhaps a little heavier here, do you want to be and that’s the beauty of the process of a rehearsal, and, and allowing music like this to breathe. Because as we change, the interpretations change in the orchestras. And so I’m very much even more invigorated and inspired by the work in just the rehearsal we’ve just done and immediately after I was in my dressing room thinking about this, this and perhaps we can do this or perhaps this might not be right. And that’s what music needs. The good. The great masterpieces have been there. Many of them are, are great because they’ve been interpreted and played many many times and have gone through scholarly research and so forth to put them at the forefront of our repertoire.

PAN M 360: And so there’s an interesting tension between letting the musicians breathe with the score while having your own touch as a conductor. How do you see this balance?

Roderick Cox: Well, sometimes when you’re doing a piece for the first time, you have many more question marks than then later. And I think after doing this work a number of times, I have fewer question marks, but I also have a bit of self-assurance of I think, what the music is telling me, that may not be necessarily in the score. And that involves you, as an artist being open and listening to what the music is trying to say and what you feel the music is trying to be. That means if there’s tension building, you know, do you want to speed this up? Or do you want to slow down? How much time do you want to create for this sort of impact moment or climax? What type of colour do you want to create here? And so I think that’s where my personal experience with the work comes into place a bit more in interpreting the music and, with these players also explaining a bit, of what the piece is about and allowing and seeing their interpretation. It’s also revealing, it’s also revealing… a good orchestra will be able to see a phrase or see a line and play a phrase with their ideas of what this music wants to say as well.

PAN M 360: So you’re looking for a fair balance between you and the orchestra.

Roderick Cox: Of course, always, always, there has to be a collaboration.

PAN M 360: Let’s have a few words about the Montreal program.

Roderick Cox: The program is quite romantic in scope. So we start with Tchaikovsky’s The Tempest, which I think is a rather unknown poem here in the same sort of scope as Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet. This is based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest. And of course, it’s the story of a sorcerer on this isolated island in the middle of nowhere, he’s been placed there by his enemies, Italian nobles, who is cursing his enemies by creating a storm to destroy them.

It’s also a story about colonialism because this sorcerer takes over the island. And you have two spirits on the island. And you have the sorcerer who’s trying to destroy these. You also have this beautiful love song where one of the spirits falls in love with one of the noblemen and tries to save him from the darkness of the sorcerers. It’s a gorgeous work, one of my favourite works by Tchaikovsky because I think it also has this sense of impressionistic writing to it, similar to some Debussy work or Mendelssohn, Hebrides overture. I love how he creates this tension in the orchestra. And of course, Tchaikovsky was one of the greatest melodic composers ever, and this is absolutely shown in this work.

PAN M 360: Regarding Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto?

Roderick Cox: This work has been written in the shadows of the World War Two before it broke off. So Barber first started writing this in Paris and abroad in Europe before America came into the war. So he knew the turning of the tide was building in Europe at this time, and he finished the work in the United States.

I think it’s a very intimate work. And sort of a personal confession of the composer his feelings in this music, but you hear very much also the shadows and darkness of the war to come in the work, especially in the second movement. The first movement begins, it’s very picturesque, I think I think of a beautiful summer landscape the way this piece begins, and, and its orchestration is really quite small. You have a piano which creates this, this sense of intimacy and chamber-like, feeling and this music. And, of course, the third movement is just riveting, vigorous, exciting music that I think is fascinating to witness and to hear on the stage.

PAN M 360: Is it your first time with Blake Pouliot?

Roderick Cox: This is my first time with him, but we’ve known each other since we went to the Aspen Music Festival in 2014. So this is our first time actually working professionally together.

PAN M 360: And finally we have this piece from William Levi Dawson.

Roderick Cox: This piece was also written in the 30s, so very much in the time of Barber’s Violin Concerto, and this Dawson piece was one of the three black American symphonies at the time played with major US orchestras – we had William Grant Still, Florence Price and then William Dawson. Out of those three at the time, the Dawson Symphony was the most celebrated, played by the Philadelphia Orchestra in Carnegie Hall with a rousing reception by the critics, and enormous applause after the second movement, which is called Hope in the Night.

What’s beautiful about this work is that it reminds me very much of my own culture and that Black American culture is in the midst of such turmoil, turmoil as slavery you know, 300 years of backbreaking work, where families were displaced or cultures were lost. If you listen to a number of the spirituals and folk tunes from this time, it talks about Moses crossing Egypt, seeking a land where life will be better. And I think that black American folk gave people hope. When you think about gospel music, it’s all talking about the hope for a better tomorrow.

This piece was among the primary themes of the civil rights movement.

And so in the midst of this work, you also have many very exciting, beautiful, celebratory moments. So you can have many of these sorts of dance rhythms reminding this: after slaves finished their backbreaking work, they would often get together in a drum circle around a fire and, and, and clap and stomp their feet and keep their spirits alive. And so they were keeping their spirit hopeful and alive while keeping their body moving. And that’s what I love about this music: because in the midst of darkness, especially the second movement, you’ll hear this very static theme which represents Black children, completely unaware of the situation around them, and represents their naivete and innocence. When you’re a child, you don’t know that you’re black or white. Young black children would be best friends with the slave masters’ children and play in the house, and finally, they have to be told that they are not white. And so you have this happiness that builds until finally, this discord and these shadows come.

The last movement begins in the E flat major, similar to Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony, and the other great works of music, but begins in this key, which represents sun and hopefulness and beauty. And so the last movement is very much celebration and looking into the future.

PAN M 360: So this piece was celebrated at its time. And now we’re bringing it back. It’s been recorded by Yannick Nezet Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra, and you will conduct it with MSO among other orchestras.

Roderick Cox: Absolutely. I mean, it was sort of lost and wasn’t really performed for 90 years. And I discovered it myself during COVID. And really worked with the editors to bring out this new edition.

PAN M 360: History will tell but now we just realized that many composers who became obscure after being celebrated almost a century ago, are coming back in a way. Yes. Because of people like you.

Roderick Cox: Thank you and, of course, others and I mean, and again, It’s important to play the works because a lot of the material, a lot of the time the works aren’t done because they’ve been so poorly managed. They’re still, I mean, this work before a couple of years ago, was hardly readable, badly copied with mistakes. And it took, it takes a lot of work. And it takes a lot of resources for the publishers. I think this Dawson work is one of the great American symphonies written and should be alongside Copeland, Barber, Gershwin, Charles Ives, and John Adams.

It’s so unfortunate that Dawson only wrote one symphony, I would be so interested to hear that we had 4 at least. But I think life circumstances for him, he had to raise a family. He took a teaching job in Tuskegee, where he wrote mostly choral music, which became famous, but the fact that he wrote this lovely symphony at a young age. I would have loved to see his compositional life.

Roderick Cox will conduct the MSO on October 12 and 14. For info and tickets, click HERE.

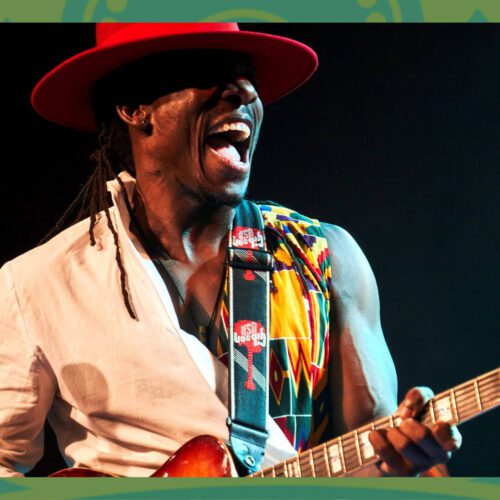

Photo credit : Susie Knoll