Additional Information

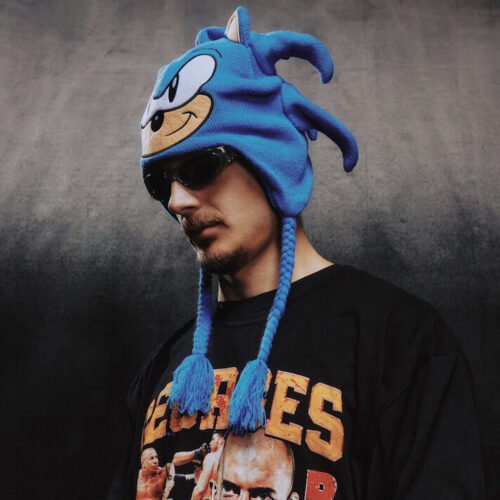

The name Murray A. Lightburn is probably best known as the lead vocalist and main songwriter for The Dears here in Montreal. But his newest solo album, Once Upon A Time In Montreal, deserves it’s own recognition. Inspired by the life of his past father, a jazz musician from Belize who moved to Montreal via New York to reconnect with his teenage sweetheart, Once Upon A Time In Montreal was written by Murray to really put himself in the shoes of his father. His father was married to Murray’s mother for 56 years, until he passed in April 2020 in a Quebec nursing home where he’d been living with Alzheimer’s. Reflecting on the secenario, Murray eventually discovered he didn’t want to make a record about someone dying, but a record that imagined what his father felt, being a working Black man who moved his whole life to be with the love of his life. Murray had to play detective to piece together his father’s story, talking with his mother, and diving deep into his own memories about his experiences with the reserved man.

PAN M 360 spoke to Murray on the patio of Café Olimpico about Once Upon A Time In Montreal, and moving into a newer composing direction, as he did with the film score of the new coming of age cinephile romp, I Like Movies.

“Everything I do, I want it to have a relatability,” Murray tells me while sipping on an espresso. “I was thinking about the whole premise for this album on the way over here and it was that my dad moved here, for a woman, not entirely wanting to be here. He just wanted to be with her. And so I think about how many millions of people get together in that way. They move because somebody has an opportunity. And they’re willing to support that. And be with that. They don’t want to let go of the idea of that. That’s the part that I hope people get.”

PAN M 360: Right. So more of his story living in Montreal, through your words?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: Yeah. You know, part of the story is OK, my dad died. People die. That’s no big deal. He was old and vulnerable. There was no other way this was gonna go right? At the start of the pandemic, it was like ‘OK, he’s gone.’ So I didn’t want to make a record that was about somebody dying, or worse, my grief over that person dying. I wanted to make something that was true to his story and his story, while unique, is also very common. I remember realizing that when we went to the cemetery when the stone was finally up. I hadn’t been to a cemetery is ages. So we went to the stone to say some things, ’cause we didn’t get to go to the funeral.

PAN M 360: Yes, the pandemic wouldn’t allow that.

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: Yeah, just my mom was allowed to go while the rest of the family, about 30 to 40 of us, were on a conference call listening to the play by play. It was brutal. Me and my family and sitting in the living room on speakerphone just listening to ‘Okay, they’re putting him in the ground now.’ And then somebody prayed. It was like listening to a funeral on the radio and that’s not that’s not what I wanted to write or sing about. It’s part of the story but I wanted a bit more of a eulogy y’know?

PAN M 360: And writing this story for the album, learning these stories about your father, would you say it brought you closer to him? You’re singing from his perspective in a few songs?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: Yes. That being said, the perspective is imagined. I’m imagining that if he could find it in himself, to reveal himself, in some way, on his way out, this is what he would have to say. You do what you can you do. I’m not in therapy (laughs). Like he sculpted his entire life around being with my mom, right? It informed everything. And that’s the only thing that actually makes sense about him. And it’s the only thing that I can, aside from the music because he was a musician and all that, really relate to him. I wish we could have had that conversation. Instead, you know, I had to do my own detective work.

PAN M 360: Music is kind of its own form of cathartic therapy though? You write a song to get a feeling out that maybe you didn’t know was there?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: True, but it didn’t intentionally start out that way. I wasn’t really given a chance to get into it, let’s just say. Waiting for him to go, even before the pandemic, whenever he got a cold or the flu, it was just touch and go. Then he would come back and we would laugh, like ‘Nothing can take this guy down.’ Then when it happened, it was so fast. Like when you have a car accident, there’s this whole protocol, and this whole mechanism goes into place. Replacing the car, the police report, this that … I hate to make the comparison, but that’s the only other comparison I can come up with is like there are a whole bunch of things you got to do.

When somebody dies, and is close to you, and everything falls on your lap. Calling the government, getting the death certificate, dealing with the funeral home. There’s a song on the album called “No New Deaths Today.” That actually came from a headline I read months after he died. The sun was shining and I read that and was like ‘This is how we’re being optimistic now?’ I started to see the comedic aspects of it all.

PAN M 360: Of death in general you mean?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: Yeah just the situation, or at least mine. There was a point where I had a situation where the casket that they had picked out you know, in classic Montreal fashion was in on backorder or something like that. They didn’t have his casket at the time of his passing. So I had to negotiate this situation. And his casket originally had prayer hands on it. Well, they were all out of prayer hands caskets. Like this is on the the eve of them putting him in the ground. This was weird to have to deal with. Like you’re in the fog of him being dead and they’re out of the casket that was chosen. So we got stuck with the Virgin Mary on the casket. There’s a line in the song [No New Deaths Today] “no praying hands will wipe our tears away,” which is a sad line, but for me, it’s from my super dry sense of dark comedy.

PAN M 360: The first time I listened to the album, it really reminded me of the old 50s and 60s jazz crooner records. Like Nat King Cole or something. And I thought, there aren’t many records made like this anymore; that have a story from beginning to end, that traditional way of making a record.

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: I think I hear what you’re saying. And I think that’s also something that is still important to me, and I hope that will other artists will challenge themselves to create or to stick with certain traditions of songwriting. I think there’s still lots of real estate to create things that tell stories in a meaningful way. Because there’s a million stories, man, a million fucking stories. And I think that every story has unique twists and turns. But, you know, battling the sort of machine of how the business is evolving, it’s really focused on the shortest gains, the shortest short term gains. The right volume of business, that’s what all it’s about. It’s kind of like the dollar store where you can just walk into the dollar store and get as much rubbish as you can for 20 bucks. And then, none of it lasts. It’s all going either in the recycling or just in the garbage or in the ocean one day—it’s just total disposable nonsense.

PAN M 360: That’s the streaming age for sure.

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: Yes, but I think there’s still an audience for people who hunt for something a bit more meaningful. And dare I say, artisan, boutique-y. I think there’s an appetite for it. Unfortunately, it gets completely tsunamied the fuck out by the sort of dollar store of the current music biz.

PAN M 360: Did your dad play music around the house at all? Did you guys listen to music as a family?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: I mean, I have so many memories of music being played in the basement. My dad had a stereo system that he really loved and put a lot of time into and had everything from eight tracks to reel to reel tapes to records, cassettes. I remember hearing lots of music all the time. You know?

PAN M 360: Did you ever talk about music together? He was a saxophonist and you were learning to play music?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: He never wanted any of us to go into music. He discouraged music. But at the same time, when we showed interest, he did step up and be like, ‘Okay, you want to play drums? Alright, I’m gonna send you to Jimmy Charles.’ He’s a drummer. Jimmy Charles was a guy he played with, a jazz guy, so I went to see Jimmy Charles, when I was like, 12, or 13 got lessons from Jimmy Charles. I kind of was just finding my way through music, and every once in awhile he would step in a be like ‘It’s more like this’ you got to do it like this. I guess I do have memories of my dad teaching me, you know, the melody for “Round Midnight,” which I can’t remember now. I was playing guitar and he would play a line and I would play it back on the guitar.

PAN M 360: And you were writing music too as a kid?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: Yeah. We had this old sequencing keyboard in the living room and nobody played it ever, except me. I would just sit there with my headphones, and just spent the entire day sitting there and I would compose on that. It had so limited memory. I mean, this is like the ’80s. So every time I made something, I had to record it onto a cassette before I could wipe it and do something new. I had just a bunch of cassettes of pieces of music that I was working on. From when I was like, 14 or 15, or something like that. My dad heard some of it. And, you know, some of the pieces were pretty complicated, and very thought out and had all the parts and everything. Like when I hear music it’s usually everything, all the melodies and parts, like this nightmare cloud of music. Now I’ve learned to weed through the noise and focus on the important bits and sculpt form there. But my dad, he was funny because in the face of all that, he knew I was also not a very good musician. Like, I’m actually a terrible musician. I’m not a good pianist, the worst piano player you’ll ever come across, mostly just out of not practicing, right? I have all the ideas in my head, I can make some chords, I can play some, but I’m a terrible piano player. I’m a terrible guitar player. I used to be okay, when I was really playing a lot. And now I don’t have any skills at all. I’m just not a strong musician. My old man, his favourite musician of all time was John Coltrane. So he knew I would never hit that level. And he would say, ‘Well, you’re not much of a player, but you’re definitely a composer.’ And that really stuck in there.

PAN M 360: That wasn’t discouraging to hear as a kid?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: No it wasn’t a negative thing. I was just like, ‘He’s right. I’m gonna focus on that.’ And that’s what I did. That’s what I spent my life’s work doing—focusing way more on the composition of work. You can always find a million ringers to play whatever you want. There’s tons of guys that can just play anything. And people spend their lives practicing and playing. So it’s like, man, there’s already somebody that can play it. Why do I want to play it? I’m focused on telling everybody what to play (laughs). I mean, if I could just compose music, get people to play it. That’s like my dream. And so I’m moving heavily in that direction.

PAN M 360: Composing. Like with doing the score for I Like Movies. So you want to do more of that?

MURRAY A. LIGHTBURN: I do, I do because I find that it’s the biggest part of me in the pie chart of me. It’s the biggest part. Being a performer is not something that I really ever liked (laughs). I’ve never had the desire to be like in the spotlight in that way. I do appreciate being recognized for my work, and not being completely ignored for my work, but only as it pertains to being included in consideration for other work. I don’t want to be excluded.