Additional Information

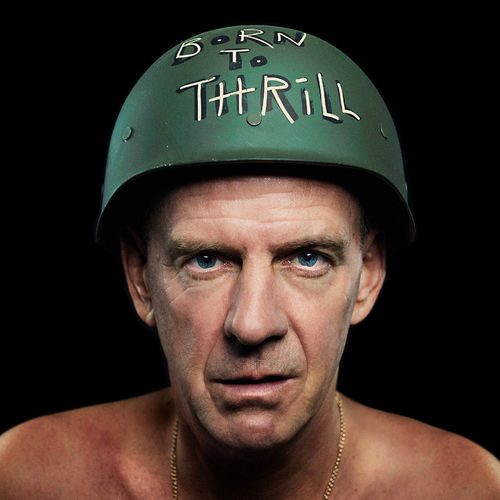

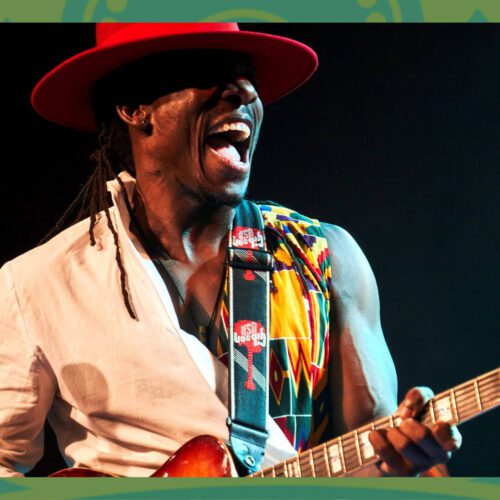

Although we don’t hear as much about him today as we did twenty or even thirty years ago, Fatboy Slim’s name is undoubtedly linked to the beginnings of the rave epic. Hits such as “Rockafeller Skank,” “Praise You” and “Right Here Right Now,” all three from his second album You’ve Come A Long Way Baby (1998), made the DJ and producer known worldwide.

From his early days with the indie band Housemartins to the present day, through Beats International, Freak Power, Mighty Dub Katz and his popular alias Fatboy Slim, Norman Cook’s career has been as impressive as it has been eclectic, and that’s part of the reason his name is still around today.

Inactive on record since 2004, Fatboy Slim continues to travel the world, displaying his musical knowledge and technical prowess from party to party, to the delight of old and young ravers alike.

On the eve of his highly anticipated appearance at the MEG festival–he was supposed to perform at last winter’s aborted Igloofest–, we spoke to the famous DJ who talked at length about his journey, the music that marked him, the beginnings of the Fatboy Slim epic, the big beat, his passion for Djing, the Woodstock 99 disaster, the place of irony in his work and the intoxicating chaos of the party.

Check it out now, the funk soul brother!

PAN M 360: What were your first kicks in music, what did you start with? Remember what was your first album?

Norman Cook: I used to love pop music when I was young. I remember at the age of 8 telling my parents that I wanted to be a pop star. And that’s where I was heading until punk came along. Then I didn’t want to be a pop star, I just wanted to be part of the music world, without being a star. I remember the first record I bought was Suzi Quatro’s Devil Gate Drive… I then learned to play some instruments and it was when I discovered punk that I got into it and started playing in bands. I became a DJ a bit by accident; I was buying a lot of records at the time and they would invite me to parties to play them. So at these teenage parties, someone would often spill their drink or throw up on my records. So at one point, a friend invited me to her party and asked me to bring my records. I said I would come, but without my records. So the friend in question offered to rent turntables and asked me to be in charge of the music for the whole evening so that I would be the only one handling the records. And that’s how I started. I also realized that I liked to share my appreciation of certain songs with others. I liked to play songs and try to guess what people would like to hear next, to create a kind of performance. That’s how I started, I must have been 14 or 15 years old.

PAN M 360: And what did you play at that time?

Norman Cook: I was playing punk rock! It was towards the end of punk and the beginning of new wave… That and some of the pop hits at the time. And it was also during that period that I discovered electronic music, bands like Human League, Heaven 17, and all that stuff associated with the new romantic movement. A friend of mine and I had bought two turntables and in order to break even we used to do weddings, school parties, and I even DJed funerals…

PAN M 360: You actually witnessed this incredible period in British music.

Norman Cook: Yes, I consider myself very lucky to have been able to experience that. For me, it was the golden age of music. Being my age, I’ve seen and heard a lot of it. I grew up with 70’s pop, then punk-rock, hip-hop, electronic music… I think I still have the basic spirit of punk rock, which is not to follow the established order, not to follow the rules, to change things, and to do it yourself. I got more seriously into Djing when I was old enough to go to nightclubs. By then I was playing funk, electronic music, rare groove, and then house. It was really exciting to go to clubs at that time. But it was more of a hobby to be a DJ during that period. We got ridiculous fees. So I played in bands during the day and at night I was a DJ, if I didn’t have a show with one of my bands.

PAN M 360: You played in a few bands and, of course, the Housemartins. I’ve always been intrigued by the difference between the music you played with that indie-rock band at the time and what you turned to afterward. Because after the Housemartins disappeared, you made a name for yourself with Beats International, then after Pizzaman, Mighty Dub Kats, things completely opposite to the Housemartins. Were you tired of playing in bands?

Norman Cook: I was a white kid in a suburb in the South of England and all the music I really liked was black music, like funk, hip-hop, house. During that period I felt that playing black music when you’re white was not okay. There were very few white bands playing black music at that time. So I turned to white indie music with the Housemartins, a band that came from punk. But as a DJ, I didn’t mind playing black music. Then came drum machines and samplers and from then on white people could make music similar to black music without pretending to be black themselves. So that’s what I did, and I dropped the Housemartins. To be honest, I never really liked playing with the Housemartins. It was Paul (Heaton)’s band and I was just the bass player.

PAN M 360: In these other adventures before becoming Fat Boy Slim, you also reveal your love for reggae and dub.

Norman Cook: Yeah, I play a lot of that as a DJ too. It’s the most authentic black music I grew up with. Where I lived, there was always reggae music around me, so I grew up loving that music. But then again, I didn’t want to be that white guy trying out reggae. As soon as samplers came along, you could put all these influences, ideas and different sounds or rhythms into a song and add your own personal touch without pretending to be black.

PAN M 360: So how did the Fat Boy Slim saga begin?

Norman Cook: I continued to play with bands while DJing. There was Beats International and Freak Power, which was a kind of acid funk band. But after about ten years of playing in bands by day and DJing at night, I realized that more people came to see me for my DJ sets than for the gigs of the bands I was playing with. Fatboy Slim was one of my many DJ projects. There was Mighty Dub Katz, Pizzaman and I played with Freak Power. So the last thing I wanted was another project. With Fatboy Slim, it was a way of combining all these different influences into one entity: the catchiness of pop music, the rhythms of hip-hop and the energy of acid-house became a sound of its own, which we called big beat. It all quickly became more and more important in my professional life and I no longer had time to play in bands, I was still up from the night before because of Fatboy Slim. Over the years, I made Fatboy Slim just me, no longer pretending to be a bass player trying to write traditional songs, with lyrics, choruses, verses… The punk rocker in me gave up all that. It was a chance for me to finally create the music I really like, mixing all these samples, instead of making the music I thought I should make.

PAN M 360: For me, the Big Beat sound was a sort of mix between the energy and aggressiveness of punk and the groove of hip-hop, with the added bonus of dub madness.

Norman Cook: Yes, it is! That’s kind of what I like about music. I like the rebellious side of punk and the idea that you don’t have to be a musician to make a record, mixed with the grooves of black music that I like but with a certain pop sensibility. I didn’t want to be too much of an underground artist, I like to entertain people and that penchant for entertainment came across in my sets, where I would jump around, where I could play hip-hop tracks on 45s and techno tracks on LPs, just to fuck with the genres. And with the samplers, the big beat allowed me to keep doing that.

PAN M 360: How did the big beat evolve, if at all, and what is the big beat today?

Norman Cook: The thing is, the big beat never really evolved. It was more of a rule-breaking, genre-bending thing. The only common link from record to record, or artist to artist, was that there was a big beat. Then it became a genre, then a formula and soon everyone started making big beat albums that all sounded the same, and that’s what killed the big beat in a way. It was only a matter of three or four years. But I think the genre still has a place. If you think about it, garage came from the Paradise Garage in NYC, house came from the Warehouse club in Chicago and big beat came from my club in Brighton, the Big Beat Boutique. I’m really proud of that.

PAN M 360: You have all these wacky aliases (Margaret Scratcher, Chimp McGarvey, Son of Wilmot, Yum Yum Head Food… over twenty!), funny song or album titles… To what extent would you say that humor or irony is an integral part of your work?

Norman Cook: I think it’s a huge part of my work. The irony, more than the humor. I don’t make comedy records but I do like to twist things around. Also, I don’t take myself too seriously. There are a lot of musicians who think they’re a gift to the world from God, but I’m just an idiot who likes to show off; I like to make people smile, make them dance. I’ve never seen Djing as a high art form and I’ve never seen myself as a genius artist or a sex symbol… It’s just me making records. And by not taking myself seriously, I think it’s harder for people to criticize me. But also, there’s a huge amount of emotion and reference in music and humor is often an aspect that gets overlooked. As I said, my job is to make people dance and smile, not necessarily to educate them, to start a rebellion, or anything like that. It’s often just about empathy or sex. For me, Fatboy Slim is all aspects of my personality rolled into one.

PAN M 360: Your last album, Palookaville, was released in 2004… almost 20 years ago. Do you plan to release another one sooner or later?

Fatboy Slim: Not really. I don’t seem to like making albums anymore. I did a few and then I just didn’t want to do it anymore. I lost that passion but I didn’t lose the passion to play music for people. But who knows, maybe one day I’ll get tired of going around the world DJing and staying up until indecent hours and I’ll get the urge to make an album again. Never say never, but to be honest, the concept of an album seems a bit stale in this streaming age. I might put out a few new songs, but once I’ve released enough to put it on an album, it’s going to feel redundant.

PAN M 360: Maybe then you’ll bring out your old bass…

Norman Cook: Yes, I still play bass from time to time, for birthdays and weddings. If my friends put a band together for one of these occasions, I’m always the designated bass player! I still enjoy it but I consider myself a better DJ than a bass player, I can assure you!

PAN M 360: What have you been doing lately? Any new projects in the pipeline?

Norman Cook: We recently celebrated the 20th anniversary of the big party we did in Brighton Beach, which was really exciting. Also, I’ve finished organizing my first festival where we take over a holiday camp for a weekend. It’s one of those huge British holiday camps that nobody goes to in the winter. So I’ve selected 35 DJs to take turns at the All Back To Minehead festival weekend. Minehead is a tiny seaside resort in the West of England.

PAN M 360: How do you work on your DJ sets? Do you follow a certain strict pattern with some room for improvisation or do you just let yourself go, following the mood?

Norman Cook: I go with the flow. I know what the first three and last three songs of my set are but what happens in between depends on the crowd, the mood… On the other hand for the big shows, I take fewer risks. People are there to hear the hits. The smaller the show, the more fun I have and the more freedom I give myself. I play with Serato, my laptop, and CDJs.

PAN M 360: A lot of people saw you recently in the documentary about the Woodstock 99 disaster. Was that the most chaotic event you’ve been to as an artist or have there been worse ones?

Norman Cook: Oh no, it wasn’t the worst (laughs). It was chaotic but I wasn’t there on Sunday when things started to get really bad. It was just too big an event. It was full of drunken American kids and when you have that many of them in one place, it can become a problem. But I’ve been to gigs that were far less organized than Woodstock, and gigs where the behavior was far worse and I was really more scared! That will be the subject of another documentary perhaps…

PAN M 360: Could you mention one?

Norman Cook: Um… no (laughs). A gentleman never kisses and tells.

PAN M 360: You said in the documentary that you like chaos when you perform, is it still the case? And what kind of chaos are you referring to?

Norman Cook: I like chaos because dance music is mainly about uniting people but also freeing them for a few hours to forget their stress and boring lives. People are free, people are together, people are sexy and I try to make them forget about the daily train by putting them in a fantasy world full of bright lights, loud music, and solidarity. As long as there is a community spirit, as long as people don’t hurt each other or break anything, I like the chaos you feel when they lose their minds. You feel it and you can see it in their eyes. You see some of them look at you and seem to say “what the hell are you doing here?” and I look at them like “yeah this is fun, let’s go”… For me it’s really exciting because I’m the one who controls that energy, I’m the one who tries to make them go crazier and crazier and they totally lose themselves in the music. That’s the kind of surrender I’m trying to get. I’m not trying to cause a riot, I want the crowd to lose themselves and let go together. That’s the kind of chaos I like and seek when people go crazy, but stay within the bounds of decency and public safety. The crowd is as important as the DJ. If you’re in a band, you can put on an amazing show for a shitty crowd, but as a DJ, it’s a conversation you’re having with your audience. If the crowd doesn’t respond to what you say, then it becomes a monologue.

PAN M 360: Do you play your hits (“Rockafeller Skank,” “Praise You,” “Weapon Of Choice”) in all your sets? Do you sometimes feel like the Rolling Stones, obliged to play “Satisfaction” at every show?

Norman Cook: I actually play Satisfaction mixed with “Rockafeller Skank”! I don’t mind that at all! I would say I play “Right Here Right Now” and “Praise You” quite a bit all the time, but I have so many different versions and mashups and remixes of those songs that I never get bored. I think these are probably the two songs that the public would be disappointed not to hear. “Rockafeller Skank” is not always included in my set though, only if I think people deserve it…

PAN M 360: Do you have anything to say to the people who will attend your show in Montreal?

Norman Cook: First of all to apologize to the Montrealers for taking so long to come, to thank them for their indulgence. Then to invite people to come and get lost in a collective euphoria, to escape… and not to forget their dancing shoes!

FATBOY SLIM PLAYS THE “OFF PIKNIC” THIS SATURDAY, SEPT. 3 AT 4 P.M. BUY YOUR TICKETS HERE!