Additional Information

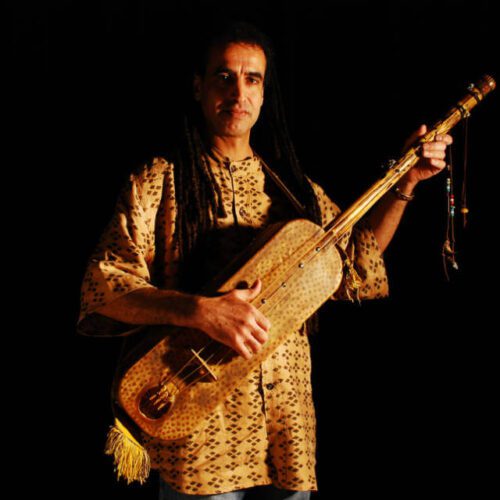

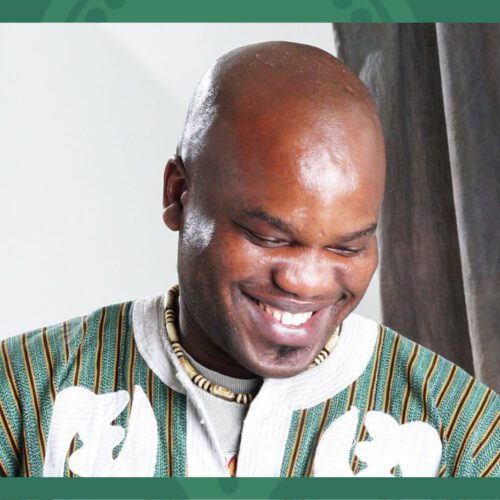

Of Cree descent, (Fisher River First Nation) Toronto-based artist is an visionary composer/conductor/singer/sound designer. We can observe his talent through a large body of choral, instrumental, electro-acoustic and orchestral works.

His work has been performed by the Winnipeg, Regina and Toronto Symphony Orchestras, Tafelmusik, Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, Ensemble Caprice, Groundswell, the Winnipeg Jazz Orchestra, the Winnipeg Singers, the Kingston Chamber Choir and Camerata Nova, Luminous Voices, Chronos Vocal Ensemble, among others.

His choral works, the core of his approach, bring the listeners to gather their souls in a communion, as in Vision Chant, inspired by an Indigenous singing style that reaches the heights of tranquility and intensity.

“Notinikew” , which means Going to war in the cree language, is about Indigenous soldiers who fought for Canada in Europe during the First World War and were denied their rights and freedoms when back home. This anti-war mini-opera evocates « the words and woes of a community and destiny too rarely heard about ».

On his way to Montreal, Andrew Balfour answers PAN M 360 questions about Notinikew.

PAN M 360 : The narrative of your piece is First World War and involvement of indigenous Canadian soldiers. How come this specific episode of Indigenous people history ?

ANDREW BALFOUR : Indigenous people in Canada fought in every war since pretty much 1812 to Afghanistan. So, but originally, the piece “Notinikew” that I wrote, which was more focused on the soldiers that went to fight World War One. And the sort of like that was, you know, that was a long journey if you’re from northern Canada, and then you have to go down to the south to get trained. And then you have to take a train to Toronto, and then from Toronto to Halifax, and then get in a boat and go all the way to Europe and then fight in this war. It’s a pretty big journey. Yeah. I understand that. And it’s also, I think, just the fact that many Indigenous soldiers were quite good at being snipers. There were a lot of really good snipers from indigenous people.

PAN M 360 : But it was quite a tough journey for them, considering the racism in the process added to the already tragic war conditions.

ANDREW BALFOUR : The thing is, for the first two years, Indigenous soldiers weren’t allowed to fight in this war.. a little bit of racism in the army. But halfway through the war, when the Allies realized that they were losing a lot of men, they thought maybe indigenous would be good. Because they’re good outdoors people, they may be good with a rifle on the battle field… So then, several 1000s of indigenous soldiers signed up, hoping that they might be able to get rights when they come back to Canada, which was not the case. Indigenous people couldn’t vote until 1963. So it took a long time for them to get even basic rights.

PAN M 360 : Where does it lead us?

ANDREW BALFOUR : This is more of an anti war piece as well, like for all people. Like, I’m very happy that we’re being involved to bring it to Montreal.

PAN M 360 : But the bottom line is the music itself, and your work. So as an Indigenous composer, but at the same time, you’re not taught you’re linked to to sort of a global aesthetic, that is not only a native, you know, you mix your own legacy and the world legacy. So you have a double training in a way, you’re very close to your traditions, to your cultural legacy ans also you have a classical music training. How do you link those two worlds?

ANDREW BALFOUR : Well, I must admit that I’m not that close to my tradition, because I was taken away from my tradition when I was a baby child. I learned through music because I learned how to read music when I was a young boy in choirs, which is the reason I’m here right now. But I guess we could say I was colonized at a very early age; I didn’t know my language, I still don’t know my Cree, my connections, my medicines, and I must learn much more about my music. I’m able to try to find all those elements that I’ve lost. So I’m trying to find myself through music as much as I try to find my history, my storytelling, my traditions.

PAN M 360 : Then how do you connect with your Indigenous cultural legacy, considering that you are also a musician trained with occidental references ?

ANDREW BALFOUR : Here in North America, we have some of the oldest musical languages in the world. It’s been going on for so long ! We’ve been telling stories, we didn’t write it down for us but it’s very diverse. We know Ontario or Quebec traditions but there so many others in the Americas, from Mexico to Arizona. So many Nations, so different ways of drumming, chanting, playing instruments. So exciting because it’s still here after the settlers wanted to wipe it all out. So we’re still, we’re still singing, but also this hybrid of coming, bringing together like Western music with indigenous music, and yeah, well, no, I don’t really necessarily write traditional indigenous music at all.

PAN M 360 : Now we’re facing a global blend of cultures, respecting our own legacies of course, our own personal traditions, but at the same time, embracing the world. And this is what you do through your music.

ANDREW BALFOUR : I totally agree. Because we need to go forward. But I’d like to see is a little more respect when it comes to Indigenous land and culture. Going back to “Notinikew”, there wasn’t respect, Indigenous men came back from the war, they were scarred. Some of them lost their, their families, their culture, their language, they didn’t get the benefits they were promised. They even couldn’t leave their little reserve. Many of them turned to alcohol or drugs. They were lost and it affected their families and the families of their children. So it’s not a nice story in some ways, it’s just the way that society treats, and so still treats indigenous people wrong.

PAN M 360 : Fortunately, we’re living a sort of Indigenous culture renaissance in the Americas, especially in Canada, almost everywhere in this country. It’s so interesting to see this new energy.

ANDREW BALFOUR : Yeah, and it’s an honor to be doing this festival. That wouldn’t have happened even 20 years ago ! So it’s a great honor. But it’s also a great responsibility, and that’s why we’re working really hard. I live in Toronto now but our group in Winnipeg rehearsed carefully. And so we’re going to do the show in Winnipeg, on the 28th, and before this show we come down to Montréal and present it at the Maison symphonique on the 24th. It’s really exciting !

PAN M 360 : Have you performed the piece before?

ANDREW BALFOUR : We did it in 2018 because 2018 was the100th anniversary of the armistice of World War One. Also a group in Edmonton just did this last November, after what I did some extra editings and other small improvements. So this will be the third time it’s been performed, I’m really looking forward to it.

PAN M 360 : If we can be more specific about the body of work itself, how did you you built that piece? How did you imagine it ?

ANDREW BALFOUR : It’s a cross between the music which is historical inquiry. It’s a mixture of sort of abstract ideas about what we know and the feeling of being there. Can you imagine if you were in a state of trance, and you’ve never been seen war before, some people are firing at you, artillery, mustard gas and all that ? It would be horrifying .

PAN M 360 : Absolutely. This World War 1st was a huge carnage.

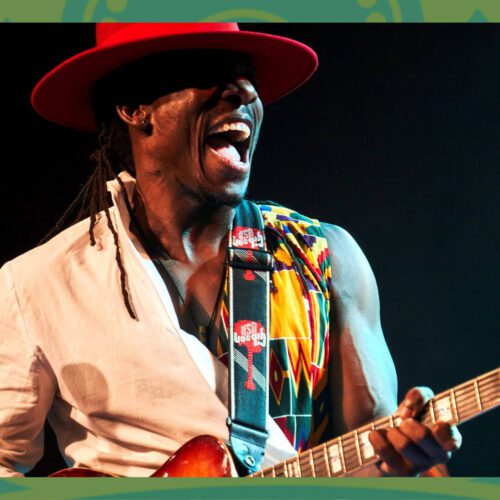

ANDREW BALFOUR : It was insanity in a lot of ways. I think political leaders lost their minds when they’ve been throwing their young men into this carnage, as you said. So there’s also a narration in the piece, and I’ll be doing the narration. And it’s about sort of, like sort of being a sniper lost in the reality of war. And along with a cello player who’s hooked up to loop pedals, and doing some great stuff while helping up the narration. It’s very unique. And we also have a choir that’s going to embody the voice of the youth. In some ways, the music is like a carnage suit, there’s so much going on. It’s hard to explain, but there’s a lot going on.

PAN M 360 : So you work with a small instrumentation with some loops, some electronic machines mixed with modern or traditional instrumentation. And so you mix electronics with a choral approach. So you started as a choir boy, trained like that. So the singing and the choral is basic, very substantial as well as very, very important in your body of work.

ANDREW BALFOUR : Yeah, that’s mostly what I do. I do a lot of orchestral stuff, too. But my most satisfying part is the choir. And they’ve been doing it for a long time. So I still feel like I love the sound of voices coming together. But at the same time, I think it’s the best way to tell a story.

PAN M 360 : Yeah, the voice is the first instrument ever.

ANDREW BALFOUR : Yep. Exactly. And it was my first instrument because I learned how to sing when I was like seven years old. So it’s part of who I am. So I’m very lucky to be able to write in this medium, and I’m very happy to be able to work with some really good choirs.

PAN M 360 : Yeah, at the same time, you have a polyphonic approach, which is not existing in the traditional indigenous music in Canada. So it’s a sort of interesting cross pollination between, you know, Occidental influx and your own rich tradition of storytelling and singing. But it’s not only monadic in early forms of pow wow singing. You’re not working that way.

ANDREW BALFOUR : It’s this because the way I was brought up was the Western culture. But honestly I still love Early Music and Baroque, I sang a lot of Renaissance music. So there was a lot of Early Music that still influences my music now.

PAN M 360 : We also like to think that early music and Renaissance and baroque can fit very well with indigenous music.

ANDREW BALFOUR : Yes. I think it works really well. And, you know, I’ve been doing it for a while now. And I will continue to do it. But I think that, yeah, I’m pretty lucky because I do feel that I do have, you know, still more stories to tell. And right now, Nitinikew is an important story for all of us.

AT MONTREAL / NEW MUSICS FESTIVAL, NOTINIKEW IS PERFORMED AT THE MAISON SYMPHONIQUE IN MONTREAL, FRIDAY FEBRUARY 24TH, 7 PM

Participants

- Andrew Balfour, narration

- Cory Campbell, Ojibway songkeeper

- Leanne Zacharias, cello

- Nolan Kehler, tenor

- John Anderson, bass

- Dead of Winter, 14 singers

- The Winnipeg Boys’ Choir, 6 trebles

- Mel Braun, conductor

Program

- Honour, 2:00Cory Campbell / Cory Campbellvoice and hand drum

- Omaabiindig (2003, 20), 5:00Andrew Balfour

- Vision Chant (2014), 4:00Andrew Balfour

- Domine Deus (Missa Brevis) (2005), 3:00Andrew Balfour

- Travelling Song, 2:00Cory Campbell / Cory Campbellvoice and hand drum

- Trapped in Stone (2017), 5:00Andrew Balfour / Andrew Balfour

- Notinikew (2018), 30:00Andrew Balfour, Traditional / Wilfred Owentenor, bass, treble chorus, chorus and cello

- Opening SongTraditional

- Calling all okihcitâwakAndrew Balfourchorus and cello

- Notinikew [movement]Andrew Balfourchorus and cello

- Sniper’s DreamAndrew Balfournarrator and cello

- I went to warAndrew Balfourtenor, chorus and cello

- Pôni-pimâtisiwinAndrew Balfourchorus and cello

- NimosômAndrew Balfournarrator

- Nôhkom help meAndrew Balfourtenor, chorus and cello

- SongTraditional

- Anthem for doomed youthAndrew Balfour / Wilfred Owenchorus

- OkihcitâwakAndrew Balfournarrator

- WîtaskîwinAndrew Balfourtenor, bass, chorus and cello

- KâkîcihiwêwinAndrew Balfourtenor, chorus and cello

- Closing SongTraditional