Additional Information

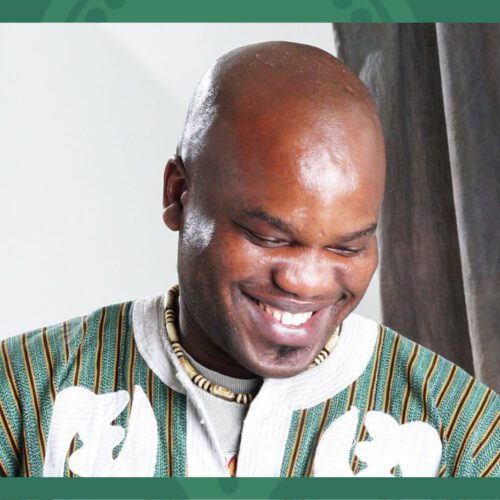

Photo credit: Gaetan Tracqui

Adventures in Foam (1996), Bricolage (1997), Permutation (1998), Supermodified (2000), Out From Out Where (2002)… it’s already a long time ago that Amon Tobin was flirting with old Gene Krupa-style hard swing recordings and other treasures of modern American jazz, coated with hip hop, breakbeat, drum & bass and jungle. This period coincided with an extended stay in Montreal and the rise of the English label Ninja Tune.

Preceded by Foley Room in 2007, ISAM (“Invented Sound Applied to Music”) was released in May 2011. The music on the program revealed important mutations, namely the use of new techniques intended for the production of synthetic sounds and associated with film music. This new aesthetic has been associated with innovative audiovisual performances, the fusion of music and mapping, and has been applauded at all the major festivals of digital arts and electronic music, including MUTEK, Sonar and Moogfest.

In 2015, he launched Dark Jovian, inspired by space exploration. Under the Two Fingers name, he also released the Six Rhythms EP. In 2019, Tobin founded the Nomark label and released an eighth studio album under his own name, Fear in a Handful of Dust. In October of the same year, six months later, he released his ninth album, Long Stories, largely made with an omnichord.

Released under the Two Fingers banner, the album Fight! Fight! Fight! is the pretext for the conversation, but we’re soon enough talking about six different and interrelated projects. Fear in a Handful of Dust and Long Stories, both on Nomark, 2019. Time To Run (Nomark, 2019), as Only Child Tyrant, Six Rhythms EP (Division, 2015) and Fight! Fight! Fight! (Nomark, 2020) as Two Fingers. Figuroa will make its own debut on Nomark in the coming months, with other aliases such as Paperboy and Stone Giants also making their debuts.

“Each one has their own aesthetic. Some came out under my own name. The most recent is based on catchy rhythms that could be compared to the freshest music from some of my early albums, that is, before I took a more experimental direction at the end of the previous decade. The energy and spontaneity of that time was captured and developed into a full-fledged entity of its own, with surprises added along the way, including the use of the human voice.”

It must be deduced that Tobin has not been idle, while some people associate him with an increasingly distant past.

“So there was a lot of activity, a gestation period where I developed something, doing new things that I didn’t know about, it was really intense. I didn’t want to immediately put something in place, I wanted to develop. It took shape gradually, because it was very new to me. I needed to learn before I did, and then do it again until it was good. Yes, it took time! But it’s good, I’m really happy with the result. Last year was the busiest year I’ve ever had.”

Listening to Tobin’s brand new music, it is clear that it’s both autonomous and interdependent:

“The idea is to put different things in specific lanes so that they can all develop in parallel, and they can also inform each other. Something I learn by recording a Two Fingers track will influence something in an Amon Tobin track, something I left in an Amon Tobin track will influence an Only Child Tyrant track, and so on. Then I hope to be able to feed these different projects as they grow. Nevertheless, these projects all have one thing in common, they are created with the same tools, it’s electronic music.”

Tobin’s fascination with the notion of imperfection follows a sequence in which almost obsessive perfectionism prevailed.

“At the time of the ISAM album,” he recalls, “I worked in a very technical way, in order to clarify my proposal. To achieve this very precise goal, I cut out everything that didn’t contribute to it, even if it was a nice idea. Anything that didn’t serve my purpose was excluded. It took a lot of discipline to reach a kind of end point in this process. One of the consequences of this approach was the loss of spontaneity and excitement resulting from the mistake. Because we can learn a lot from our mistakes in creation, we can have a more rewarding experience from a creative point of view.

“Hence the importance of imperfection. For me, it’s important to let this feeling of imperfection return to my artistic process. I want to welcome these things I didn’t expect, let them be born, let them live, and let spontaneity express itself in the music.”

It’s not a question of favouring the unpredictable, he notes.

“There must be a balance between random imperfection and the organization of sounds. You can’t expect to discover things from the air either, it can generate pointless music. But if the structure allows for a certain freedom, then you can reach the balance with useful elements that serve one form and also allow for reproduction in other forms. My recent music is the result of this approach.”

What are the genres found in Tobin’s recent discography? His is a multipolar and extremely diversified approach; several genres are involved, from ambient to techno through krautrock and more conceptual electroacoustics. For his part, our interviewee refuses to clearly identify the sources.

“I’m not overly concerned with musical genres, nor with the language used to describe music. If, as an artist, you are interested in the genres in the music you make, you may be more interested in an external image of yourself. This may be important when you are young, because you need to build a strong image of yourself. Over time, this becomes less and less important. Instead, it is important to feel and identify what you like. So I listen to all kinds of music created by all kinds of artists. Good music is good music, it’s in small quantities and there’s bad music in all genres… what’s the point of concentrating on it?”

One thing is certain, Amon Tobin is an artist in perpetual transformation. What he offered us in the ’90s has been constantly changing ever since. For him, the only constant is… change.

“Change,” he says, “is perpetuated by the artists but their fans are generally opposed to it. You know, this tension is understandable because artists also produce commodities, and their audiences like to understand and embrace what they consume. But my compositions don’t take the listener into account at the time of their conception. If the work is well done, however, I can change the tastes and interests of their listeners.”