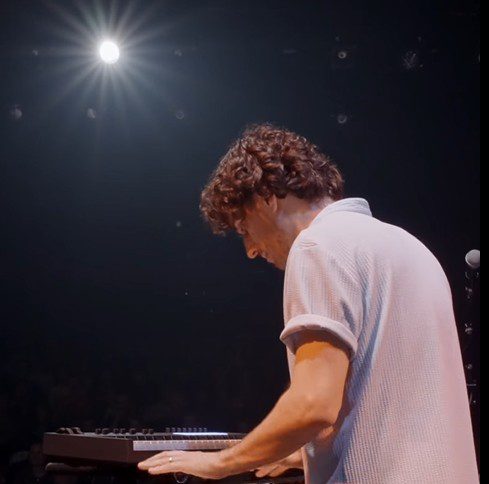

Montreal artist Nicolas Dupuis, better known by the moniker Anomalie, has been releasing music for over a decade now. He is known in the local scene for his infectious beats and virtuosic keyboard playing, and has collaborated with notable artists across multiple genres, such as Chromeo, Polyphia, and Rob Araujo.

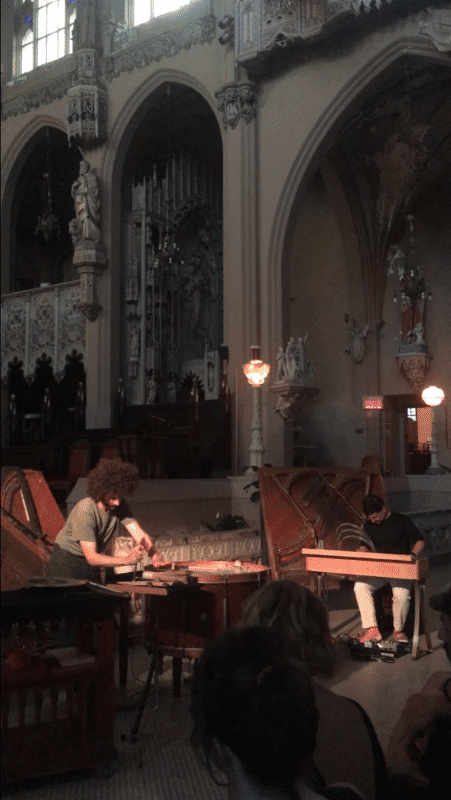

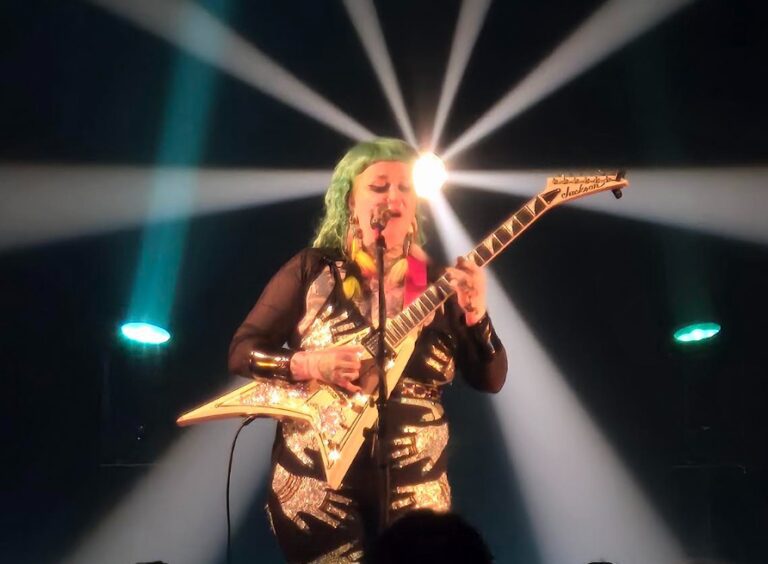

During the Montreal Jazz Festival this year, however, he brought a new type of performance to the stage: fully improvised sets of music. Having already performed a set with drummer Larnell Lewis on the second night of the festival, he took to Gesù again on July 2nd with guitarist Mark Lettieri, famously of Snarky Puppy, and his longtime collaborator Ronny Desinor on drums.

Before the music started, it was confirmed that this evening would mark just the second time the two would play together in any capacity (certainly the first time in a trio with Desinor), which presented the audience with the unique opportunity to watch a new musical friendship between two heavyweights take shape in real time.

The start of the set seemed to have an emphasis on improvising pieces that felt like fully formed songs. Members of the band took turns starting tunes, each time jumping in headfirst with a fully formed groove, chord progression, or bassline. They exchanged solos and came up with bridges to their pieces that did well to drive the music forward. There were points in the set where one could be forgiven for not having realized that the music hadn’t been written beforehand. While undoubtedly an impressive feat, this did come off as somewhat safe at times. The music could have used more space for spontaneity, as Dupuis, Lettieri, and Desinor were at times more loyal to their initial ideas than was necessary.

By the end of the set however, it was clear that a deeper sense of familiarity was brewing. The band gradually started taking more risks with their ideas, and didn’t seem in as much of a hurry to fill empty sonic space. This resulted in pieces that would gradually change over their duration and end in completely different places than where they began. One particular passage that illustrated this shift in approach was a vamp the group settled into towards the end of the set. Centered around a repeated keyboard motif, the vamp grew for a few minutes and approached a strong climax, before suddenly shifting into a double time feel and gradually decaying for a period. When the section seemed to have ended, it slowly shifted into something completely new without the music ever stopping.

While the start of the set could be called safe, this was clearly less of a conscious decision and more so a product of the new setting the musicians had entered. It made it all the more interesting to see how different the band as a unit sounded by the end. While Anomalie and Mark Lettieri both impressed, it should be said that Ronny Desinor’s undeniable presence at the kit was also central to plenty of interesting musical developments. Given a week’s residency in this setting, the group would be sure to open up new worlds for themselves.