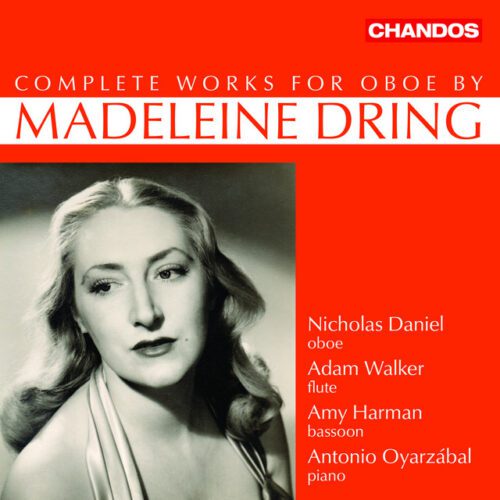

Two years after a musical encounter that was described as masterful, French violist Antoine Tamestit, considered one of the world’s finest, returned to the Quebec stage with Les Violons du Roy. Presented on Thursday evening in Quebec City, this same concert, which took place on Friday evening at Salle Bourgie, featured themes such as death, loss and departure: themes which, despite their dark side, are nonetheless necessary to address, and in which we can nonetheless find light and a form of humanity.

Without preamble, once the orchestra and Tamestit had taken the stage, the hall was plunged into darkness, with the only source of light the lamps on the musicians’ lecterns. This set the stage perfectly for the first piece of the concert, Johann Sebastian Bach’s chorale Für deinen Thron ich tret’ich hiermit [Lord, here I stand before your throne], arranged for strings. According to Antoine Tamestit, in his speech following this short piece by Bach, he wanted to create a sensory experience in which the audience and musicians were led to feel the music through their breathing, through the intrinsic energies of the movement of the musical lines. The moment was indeed soothing, with a sound that was relentlessly gentle, yet rich in harmonies and low tones. The soloist, who also acted as conductor for the first part, followed with Paul Hindemith’s Trauermusik for viola and strings, composed a few hours after the death of King George V. We then enter another universe and harmonic language, with varied textures and musical materials, ending with a quotation from the same Bach chorale.

Tamestit then invited the audience to take part in an aural treasure hunt with Benjamin Britten’s Lachrymae, in which the composer quotes, in the form of variations, the song by Elizabethan composer John Dowland, If my complaints could passions move. To provide context, he performed the original in an arrangement of his own, preceded by the beautiful Flow my tears. A particularly touching moment, in which Tamestit’s sensitive playing came to the fore as the strings accompanied him in pizzicato. In Britten’s piece, Tamestit invited listeners to try and spot the musical extracts of these Renaissance songs scattered throughout Britten’s work. There was a strong appeal to pique listeners’ attention and invite them to open their ears wide to this universe of sound. His interpretation of the musical lines, with their enveloping thickness of sound and pure, fleshy grain, showed an invested and sensitive musicality. It has to be said, however, that Britten won the game of musical hide-and-seek, with Dowland’s excerpts remaining difficult to identify, even for seasoned ears.

The pièce de résistance of the concert was Tamestit’s arrangement for string orchestra of Johannes Brahms’ String Quintet in G major. For this final piece, in which Antoine Tamestit joins the viola section, we were treated to a blaze of emotions and luminous vivacity, particularly in the first and last movements, while the central movements – Adagio and Un poco allegretto – flirted with Hungarian folk accents and melancholy affects respectively. In this new texture with its increased sound amplitude, playing with 21 instrumentalists together without a conductor is a challenge that Les Violons du Roy met with brio and aplomb, producing a particularly rousing and gripping result, especially in the last movement, which is extremely dance-like with gypsy inflections.

The warm ovation from the audience and the radiant smiles on the musicians’ faces made this second collaboration between Antoine Tamestit and Les Violons du Roy well worth repeating. Having begun in darkness and contemplation, the concert ended in great light and human energy. Bringing out the beauty of a program that traces in filigree the themes of death and loss is not in itself innovative. But in this program, imbued with a skilful organicity, where we are naturally transported from one state of mind to another, we are reminded that even in the darkest moments, we can find beauty. To quote Félix Leclerc: “C’est grand la mort, c’est plein de vie dedans.”

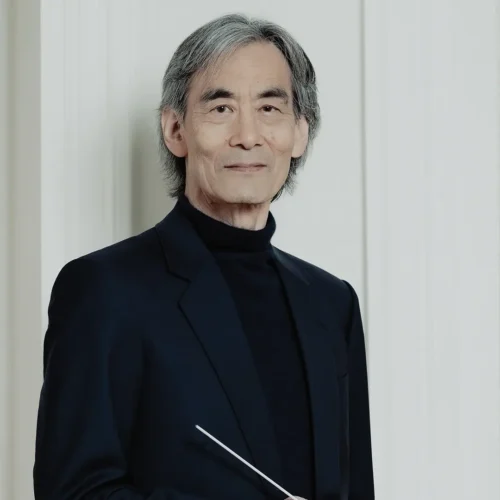

Photo Credit : Pierre Langlois