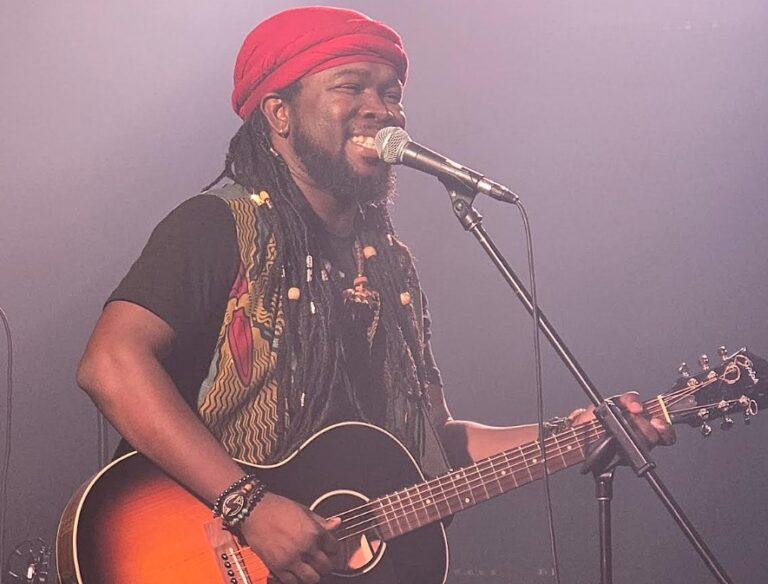

Part of Montreal’s Brazilian community was eagerly awaiting Mateus Vidal, ex-singer and percussionist of the legendary Salvador da Bahia band Olodum, on the free outdoor Nuits d’Afrique stage at the Espace tranquille. Except that the intense thunderstorms of this torrid late afternoon delayed the show and put the crowd to the test.

Mateus Vidal now lives in Montreal with his family. He has set up a new band called Axé Expérience, which mixes axé music with samba-reggae. Both genres were popularized in the 80s, blending samba, African percussion and Jamaican beats. These rhythms have been dubbed “Afro-Brazilian”, hence their rightful presence at Nuits d’Afrique.

Mateus Vidal was undaunted by the elements. With his section of three percussionists, accompanied by a bassist, a keyboardist, a guitarist and a saxophonist-flautist, he took to the stage, singing and jumping. After ten minutes, the sun came out, only to disappear under the rain after another 10 minutes.

It was a magical moment, despite the inclement weather: as Mateus Vidal moved from one side of the stage to the other, dozens of umbrellas did the same choreography. Others continued to dance under large umbrellas, or in the open air despite the rain.

The sparse audience was overwhelmingly Brazilian, of all generations. Smiles abounded, despite the circumstances. Still, I’d like to question the Festival’s decision to program an Afro-Brazilian celebrity at 5pm, for one hour. But festival programming is always unpredictable.

Mateus Vidal aimed for a broad musical spectrum, covering hits such as Gilberto Gil’s Bahia, in samba-reggae mode, and pieces by Olodum, among others.

Then the jinx set in again: the sound system broke down. No problem: the band continued with percussion only, bringing back the sun and creating another magical moment.

Magic and the unexpected! Sometimes it works. We can only hope that the new Montrealer and his new band will be able to take advantage of a better window of opportunity, so that people here, Brazilians or not, can get to know him better and dance to his music.

Photo Credit: André Rival