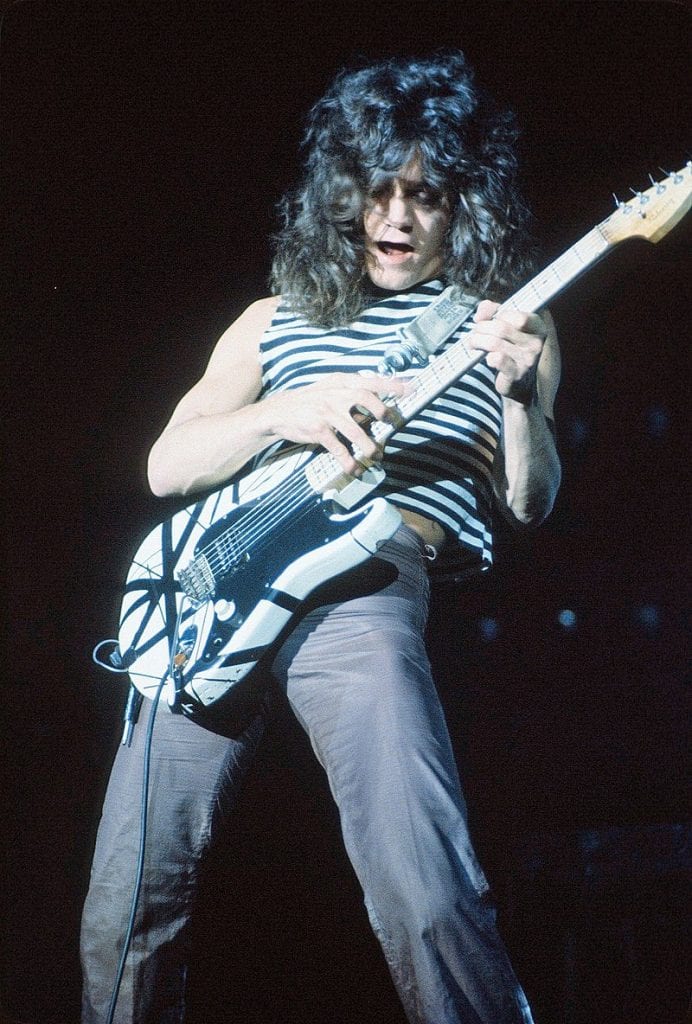

Crédit photo : Denis Cloutier

The Orchestre Métropolitain has chosen four laureates for its first Composition Competition, inspired by Beethoven’s work: Marie-Pierre Brasset, Cristina García Islas, Francis Battah, and Nicholas Ryan. Launched last March, the competition aims to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the famous German composer. Next year, the works of the winners will be premiered by the Orchestre Métropolitain under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin. This dossier series aims to introduce you to these composers and their works.

Today, we’re talking to Francis Battah, a young Montreal composer born in 1995. It was his piece entitled Prélude aux paysages urbains that allowed him to be chosen among the winners of the composition competition.

Battah studied with Alan Belkin, Ana Sokolovic and Denis Gougeon, and is currently pursuing his master’s degree at McGill with Denys Bouliane. He’s already won several prestigious honours, including the Antonin Dvorak Composition Competition in Prague, at la Société de concerts de Montréal, compositions performed by Serhiy Salov, Nicolas Ellis and l’Orchestre de l’Agora, a collaboration with actress Monique Miller, and several composition residencies (including one with l’Orchestre de la Francophonie canadienne).

PAN M 360: How did you react when you received the news of your nomination?

Francis Battah: Let’s just say it was quite exciting because it was Yannick Nézet-Séguin who called to tell me. It couldn’t have been announced in a better way!

PAN M 360: How do you see this challenge in the coming months, until May or June 2021?

FB: To be honest, the piece is already fully written! It’ll be less stressful than a commission where you start from scratch. Let’s just say that the bulk of the work is behind me.

PAN M 360: Are there still details to be worked out?

FB: Certainly, but quite minor. These are details that will be discussed directly with Yannick when he has the complete score. They mainly concern questions of tempo, correction of errors, etc. But when the orchestra has the music, we’ll only have one 40-minute rehearsal to set everything up. That’s it! We won’t have time to change things that are too precise, like rhythms or notes. And technical errors, or typographical errors, let’s say, are absolutely to be avoided. If a musician raises his hand because he stumbles on something imprecise, precious minutes are lost, and in this case, they’re at a premium!

PAN M 360: Let’s go back to the very beginning, if you like. How did you become a composer?

FB: When I received an electronic keyboard at the age of about six, the first thing I did with it was a little composition! Then I took piano lessons, but I eventually realized that I had a better chance of standing out as a composer than as a pianist.

PAN M 360: Has your career always been classical?

FB: No, I did quite a bit of jazz too. It’s music that certainly colours my musical language.

PAN M 360: Do you identify with a musical tradition?

FB: I identify myself as independent. Of course, if you want to do the genealogy of the fundamental sources that I’m drawn from, you have to talk about the “traditional” classical tradition (laughs) – that’s a redundancy, oh well – like Mozart, Beethoven and the usual suite. But there’s also jazz and a bit of prog rock, with contemporary music to fill in the rest.

PAN M 360: Speaking of contemporary music, is there a specific aesthetic to which you are more inclined to relate?

FB: Ligeti’s is very much alive in me. I recognise myself in his interest in rhythm, in his search for unusual sounds, and also in his independence. He didn’t belong to any particular “school”. For me, he’s a model.

PAN M 360: Three terms that describe the music you like to write?

FB: One, concern for harmony, whether consonant or dissonant. Two, use of forms that allow the listener to understand my message. I do not seek complexity at all costs. Rather, I try to communicate ideas that can be very complex and refined as directly and simply as possible. Three, diversity. I like to touch on all sorts of things, to express characters that are very different from one another depending on the work.

PAN M 360: For you, what is more important: sound or harmony?

FB: I think of the notes and their harmonic organisation before the raw sound. That’s my starting point. That said, afterwards I always work on the sound finality of the work. And here I come back to Ligeti: he had the ability to navigate between the two, between harmony and the raw, virgin sound. I like this type of in-between, this search for links between two opposing premises.

PAN M 360: What do you prefer, music that expresses musical ideas or music that expresses emotions?

FB: I tend towards emotions, but there’s a need for nuance. I don’t try to bring them to the forefront. Once the inevitably abstract process of musical composition is completed, I think one must feel something, despite the complexity of the construction.

PAN M 360: In your opinion, is there a difference between today’s academically trained composers and those of the past?

FB: Yes, previous composers did not have such broad and easy access to everything that was being done around them. Today, we’re awash in countless influences, coming from all over the world, and almost in real time. It is sometimes even difficult to channel all the ambient noise. For some, the solution is to make a cocoon that only includes the traditional lineage, from classical music (Renaissance, Baroque, etc.) to pure contemporary music.

PAN M 360: How do you position yourself in the face of this?

FB: I didn’t grow up with classical music. I love it, but I can’t deny that I learned to love and appreciate something else as well. I have friends who do jazz, electro, pop, it inspires me indirectly.

PAN M 360: How do you see the movement of “accessible” contemporary music, so-called neo-classical, such as that of Ludovico Einaudi, to name a very obvious one?

FB: I don’t feel at war with it. On the contrary. We have to ask ourselves, wwhat makes this music sound contemporary? Because despite its very simple and consonant harmonies, it couldn’t have been written like that 100 years ago. There is clearly a way that’s contemporary, the construction of the chords, their relationship to rhythm, the arpeggios, etc., and the way it is written. In one piece, I wanted to take these ultra-simple, almost primitive ideas and develop them further. So I was inspired by them.

PAN M 360: Which work have you been most proud of?

FB: A series of six preludes, written with the pianist Philippe Prud’homme. I am very proud of that.

PAN M 360: Is there an overall, long-term project that drives you as a composer, a legacy you would like to leave?

FB: I’d like to found my own ensemble, bringing together musicians from various horizons such as improvisation, jazz, classical and invented instruments. I’d like to mix it all together, add synthesizers, electro, and try to make a 21st-century symphony. Because it’s not going to be possible to do it with the traditional symphony orchestra. You have to add a lot of instruments to represent today’s creativity. And it takes more than 40 minutes of rehearsal to be creative like that!

PAN M 360: Describe Prélude aux paysages urbains, the work that will be performed by the Orchestre Métropolitain.

FB: I was inspired by the 6th symphony, the Pastoral. My idea was to do the same thing but for an urban landscape. What character does the modern city represent? I use the main theme of the first movement, I hit it, I fragment it, I give it another rhythm, sometimes breathless.

PAN M 360: I can’t wait to hear that in May or June 2021! Thank you for this beautiful meeting, and good luck!

FB: Thank you!