One evening in the summer of 2015 at the Symphony House, Wayne Shorter was performing with this excellent quartet that had extended its creative life on stage, against all odds. That night, however, it felt like the beginning of the end. It was obvious that the master no longer had the absolute mastery of his instruments (tenor and soprano) that he was known for even at his eighties, and that his improvisational dialogue was no longer as alert and solid as it had been throughout his life, since his early days with drummer Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

One could tell that the smiles of his accomplices hid a certain sadness, and I told myself that this was my last Wayne Shorter concert. Seeing him on stage again in such a diminished state? Nay. This immense composer, improviser and performer would never again be what he had been: for more than 60 years, one of the most brilliant of this music that we still call jazz.

Eight years after this sad report of his loss of faculties, a few months before reaching the age of 90, Wayne Shorter passed away. Even today, the general public and even the general public of jazz will not put him in the pantheon of the unavoidable. A discreet character, not very talkative, but nevertheless interesting in what he had to say (having spoken to him many times, I can testify to that), he expressed himself first of all by his achievements.

His creative qualities and intellectual curiosity led him to change jazz after its golden age of hardbop, by injecting more modern music from the Western classical tradition and more non-Western modal music into the lineage from which he came. Up until the 1950s, jazz had certainly integrated post-romantic and modern classical music, especially impressionist (from the French composers as Ravel or Debussy). It was heard with attention, from Duke Ellington to Bill Evans through Miles Davis’ first quintet, especially in his collaborations with the arranger Gil Evans. Wayne Shorter, on the other hand, showed an even deeper knowledge of modern and contemporary advances in classical music and used them brilliantly without these colors prevailing in his essentially jazz work.

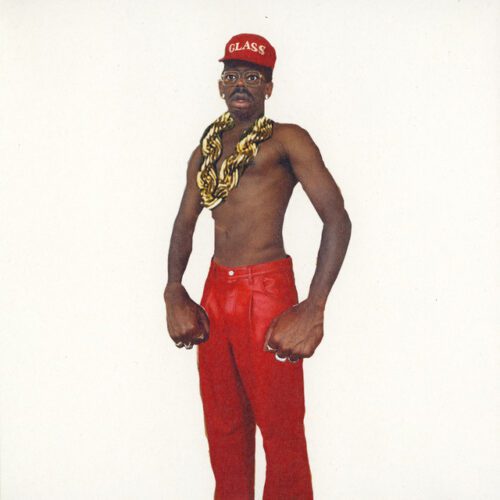

Why is Wayne Shorter less quoted than the great icons of the style? Most probably because he didn’t have the media flamboyance and swag of Miles Davis, for whom he was the crucial composer in the famous quintet of the 60’s – Herbie Hancock, piano, Tony Williams, drums, Ron Carter, double bass, Miles, trumpet, Wayne, saxes. Without him, this historic quintet would not have been able to count on the compositions of such an acoustic apotheosis: “Nefertiti”, “Footprints”, “E.S.P”, “Fall”, “Pinocchio”, “Iris”, “Orbits”, “Dolores”, “Prince of Darkness”, “Limbo”, “Vonetta”, “Parephernalia”.

Under the Blue Note label, the saxophonist had a parallel career, his solo albums are in the same spirit as the Miles Davis Quintet, but with less impact for the reasons we have just stated. It is therefore necessary to listen again to these essential recordings of the jazz of the 60’s, especially “JuJu”, “Speak No Evil”, “Adam’s Apple”, “Super Nova”. As he did with Miles, Wayne Shorter was tracing the post-hardbop path while remaining faithful to melodic themes and consonant harmonies, while Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, John Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, Albert Ayler and so many others were admitting atonality and arrhythmia in their proposals.

At the end of the 60s, the famous jazz electrification sessions led by Miles Davis constituted the founding community of jazz-rock, later renamed jazz-fusion, for better or for worse. His complicity with the Austrian keyboardist and composer Jozef Zawinul, central architect for the mythical Miles Davis album, In “A Silent Way”, a founding recording if ever there was one.

The founding of Weather Report with Joe Zawinul was the most interesting extension of Miles’ early electric work (“In A Silent Way”, “Bitches Brew”, “Jack Johnson”, “On The Corner”, “Big Fun”). The first recordings, “Weather Report” (homonym) and “Sweetnighter”, were very close to this sound, the identity of the band had then become clearer with I “Sing the Body Electric”, “Mysterious Traveler”, “Tale Spinnin’, albums whose rating will not cease to rise with time if you want my opinion In 1976, we witnessed another turning point with the opus “Black Market” and the arrival of Jaco Pastorius within WR. This spectacular entry of the superbassist coincided with a sound closer to African and Afro-Caribbean music, put forward by Zawinul and endorsed by the band. Advance or watering down? Advance at the beginning, watering down afterwards…

Some deplored Shorter’s overly effete posture as a soloist and conceptual leader, a posture he maintained until the end of the group. Things had progressively gone wrong with albums that were really too sweet, after the release of the opus “Heavy Weather” in 1977, certainly the most famous of the WR discography. Afterwards, we witnessed the decline, until 1985 with the release of the cheezy “Sportin’Life”.

There followed a renaissance of Wayne Shorter as a leader and composer, while Zawinul continued WR’s work by hiring several non-Western virtuosos – Ivorian drummer Paco Sery, Mauritian bassist Linley Marthe, Cameroonian bassist Richard Bona, etc.

From the mid-70’s until his death, Wayne Shorter’s genius was progressively recognized by jazz lovers of all tendencies, from left field to right field.

This recognition came first with the memorable Native Dancer released in 1974, an album featuring the Brazilian singer Milton Nascimento, and whose concert in Montreal much later, in the late 80’s, was one of his most dazzling. The albums “Atlantis” (1985), “Phantom Navigator” (1986), “Joy Rider” (1988), and “High Life” (1994) were shorter extensions of an aesthetic that had been influenced by Weather Report, but without Zawinul’s Afro-pop impulse – which had reached its limits.

At the turn of the millennium, it was safe to assume that everything had been said by each entity of the famous tandem that created Weather Report.

But Wayne Shorter was about to surprise us with a new acoustic quartet, based essentially on real-time improvisation: Danilo Perez, piano, Brian Blade, drums, John Patittuci, double bass. The contribution of this quartet far exceeded expectations, memorable concerts followed until the announced decline in 2015. Here and now, the leader integrated the many themes and harmonic progressions of his compositions in his cranium. We remember the albums “Footprints Live!” (2001), “Alegria” (2003), “Beyond the Sound Barrier” (2004), “Without A Net” (2010). And we don’t count Shorter’s work in chamber music, an angle that we would have liked to have been more nourished given the convincing results.

The creative life of Wayne Shorter, a follower of Nichiren Buddhism, was marked by a few tragedies: the short life of a severely handicapped child and the untimely death of his second wife Ana Maria in a plane crash. In this respect, the musician was true to himself, very discreet publicly about what, after all, is none of our business. On Wayne’s side, what is our business… can be heard.