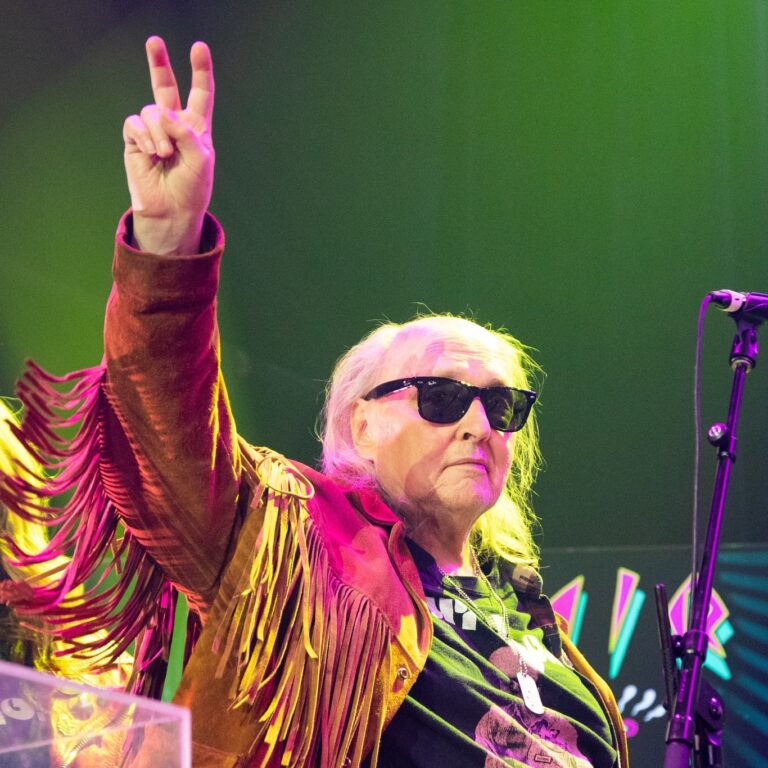

Photo Camille Gladu-Drouin

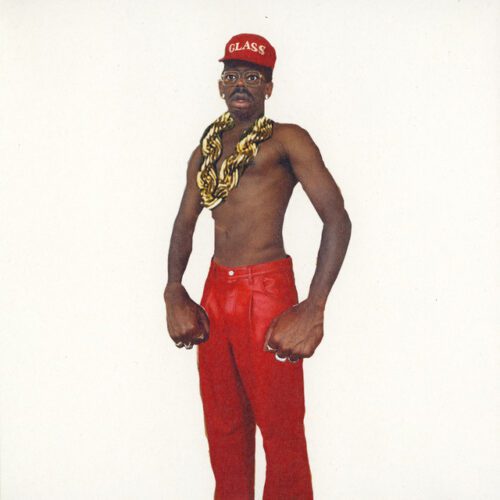

September 9, 1948 – November 6, 2024

It was the day after the incarnation of Le Cauchemar américain that Lucien Francoeur strapped his last piece of luggage onto his bicycle and took off to join the big band on the other side. As befits his legend, the media paid tribute to him, and I think he would have been quite pleased with the effect of his release. In any case, I’m very proud for him, finally back to being as big as he should have been.

Too young to have known Lucien Francoeur during the first Aut’chose period, it was with the classic Nancy Beaudoin and Rap-à-Billy (and the Burger King ads) that I became aware of his existence. It was also the CKOI era, with its garage plogues, restaurants and elevator returns. I heard he also read poetry there, but I never listened to him long enough to witness it, he made me want to change the station. In my mind, he was associated with Gerry Boulet-style Quebec rock fm, nothing to make me want to listen to the vinyl that was lying around in my mother’s record stack.

In 2001, I was working at Foufounes Électriques when Aut’chose attempted a comeback with La Jungle des villes, an album of little interest, and given the scattered crowd present that evening, it was a comeback that didn’t excite many people. I watched 3-4 songs to see what Aut’chose was all about, but it still wasn’t the best introduction and I ended up spending the rest of the show at my desk waiting for it to finish. On my way round afterwards, I bumped into Lucien in the dressing room, but given my preconceptions, I looked down on him a little and he gave it right back, ha ha.

It was in 2005, with the 30th anniversary show of his first album and the release of Chansons d’épouvantes a month later, that things clicked. Attracted by the supergroup revisiting Aut’Chose classics, with original member Jacques Racine (who died on September 18) joined by Denis “Piggy” D’Amour and Michel “Away” Langevin of Voivod, Vincent Peake of Groovy Aardvark and Joe Evil of Grim Skunk, Aut’chose’s music suddenly took on a dimension beyond the caricature that had come to replace the original. Lucien shone outright, proud to present this version of Aut’chose, proud to still be there and proud to be where he belonged, at the front of the stage with a microphone in his hands.

And he was out of his “tank salesman” phase. Finally. And he understood how lucky he was to have these musicians with him, he was still Francoeur but with a less pretentious tick. And it also helped that he was with musicians I considered to be part of my gang.

So I gave Aut’chose another chance, starting from the beginning and bang, everything fell into place. I understand the shock of the time and the influence it had on the rest of Quebec rock, musically in tune with the trippy rock of those years and, above all, with a unique frontman who gave Aut’chose’s discography all its flavor.

Inhabited by an almost naïve ideal of rock’n’roll and its importance, Francoeur’s persona was as shocking, if not more so, in interviews than on record or on stage, which helped to boost his personality to the eventual detriment of the band. But the seed was sown, and for better or worse, the Francoeur effect has been felt ever since.

It was when the book L’Évolution du heavy métal québécois was published in 2014 that I really met Lucien for the first time. As my view of him had changed and when he felt he was loved, Francoeur made way for Lucien, it clicked.

A few months later, I decided to change the name of the trophy awarded to the Gamiqs from Panache to Lucien. Because he deserved to be recognized for his contribution to the history of rock in Quebec, particularly for his influence on what was to become the alternative scene, with Voivod of course, but also Groovy Aardvark, Grim Skunk, Gatineau, Galaxie and many others, but above all for his attitude which, in my opinion, was as fundamental to the building of his legend as his poetry or the music that carried it. Because that’s what made the difference. And still does, it’s what explains the success, or otherwise, of one artist over another. In short, I thought it epitomized the idea behind GAMIQ.

He wasn’t the first, but he was the one we were talking about. Because he was unique, the timing was right and he seized the opportunity. It’s a chemistry that’s hard to achieve, and even he often failed to find that state of grace, but by the early 70s, Francoeur was on his x and building a monument that still stands today.

Because beyond his discography or literature, it’s his influence that will be remembered in Quebec history. It’s not about chart-toppers or trophies on the mantelpiece, but about a work that marked its era and inspired the rest of history. Not many artists can boast that. Lucien Francoeur can.