Over the years, the music of Pierre Boulez has become the yardstick by which contemporary music is judged. A model of intellectual rigour for some, a symbolic scarecrow of cold, dull brainyism for others. However you look at it, you cannot underestimate the scope and fundamental importance it has had and continues to have on the musical world as a whole.

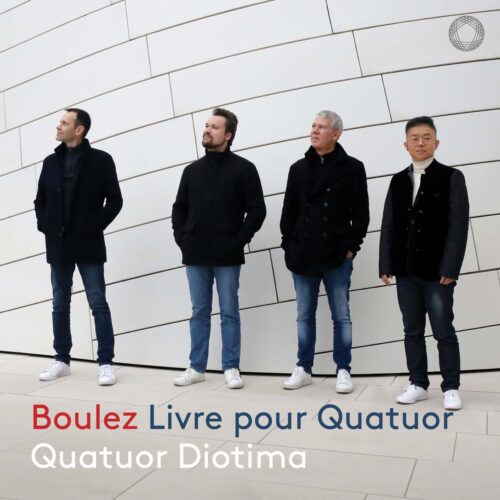

Boulez almost made the ‘work in progress’ a personal trademark. Several of his major compositions were developed over years, even decades. Such is the case with the Livre pour quatuor, his one and only string quartet, which he was careful to name so as to mark the dissidence he intended to embody in relation to the structural tradition in art music. Boulez began composing it in 1948, and was still working on it when he died in 2016. Only five of the six movements originally planned had come to life, and have even been recorded. Curiously, but understandably in Boulez’s case, it was the 4th and not the 6th movement that was missing.

Unfinished, then, but sufficiently advanced and sketched out for the composer Philippe Manoury to succeed in completing it and allowing, some 70 years after Boulez’s death, its true birth as a definitive work.

It was with Livre pour quatuor that Boulez made his paradigm shift as a composer. He had just finished the first two piano sonatas, which are somewhat a culmination of his first compositional period, the one still attached to a certain classical structure, when he launched into a new creative life, centred on the rejection of the century-old principles of art music. Livre pour quatuor is a brilliant and fundamental essay in rigorous serialism, both harmonically and rhythmically. It is one of the most important early examples of the ‘sound’ of typical contemporary music, which many have come to revere and many others to hate. What I also call ‘pointraitisme’ (dashdotism?), because music is, from the perspective of two-dimensional sound illustration, made up of dots and dashes, some notes extremely brief and others sustained for longer (but never to become a line. Just a dash).

The changes of timbre are abrupt and incessant, the techniques used extensive (sul ponticello, col legno, pizzicato of course) and the contrasts of character, subtle but assertive, follow one another from a dry austerity to an almost improvisatory suppleness (which may come as a surprise when you know Boulez and his maniacal obsession with controlling the narrative).

The music is utterly bare, and its interpretation is a remarkable intellectual, interpretative and artistic achievement. Textures are ceaselessly stretched, disintegrated, sketched out, only to attempt a new incarnation. We witness a ballet of quantum particles that come to life in an apparently random fashion, when in reality the construction is nanometrically calibrated and anticipated, but through a science that is impossible for us ordinary mortals to grasp. All that’s left is to plunge in, clinging to our initial sense of curiosity about what lies on the other side.

The Quatuor Diotima already recorded the five-part version several years ago, but this ultimate creation, remarkably performed, now becomes the ultimate in Boulezism, and the gesture that definitively closes the debate around this work, one of Boulez’s most personal (it accompanied him all his life!), and also one of the most significant for 20th-century music.