There is something almost scripted about the appearance of this Requiem by François Dompierre. One of the best-known and most emblematic composers of modern Quebec, long associated with film and popular music, genres long seen as ‘minor’, he is becoming increasingly respected by the ‘serious’ establishment and composing many works in traditional classical architecture. In his later years, these included the 24 Preludes, the Cello Concerto, a Concerto grosso and a Fantasy for piano and orchestra. At the age of 81, at the peak of his art and a rich career, he plunges into one of the most symbolically powerful exercises in Western music since Mozart: a Requiem.

Choir, orchestra and soloist (a tenor and a soprano), the form could not be more classical (in the sense of learned music). The treatment is in the image of Dompierre: a skilful and elegant blend of classical, romantic and popular modern influences (but not too much in this case).

The choral part is important, leaving less room for the vocal soloist. The approach is not surprising: there is something decidedly more cinematic or visual about large ensembles. And Dompierre excels magnificently in this ultra-communicative way. One might have feared pastiche. But nay! Yes, the harmonic language is firmly rooted in Romantic tonality, with many reminiscences of Fauré’s and Duruflé’s own Requiems, but it is also used with an economy of modulation that brings us back to modernity, with hints of quality film music and echoes of the Welsh Karl Jenkins (incidentally, who is almost the same age as Dompierre : 80) and the Englishman John Rutter. In any case, Fauré and Duruflé are among the most frequently used sources of choral inspiration in film music. In short, the melodies are beautiful and accessible, but not superficial and cheap.

Dompierre knows how to capture the audience’s attention. Take, for example, the Dies Irae, which begins with whispers (Dies irae, dies irae…) before being enhanced in counterpoint by the original Gregorian chant. What a beautiful effect! The central movement of the Recordare is particularly powerful. A Faurean melody in the tenor blossoms over a tender orchestra, then is supported emotionally by the choir, before the movement concludes in a grand apotheosis. Applause guaranteed.

I could go on describing each movement, the febrile and solar Sanctus, the melancholic Benedictus, the strangely dreamlike but above all deeply soothing Agnus dei, the stentorian initial Kyrie, the celestial and organic final In paradisum with its percussion exergue, and so on. But that would be tedious and boring. Instead, I invite you to dive in and listen to a work that is sure to leave a lasting impression, worthy of an artist of profound sincerity, gifted with a unique ability to create musical frameworks that you love to immerse yourself in without resistance. Go on, dive in.

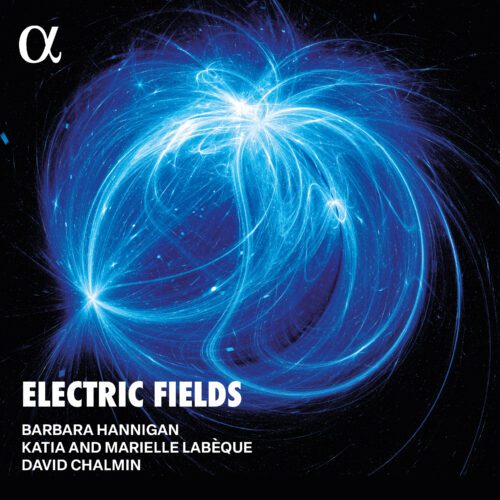

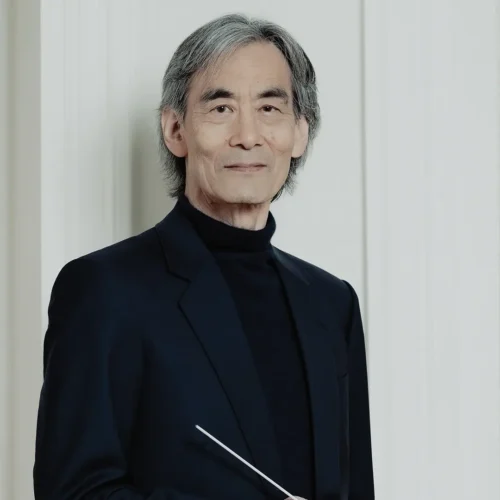

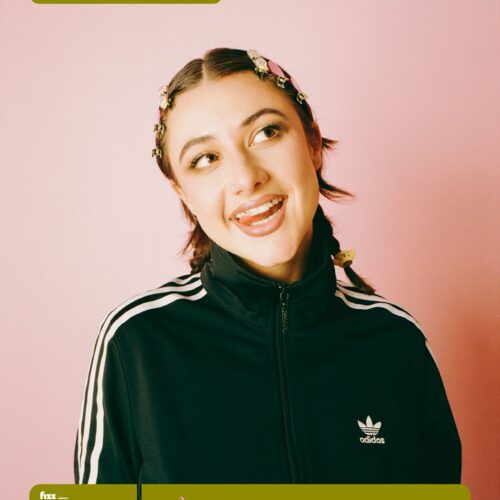

Hats off to the artists present, all of them good: soloists Myriam Leblanc, soprano, Andrew Haji, tenor and Geoffroy Salvas, baritone, the Ensemble Art Choral and the Orchestre FILMharmonique, conducted by Francis Choinière, who are used to deploying a wide palette of sumptuous colours thanks to the many film-concerts in which they play music by John Williams, Howard Shore and many other great Hollywood composers.