Additional Information

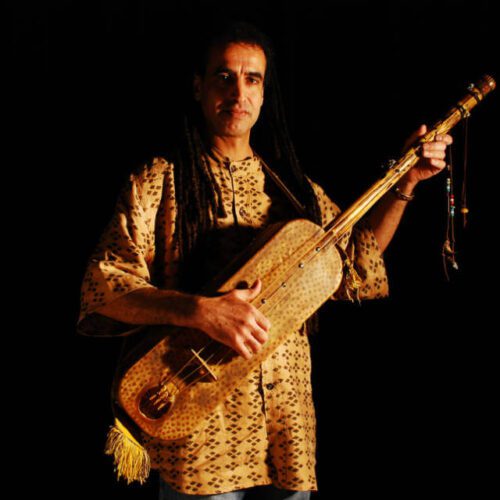

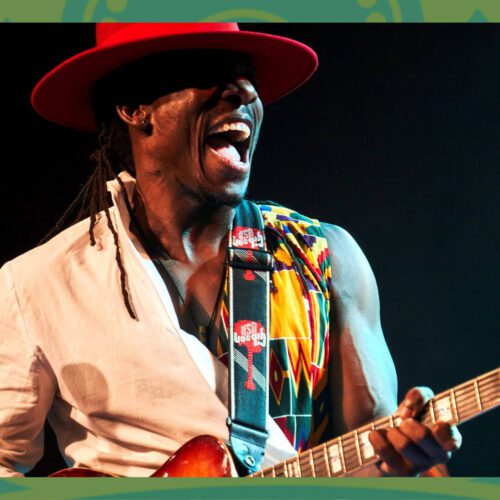

Photo credit: Sarah Bo

The foundation of Pantayo’s sound is kulintang, which is, as band member Kat Estacio explains, “a group-based form of atonal metal percussion and drum music that originated in Southeast Asia, and the specific tradition that we borrow from and are inspired by is from the Maguindanao and T’boli tribes from the southern part of what is now known as the Philippines.”

The one reference point most new listeners might have for kulintang is Indonesian gamelan, a similar metallophonic music, its rich clangour familiar to anyone who’s seen the famous anime film Akira. There are pronounced distinctions, however.

“Kulintang is a community ensemble, meant to bring people together – in ceremonies, weddings, and so on – and is used for relaxation after a long work day,” says Estacio. “From what I know, gamelan is more like an orchestra, played in courts for the enjoyment of royalty. With this in mind, it makes sense to me that kulintang instruments are tuned to each other, and the tunings depend on the maker. There is no one way to play kulintang – innovation, interpretation, and playing according to how you feel is encouraged. It also makes sense that anybody, regardless of class or social role, can just pick up and learn kulintang.

“1960s psychedelic music popularized the gamelan,” adds Jo Delos Reyes. “It was through the Western lens of the exoticization of the ‘orient’ that the gamelan became more highly researched. Gamelan has more standardized tuning, whereas kulintang does not follow specific tuning. The tuning depends on the making.

“This resulted in a really interesting and sometimes challenging songwriting experience for us, as we tried to write with tuned instruments. It made us reimagine new ways of approaching how we use kulintang-ensemble instruments in our arrangements.”

Kulintang, it’s vital to note, is originally women’s music. “This was a tidbit that we didn’t know initially,” says Estacio.“We learned about it as part of our ongoing decolonization work, to inform ourselves of the context that kulintang music comes from.

“What I learned from one kulintang teacher, Titania Buchholdt, is that since the Maguindanao culture is a mix of indigenous and Muslim cultures, some if not most of them follow a rule where a woman isn’t able to travel without being accompanied by a man from her family – husband, brother, father, uncle, son. This resulted in Maguindanao Kulintang teachers in North America, and in some cases in Manila, to be mostly men.”

“However, we also remember women, queer, and two-spirit people’s important roles in a lot of Indigenous cultures. They are birth workers, mothers, healers, priestesses, musicians, performers, and occupy a variety of other roles that are central to their respective communities. It is no surprise to me to now make the connection that women are at the centre of kulintang music traditions too.”

“Pantayo has nurtured us in many tender and constructive ways that enabled our personal growth,” adds Michelle Cruz. “Being an all-women band certainly contributes to that.”

“As women,” Estacio continues, “I also think that playing a percussion instrument is so empowering and an important addition to the narrative of what women’s roles are, in labour and in music. At the end of the day, playing gongs, just like any percussion instrument, is very cathartic!”

Assembled bit by bit over the course of several years, Pantayo (on the label Telephone Explosion) acts as a record of its own creation, an “audio diary”, as the band puts it, of their collective evolution. Essential to that process was producer Alaska B, leader of Yamantaka // Sonic Titan. She’d worked with Pantayo since 2014 on various projects, including the score for the award-winning video-game Severed in 2016, and YT//ST’s 2018 album Dirt. Pantayo’s Delos Reyes also sings in YT//ST.

“Prior to this album project,” recalls Kat Estacio, “we were only playing live shows and offering our KuliVersity music and cultural workshops on how we learned, and play, kulintang. Alaska offered a perspective that having an album works like an archive, so that there’s a record of kulintang music played by queer diasporic women in Toronto in 2020.”

“It ended up being outside the scale of most projects I’ve worked on,” Alaska B recalls, “as it was spread over many years of on-and-off work. At the beginning, they had envisioned it as taking the gongs to outer space. I remember Michelle sending me a message using alien and ghost emojis to describe her ideas, so we tried to work some very electronic ideas into their very not-electronic gongs.

“I tried to keep the focus on the dynamism of live performance by wrapping their performances in electronic layers, instead of trying to build a base layer and inserting the gongs on top, so many of the gong elements were recorded first, and then built on top of, months after.”

“As it was the band’s first shot at making a record, we honestly did not have a clear direction, and Alaska helped us navigate this,” says Cruz. “She encouraged us to really dig and find our way. She warned us that it would be a tough grind. She didn’t sugar-coat anything.”

“Alaska ingrained in us a type of work ethic,” says Estacio, “to get to know our instruments so well that we could fall in love with them over and over again. I think this is one of the reasons why each song in the album sounds so different. This collection of songs is a way for us to present the different explorations we’ve allowed ourselves to go through during this process.”

“When we first started working on the album in February, 2016,” says Eirene Cloma, “Alaska asked us a question somewhere along the lines of, ‘who is Pantayo without the gongs?’ This forced us to think about our individual and collective creative expressions outside of kulintang music. Our first foray in this different way of thinking was when we wrote ‘Eclipse’.”

Appropriately, ‘Eclipse’ opens the album. It’s followed by lead single “Divine”, possibly the most accessible tune for new listeners. “To me, this song speaks about how love is action, labour, and a sacrifice,” says Kat Estacio, “whether it’s romantic, platonic, to your pets or plants or whatever. And most of the time, the universe conjures alignments beyond our control – and this is how we meet people whom we have deep connections with. The universality of it seemed like the perfect introduction to Pantayo.”

Also appealing is “Taranta”, alternately vulnerable and combative, with its taunting chorus – see the TV appearance, above. “The verse and bridge melody was inspired by ’90s R&B and hip hop,” says Cruz. “The lyrics were heavily inspired by assholes.”

The title, Estacio explains, “means to panic or to feel frantic, as a mindless response. The chorus came together as a way to rally up the ego, a means to tell myself to keep my composure and not let myself be affected by what other people think, and to tell those who don’t got your back – or worse, those that put you down – to fuck off, ha ha!”

Then comes “Heto Na”, all gentle and elegant before switching up into some bouncy hip hop fun. “It takes inspiration from ’70s disco OPM (Original Pilipino Music), vogue and ballroom beats from queer dance parties that we go to, and drum-and-lyre ensembles at town fiestas in the Philippines,” Estacio says of this one.

“The lyrics came together super last minute. If I remember correctly, it was written the night before we were going to track vocals in the studio. The song asks its listeners to loosen up and dance, to take ownership of not only their bodies but also of the dancefloor.”

“When we brought on Tricia Hagoriles as director,” says Katrina Estacio (Kat’s sister) of the video for the song, “we knew we wanted to portray the environment we had in mind when we wrote it: a world of our own where we can let loose, connect with our friends, and just be. Our members Eirene and Kat individually contributed music to Tricia’s previous films The Morning After and Lola’s Wake, respectively. We adore her work so much.

“Tricia’s world-making is very much connected to her style, which made her a really good fit for this project. The ‘Pantayo world’ she created in the video feels lush, warm, and fun! Complemented by the motion graphics of Manila-based animator Pauline Vicencio-Despi, production design from Toronto-based artist Cathleen Calica, and the Tita Collective, we were able to capture a piece of the dancefloor of our dreams.”

Of “Kaingin”, Kat Estacio says, “the vibe of the song is pretty heavy and sorta silly. The synths are so anthemic, but in like a hilarious ’80s prog-rock, anime opening-sequence sense. The title means ‘slash and burn’, as in, the agricultural process. It’s a tribute to the land that we are so grateful to reside and create on – Tkaronto, the land of the Haudenosaunee, the Petun, the Wendat, the Anishnaabe, and the Mississaugas of the Credit, and a tribute to the Indigenous peoples that our instruments and kulintang knowledge is inspired by, the Maguindanao and the T’boli.

“The lyrics talk about oppressive systems – colonial, patriarchal, heteronormative, ableist, racist, classist, fascist, etcetera – and the exploitation, marginalization, and trauma of Indigenous peoples. These aren’t easy topics to talk about, so I thought Alaska’s approach of making the vibe a little light was an accessible one, to bring this message forward.”

The album’s fifth track, “V V V (They Lie)” is the one with the lowest kulintang quotient. It’s also the most uplifting, to this writer’s ear.

“‘It’s uplifting for me too,” says Estacio. “We wanted this song to feel free. This song feels like the closure that you give to yourself, because it sure won’t come from any other person. A quick side note – in numerology, 5 is a pivotal point, the middle of 1 through 9. It symbolizes positive change and can bring hopeful opportunities in the future.”

“We formulated the song over bubble tea,” adds Katrina Estacio. “The only prominent ensemble part is the bandir, the timekeeper. It started as a scratch recording when we were thinking of what our sound would be like if we removed kulintang, after Alaska posed us the question. It helped us describe our sound to be lo-fi R&B gong punk.”

“Although the process had its share of challenges,” Cruz reflects, “it was a process we had to go through in order to grow – and finish an album!”

The stretched-out timeframe was among those challenges, for all involved. “The most difficult part was keeping on top of a project that lasts that long,” says Alaska B. “Lives change a lot during that period, and it was constantly broken up by my touring, so it was like rediscovering the project constantly until there was nothing left to rediscover, and it was just time to call it done, export, finished.

“The one great thing about it was how close we all became. We had been collaborating on Severed already, but instead of this being a project that took a month or so then never talk to each other again, it was something that kept us connected while everything else around us was changing.

“I’ve consumed hundreds of momos and gallons of coffee with them, working in the studio, they all attended my wedding, and Jo and I ended up logging at least 150 days on the road together with YT//ST. There’s a lot of love in that record.”

“I guess it’s fair to say a lot of our earlier recording, particularly on SoundCloud, was part of our process of how we got to where we are today,” says Delos Reyes. “We worked hard to get to where we are, but really didn’t plan it out this way. Working with Pantayo and our collaborators is like a creative safe space where we feel comfortable collaborating, learning, and making mistakes with each other in exploring all the sounds!

“I think it’s important to note that kulintang music is traditional in a sense that is the OG Filipino music (!!), and not in a sense that it is fixed and something of the past. This is still practiced and evolving every day. With the migration of Filipinos across the globe, it’s great to see the ways in which kulintang music is being explored in different Filipino-diasporic communities, and how our different environments, both sonically and geographically, can create a sound.”