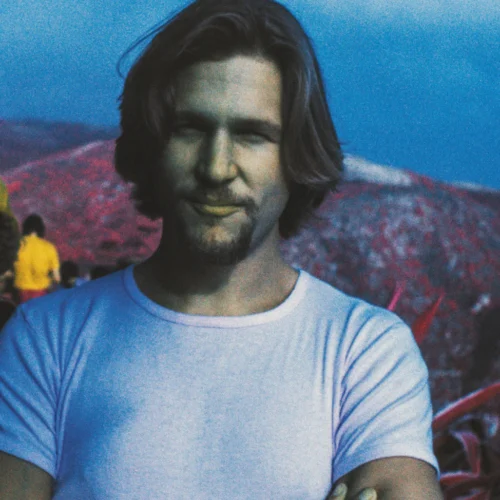

The Orchestre symphonique de Montréal opened its 91st season this week with Arnold Schoenberg’s rare and impressive Gurrelieder, to mark the 150th anniversary of his death.

This is a rare and impressive work, due to the sheer number of performers required: a very large orchestra (on Friday, for example, there were 7 trombones and 14 double basses), 6 soloists and a huge choir; in other words, between 300 and 350 performers for a duration of around 1 hour 45 minutes.

The Gurrelieder (pronounced Gourrelider) is one of Schoenberg’s last compositions before his breakthrough three years later, and the reason for his worldwide fame. By way of background, in 1913 with Pierrot Lunaire, he broke away from the system on which all composers had written since Bach, to treat sounds separately rather than according to the notion of scale, or tonality. To situate the reader, the Gurrelieder are halfway between Richard Wagner’s aesthetic for melodies and themes and that of Richard Strauss for orchestration. The poems are written by Danish poet Jans Peter Jacobsen, and tell the story of King Waldemar, who falls in love with Tove. His jealous bride, Dove Waldemar, causes Tove’s death. Furious, the king rages against God, whom he blames for making the event happen. The king then raises an army of the dead who, for one night, sow terror and destruction.

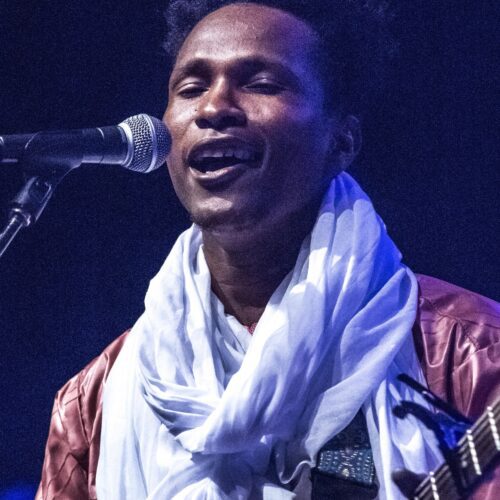

The first thing you notice is Rafael Payare’s incredible accompaniment skills. Constantly attentive, he manages to ensure that the huge orchestra follows the melodic line sung by the soloists with great precision. With such a large orchestra, it’s only natural that the soloists should be buried here and there, but it’s during the purely instrumental moments that we see just how restrained and attentive the musicians were. Seeing this, we’re already looking forward to the concert versions of Mozart’s operas he’ll be conducting later this season.

Speaking of soloists, two stand out; Clay Hilley (tenor, Waldemar) and Karen Cargill (alto, Dove). The former excels with clear melodic lines and convincing stage presence, and the latter is downright terrifying in announcing Tove’s death at the end of the first part. Slowly but surely, her single intervention led brilliantly into a tragic B-flat minor chord in the trombones. Her deep voice was so touching that we couldn’t even measure the length of this lied, so carried away were we. Honorable mention to Ben Heppner (narrator); by far the most audible above the orchestra.

After more than an hour of music, the choir entered the stage, and despite the distance between us, we were surprised by the men’s first, powerful “Holà”. In crisp German and surgical accuracy, they offered us another sublime moment when accompanied by a few musicians (woodwinds and trombones). Symbolizing the army of the dead, the men’s chorus with low brass brought us a rare, long moment of calm. This kind of open passage is dangerous when the sound mass has been dense for a long time; it was mastered.

This concert would have been excellent without it, but we thought it would be interesting to add a lighting effect, the cherry on top of the sundae. This addition immersed the audience in the spirit of the story, helping them to follow its course. Depending on character and emotion, the background lighting changed subtly or drastically, without ever suddenly catching our eye. A perfectly justified exception was the end of the work, where at sunrise, the entire auditorium was illuminated in a majestic apotheosis.

Photo: Antoine Saito