The third of four programs in the OM Beethoven Marathon took place at 11 a.m. Sunday morning, with the presentation of the Eighth, Fourth and Fifth symphonies. Given Beethoven’s reputation for selling out, it was surprising to find that the Maison symphonique’s parterre was sparse and the boxes downright empty, despite the presence of the Fifth on the program.

The first movement of the Eighth is uneven from the outset. Articulations are not homogeneous in the different sections of the orchestra. In the strings, the staccatos are very short, but in the winds, they are more elongated, especially the resonance of the timpani. Phrasing quickly falls flat, and the forte soon reaches a plateau. The second movement is much better.

Very humorous, the incessantly repeated notes lead the rest in lightness. Punctuated by sforzandos, the effect of surprise is successful. The third movement, Tempo di menuetto, has only the tempo of a minuet, as there is no room for dancing. The third beats don’t go far enough towards the following first beats, and the latter are pressed too hard. The rest of the piece is fairly similar, i.e. faultless but lacking in sparkle.

In the Fourth, surprise! We’re treated to just the opposite.

The sound balance between sections is well adjusted, especially in the slow introduction to the first movement. This mysterious, soaring introduction leads us step by step to the festive, energetic Allegro. Honorable mention to the winds and timpani for their precision. The second movement is impeccably lyrical and soothing, with phrases that breathe and settle. The scherzo that follows surprises with mischievous attacks, and the musicians play well with the syncopations that punctuate the phrases. The final movement is very light, with Yannick dancing on the podium.

After the break, it was Fifth ‘s turn to be heard. Before getting to the heart of the matter, an explanation is in order. The program states that Beethoven was the first composer to include metronomic measures in his scores, thus clarifying the rather vague speed indications, such as Adagio or Allegro , that are still used today.

Before getting to the heart of the matter, an explanation is in order. The program states that Beethoven was the first composer to include metronomic measures in his scores, thus clarifying the rather vague speed indications, such as Adagio or Allegro, that we still use today.

A surprising start, the tempo is very fast for the 1st movement. There are pros and cons to rushing it like this. By taking the metronomic speed indicated, Yannick and the orchestra express the composer’s sense of panic in the face of his own deafness and fatality.

But he doesn’t use the high points that punctuate this movement, and goes straight to where the tension can, or should, be heightened. Thus, the construction of certain phrases is rushed, as is the oboe cadenza, which is brought in abruptly. We eventually get used to this speed and this way of seeing this famous page, which nonetheless gives us momentum, even though we come out breathless.

The second movement is equally rushed and unsinging. The tempo still passes in the first two variations, but when the low strings arrive in the triple eighth notes, everything becomes blurred, so much so that the “dolce” indication becomes difficult to respect. It’s one thing to respect metronomic measures, but perhaps not to the detriment of the music, which needs to breathe.

The third movement is the most interesting, played with vigor and mystery. The call of the horns in crescendo, rather than subito forte as written, is debatable, as this is the main theme. Everything is excellent, with biting strings, except when we get to the coda, which is played on tiptoe. There’s an alternation between string pizzicatos and woodwinds on the main rhythmic motif. The woodwinds play the long notes, which is a great contrast. Nowhere else is this long motif played, so why here?

Moreover, the transition to the final movement is led by a particular instrument that we don’t hear enough of: the timpani. While the strings hold a 12-bar long note and then slowly build the melodic line, the timpani is alone in its corner, setting the rhythm and pulling the orchestra and the crescendo towards the apotheosis of the final movement, which will leave a prominent place for the piccolo, whose Fifth marks the instrument’s debut in the orchestra.

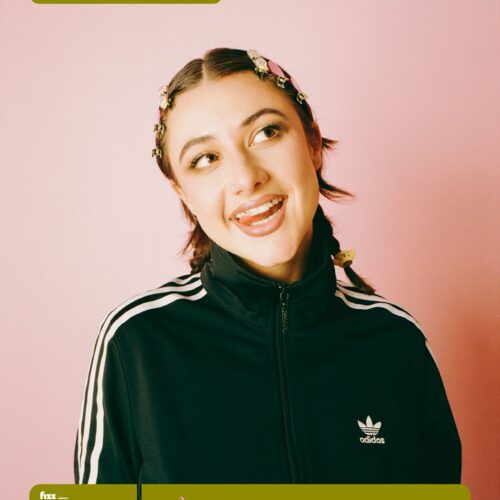

This concert is the longest on paper of the four, with 96 minutes of music. Online, it’s announced at 1:56, including the intermission, but it ends 2:15 after the start. Will OM and their leader hit the famous 30-kilometre wall that marathon runners talk about? The danger is there, as the next concert is only 1h45 away.To begin with, the premiere of Cristina García Islas’ Ré_Silience was very interesting in terms of discourse, but slightly questionable in terms of context. The work is brilliantly structured, but sounded more like a tribute to Shostakovich, so strong were the brass and abundant the percussion. Not to mention the long phrases held by the violins in the high register, doubled by the flutes, against a background of bass pedals. In fact, the basses, placed on the left, were often lost in the collective sound. To pay homage to Beethoven, in addition to quoting the second movement of the Eighth, she adds two off-set metronomes in the percussion section. Hats off to the musicians for keeping up the tempo despite those clicks!