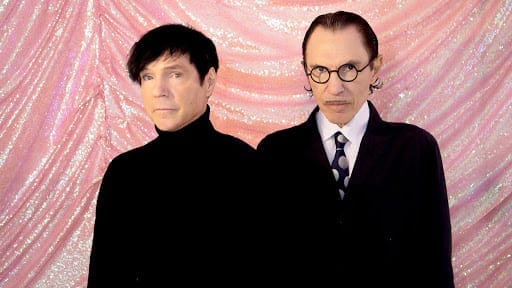

Above: Yukino Inamine and Harikuyamaku

PAN M 360: Your main intention as a musician is combining Okinawa minyo (folk songs) with dub reggae. This is a nice mix – the two music styles fit well together, even though their energies work at different levels. By the way, I think Okinawan minyo might be the happiest music in the world.

Harikuyamaku: Okinawa minyo is very unique music, different from other Japanese styles. It’s part of everyday life in Okinawa. In fact, until the reversion of Okinawa to Japan in 1972, it had been the popular music of the Okinawan people. I’ve heard that so many new minyo songs were being recorded and released on seven-inches every day, like in the ’70s Jamaican reggae scene.

Okinawa minyo is on the offbeat. That’s also like reggae music. But it doesn’t have bass. When I rediscovered my country’s music after traveling abroad, I was also becoming affected by ’70s dub music from Jamaica. I was a bass player, I like low-end sound. Then I thought to match Okinawa minyo with dub. I added bass, drums and other things, collected analogue mixers, a Roland RE-201 Space Echo and ’70s effectors like digital delays and phasers. Then, I dubbed.

The melodies of Okinawa minyo are very beautiful. As for the lyrics, there are many varieties. Classical songs to be played in the royal court have beautiful words, but many minyo have sad, suffering lyrics. There are many songs about the war in Okinawa. In addition, there are songs about changes in society and life. And also, there are many with dirty lyrics. I like that.

PAN M 360: On your first album, Shima Dub (2013), you mostly used samples from old records. More recently, you’ve started working with musicians in the studio. In fact, you have a new single with the sanshin player Yukino Inamine. Tell me more about her, and about “Ohshima Yangoo Bushi”.

Harikuyamaku: Yukino Inamine is a new-generation singer of Okinawa minyo. I think minyo singers are mostly so typical that they just sing in a faithful manner. Yukino is free and alternative. She plays live sometimes with bass, drums, and other things, and also makes new minyo songs, with words for our time. I had hoped to record with real singer for a long time. I just discovered her this year, and we’ve played live together three times. “Ohshima Yangoo Bushi” is our first recording. It’s a very old Okinawan song about Amami Island, and love. We consulted an old SP record.

PAN M 360: Your new album, Subtropica, is very different from your other work. The track “Subtropica” is almost an hour long, and it’s a soundscape, a sonic environment. It was originally a group of separate sound channels, for an installation of ceramic speakers by the Okinawa potter Paul Lorimer. I didn’t know that one can make speakers out of clay!

Harikuyamaku: Recently, I’ve become very interested in synthesizers, for making some sound effects or noises in dub. Potter Paul Lorimer’s precious presence in Okinawa, working with his original climbing kiln, gave me nice chance to express my synthesizer works. He made many different speakers, with ceramic bodies and Audio Nirvana and Fostex speaker units. Each has its own unique sound. For his exhibition, there were eight of his speakers in the space. I selected and located them, and chose what kind of sound would be suitable for each. It was super-surround!

PAN M 360: Part of Subtropica is also used for the video of Aki Bandō’s butoh performance piece, “Ninth Sense Invocation pō 2”. This is yet another context for your work, avant-garde theatre and dance.

Harikuyamaku: Butoh dancer Aki Bandō is my friend. She was looking for a soundtrack for her performance, and asked me. I like extreme expressions, so I gave her some tracks, and she liked my “Subtropica 2mix” demo. I hear she’ll present the video at some film festivals. I hope it gets some good attention.

PAN M 360: There is also a live track at the end of the album, from the show bar Love Ball in Naha City, Okinawa. It’s from a 2017 set… can you tell me more about it?

Harikuyamaku: I did improvisation live using a Korg MS2000 and ER-1, a Moog Mother32, minyo samples and effectors at Love Ball. Sometimes I do improv live, I’ve done up to seven hours before. Improv with machines is my musical challenge. Love Ball was very important club in Naha, Okinawa, that was managed by Akazuchi, the local hip hop crew. But now it’s closed. I caught a lot of good music there.

PAN M 360: So what’s next? What are you working on now?

Harikuyamaku: Right now, I’m making another song with Yukino. Recording is done. It will be released on the Chill Mountain label, managed by my friend DJ Ground. To match the label’s colour, I’m making a slow house track for the dancefloor. I’m inspired by some slow house scenes, using traditional sounds from South America. I hope to join them, using traditional Okinawan music.

I’m in some bands – Angama is a dub techno session unit with KOR-ONE, we just released our first cassette-tape album view in April. Churashima Navigator is a four-person electronic Okinawan band produced by Sinkichi – he’s also great DJ – and we’ve just released an album, and a remix album. Isatooment is techno/house production unit with Sinkichi, we released a three-track EP on Chill Mountain last year. We also use Okinawan samples. And Gintendan is five-person experimental dub band that has released two albums. I have my own DIY studio, I always work with them.