LBDA’s 1999 album, Right Back, provided for most an adequate coda to the sad fortunes of a band who lost their enigmatic frontman, Bradley Nowell, to a heroin overdose shortly before soon-to-be legions of obsessive fans outside their SoCal stomping grounds would first hear of Sublime.

But music lovers who paid enough attention to become enamoured with LBDA in their own right have long lamented the group’s retreat into relative obscurity after their 2001 studio sophomore, Wonders of the World, dropped on the unfortunate date of September 11, 2001. The band imploded shortly thereafter due to a mix of personality clashes, substance issues, and the general downpressing of those strange, early-aught end-times vibes.

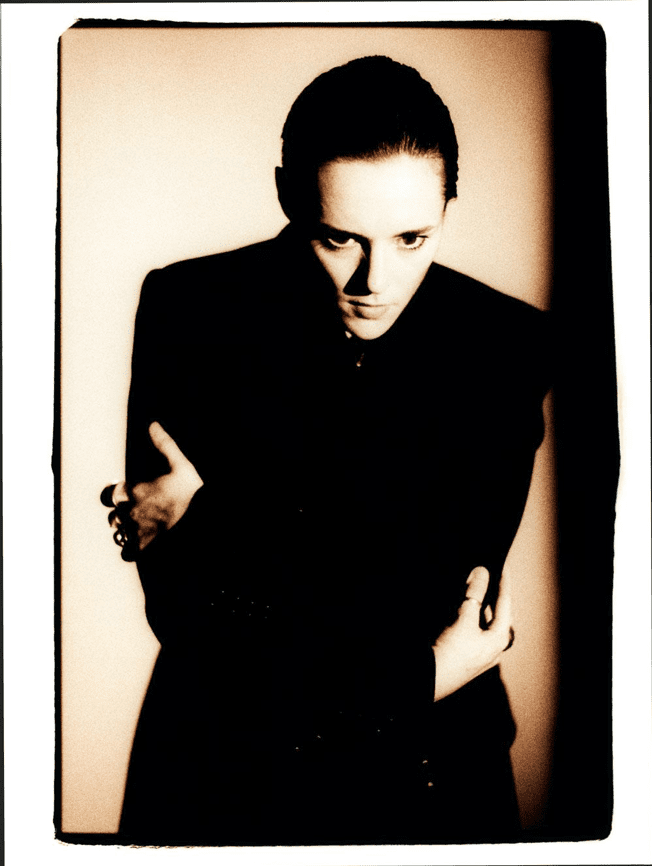

LBDA frontman Opie Ortiz – whose prior claims to fame were designing the ubiquitous Sublime sun logo as a tattoo for Nowell, and later being the toothless weirdo on the cover of Robbin’ The Hood – and his friends, ex-friends and bandmates would go on to form and disform myriad offspring projects, such as Hepcat collab group Dubcat, and Long Beach Shortbus, with the prospect of an LBDA reunion seeming increasingly less likely as decades passed.

The story between years gone by and today is too fraught to get into. The good news is simply that LBDA are back with a self-titled third outing that knocks, blending breezy roots reggae and subdued ska that doesn’t dwell in its own past. Names like Miguel Happoldt, Jack Manness, Marshall Goodman, and Tim Wu (familiar to many either from Sublime album credits or as LBDA personnel) are back, alongside vocalist/composer Ortiz.

And while dearly departed brothers Ikey and Aaron Owens may be better known for work with Jack White and Hepcat, respectively, they called LBDA family, and their deaths, as Ortiz explains, is where the story of Long Beach Dub Allstars, which dropped May 29, began.

PAN M 360: So I’ll start with a simple question and build from there. Why now, after all these years?

Opie Ortiz: I think it came as we were kinda doing baby recordings here and there. Me and Miguel would kinda work on tracks. Miguel would be consistently recording different people for different tracks. We were just kind of hammering away at little things. We wanted to actually just start putting out music, so me and Miguel and Marshall agreed to put out some songs.

We were working with Aaron and Ikey Owens. They were an integral part of Long Beach Dub Allstars and Dubcat, another recording venture that we did, and they passed very closely apart during that time, around the 25th anniversary of Skunk Records.

We had been working on tracks together and to be honest, I wanted to be sure that those tracks were used for the LBDA project, because that’s what we had all given our time to, you know?

That being said, with their passing, it was kind of like a push to finish the tracks and get them done. We had five tracks we had been working on, and there were others on the table that weren’t finished enough. We were also just kinda playing some live shows, that also pushed us. We played some festivals and that was the beginning of getting back out there.

Aaron Owens actually wrote the guitar lick [for memorial album track “Owens Brothers”] and had actually addressed it to me like, ‘Look, this one’s for you.’ I believe I sat on it for a while. And then I just started writing about them in the song and it just sort of happened.

PAN M 360: There’s a certain sense of what sounds like nostalgia on this record, combined with a greater feeling of coming into its own, compared to the earlier LBDA projects.

OO: If you listen to the song “Breakfast Toast”, that’s like, one night that happened, you know what I mean? Just taking in some of the stuff going on around, funny little things, and that’s my analogy. Some might say that time’s wasted but when you’re there in the moment, nothing is wasted. Everything’s great. So you’re toasting to really just doing nothing and partying in that moment. (laughs)

“All Gone Crazy” is like, how your chick just drives you crazy in some sense and you kinda have to… not necessarily put her in check, but like, as I say, ‘do you know what time it is?’ Funny little reminders that me and my chick have.

I was working on it for a while, and she started humming another song to it. I was like, ‘what are you doing? You’re gonna ruin me!’ She brought it to my attention that it reminded her of another song from this band called Dry & Heavy. So I ended up putting an interpolation of that in “Gone Crazy,” and it just sort of happened. I wasn’t forcing it but it just took form like that. So she kinda helps me. She helped me with “Owens Brothers”. My daughter helped me, too, ‘you should use this word instead of that word,’ that type of thing. Little nuances.

PAN M 360: Are your kids aware of the legacy of your band? Or to that end, do they care?

OO: Yeah, they’re very aware. My front room is an homage to music and I have the Sublime plaques up there. And I have a lot of pictures of Brad, and everybody from all the scenes. So they’re pretty aware of who’s who and why we’re doing what we’re doing. They were laughing like, ‘how come you haven’t put out any music in so long, dad?’ Well, I was kinda raising you guys, you know?

PAN M 360: I’m an old-school Sublime devotee and a huge fan of the first two LBDA records, and it was exciting at that time to get to see and hear your band spin things off and keep going. That said, the new record really stands on its own to capture where LBDA seemed to be headed, back then. How did creative decisions made now lead to bridging that gap?

OO: I think it’s a mix of the fact that we had some songs written and ready to go, and others that we were gonna approach the old Dub Allstars way where, say, I had the chorus, and we asked Moises from Tomorrow’s Bad Seeds, Jack and Tim, and they just kinda pieced together “Easy” in one night. That’s the old LBDA format, where there’s four or five dudes in a room and we just brainstorm, and go, and write.

That’s how [Wonders of the World track] “Lonely End” was born, and a lot of those Dub Allstars songs, that was our formula. This time, we did our homework before, had the songs all ready to go, and then decided who (could help). It was a pretty quick process.

PAN M 360: The first record came out at the end of ’99, when everyone was all paranoid. And the second one came out on 9/11. And now this album is coming out in the middle of a global pandemic and a social revolution. Any reflections on that?

OO: I try not to pay attention. Do you think that Picasso or Salvador Dali cared, when they were debuting their art, if anything was going on in the outside world? (laughs) Probably, to them, they were like, ‘this is the happening. This is the awareness.’

Of course, I mean, you have to be aware, to some extent. And on September 11th, yeah, we did get pretty stifled by that whole deal. This one was gonna drop April 17 and [the band’s management] decided to hold off because I think we knew that shit was gonna get weird. I think this music is more needed now. It’s kind of helping people out, in a sense. [In 2001] we were all so distraught by the news that I don’t even think we were listening to music. But if you think back, Wonders has some of our best work on there.

It’s funny to think back, but now when I look at this one, I feel more accomplished, and the album tells a good story, I feel. Even if it’s just a little reggae and a little ska, it feels right.