Global pandemic, extreme divisions within the anxious Western populations, troubling American presidential elections, we’re going through some of the best ones. We have to be aware that this distressing climate distracts us from the regional tragedies experienced on this small planet…

Take for instance the very violent aggression against the Armenian residents of an autonomous but landlocked region of dictatorial Azerbaijan, whose expansionism is being revived by its Turkish ally. This Armenian enclave is named Artsakh, officially the Republic of Artsakh or Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh. For decades, this territory has been the object of significant tensions, which have been at their highest since the end of September.

One thing is certain, Tigran Hamasyan is very concerned. Certainly the most famous Armenian musician of his generation, the supervirtuoso pianist laments this new ordeal experienced by his people, once again a victim of the powers of the region who are vying for territorial influence – Turkey, Russia, Iran.

Is there any need to recall the genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire of which the Armenians were once victims?

Because Hamasyan is augmenting the supportive actions for which this Facebook page has raised more than a million US dollars, since he launched a video in homage to the martyred couples who fought the Ottoman army in the previous century, PAN M 360 contacted the musician at his Californian home to ask him to express himself on the issue.

“On September 27, this region was attacked pretty much on its entire border by our neighbours from Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey as well – even though Turkey is denying it, but there is so much evidence of it. Thousands of mercenaries from the region have been hired to fight in the border attack. The fact they brought terrorists to the region, creating a lot of hostility, it becomes very fragile in the south Caucasus. Last Tuesday was the heaviest attack since the war began. Even though Russia invited the foreign-affairs ministers of Armenia and Azerbaijan to cease fire for humanitarian purposes, this agreement was violated five minutes after the time it was supposed to start. It is ironic that Azerbaijan says little or nothing about its deaths, which somehow confirms the hiring of Syrian mercenaries. Tens of thousands of people are displaced, at least 600 Armenian men have been killed in combat so far, especially last Tuesday. It is ironic that Azerbaijan says little or nothing about its deaths, which somehow confirms the hiring of Syrian mercenaries.”

Hamasyan felt the call of the country where he was born and raised until his early teens, when his family moved to California and he was able to pursue higher education there, and launch his international career. A few years ago, he moved back to Yerevan to take care of his grandmother and also to recharge his cultural batteries. His identity was revived and, in the current context, he’s very eager to man the barricades.

He sees this violent aggression against Artsakh as an imperialist operation by Turkey, eager to seal its influence in the Turkish-speaking countries of the region, starting with Azerbaijan.

“For a century, Turkey wanted to connect Azerbaijan to its land, so it would have more control of the area. And… ethnically, Turks and Azeris are the same people. Armenia is only a little country around there, its population is the indigenous people of the region. Armenian and other peoples have suffered for a long time at the hands of the Turks and the Ottoman empire -Assyrian, Greek, Kurdish, Lezgins.

” When the Soviet revolution happened, Stalin gave the region to the people actually living in Azerbaijan, they were called the Turks of the Caucasus. Azerbaijan as a nation did not exist – it was made by the Soviets. The real historic Atropatene (which existed long before Turkic tribes came to the area) is today located in Iran. Artsakh has been populated by ethnic Armenian for thousands of years. Even if you did a genetics analysis you would see that. Then Azeris started populating the region more and more. At some point, during the Soviet era in ’88, the whole thing erupted, Armenians started speaking out and did protests. In fact, the Soviet Union and Azerbaijan were slowly getting rid of Armenians. There were no Armenian schools there, no Christian churches were allowed, Armenian identity was going to be eradicated and at some point, Azerbaijani government had a plan to divide/merge Karabagh into 4 different regions of Azerbaijan thus killing any identity of Armenians. So the Armenian community of Nagorno-Karabakh demanded to be part of Armenia, and this created a big conflict. Azerbaijan responded very violently and started killing Armenian people in Azerbaijan. So it’s sad the way the international media are treating this conflict today.”

Like most Armenians aware of the conflict, Hamasyan disapproves of the Turkish government’s game of influence in its support for Azerbaijan, he also laments the cautious support of countries that should be its unwavering allies.

“Unfortunately, not enough nations openly support Armenia in the resurgence of these attacks against our people. Turkey’s participation in NATO, fossil-fuel money, and other geopolitical factors also cloud the issue. Meanwhile, Turkish President Erdogan wants to become the sultan of the Ottoman Empire that fell at the beginning of the previous century. ”

And what does the world have to say about this outbreak of violence? Hamasyan is astonished and disappointed at the media’s reading of the explosive situation in the Artsakh.

“Many international media are talking about the conflict, they’re often saying that the conflict has flared, which is really not the case. They are looking at Azerbaijan and Armenia as equals, which it’s clearly not the case. It’s sad, because it’s always been the agenda to clean the region of Armenians. When the Soviet revolution happened, Stalin gave the region to the people actually living in Azerbaijan, they were called the Turks of the Caucasus. They were living in the Iranian areas, but for thousands of years, there were Armenians living around there, they are indigenous to that territory.”

Hamasyan is well aware that the balance of power is clearly against the Armenian people, at least in the short term. Nevertheless…

“Times are tough, very hard times. Too many people have already died and this is not a fair fight. My country is not armed as Azerbaijan is armed, and supported by Turkey. So it is a completely unfair fight, but you know, Armenians survived this region when it was reduced to a very small country. I can’t say what the chances of victory are on our side, but I can say without hesitation that there is no chance for Armenians to leave the region. There is no way! Roughly speaking, everyone is willing to die to keep this land. Everywhere in Armenia and in the diaspora, we see lines of volunteers ready to fight. Even in his sixties, my own father applied!”

In 2013, Hamasyan returned to Armenia, spent more and more time there and finally settled there permanently. In 2019, he returned to live temporarily in California with his small family, where he is today – more or less against his will.

“I’ve been stuck there since COVID, but I hope to return to Armenia very soon. Of course I keep playing, I’m always creating music, this process doesn’t stop. There are so many projects that I am involved in, traditional Armenian music is still an important part of my musical language even if not all my projects are of Armenian influence.”

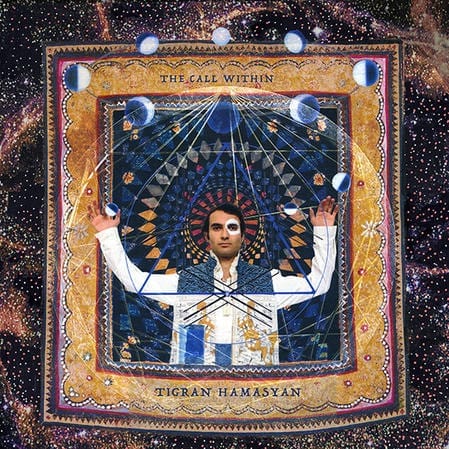

Just a few weeks ago, the prestigious Nonesuch label launched a new opus by Hamasyan, The Call Within, recorded by the pianist alongside bassist Evan Marien and drummer Arthur Hnatek, not to mention a contribution from the Children’s Choir of the Varduhi Art School, and another by guitarist Tosin Abasi.

“I wrote this music to be played by a jazz trio. However, some compositions are done with synthesizers and guests. I would say that the prominent influence of this album is rock – math rock, prog rock, metal.”

And how does Hamasyan intend to fight during this bloody conflict between Artsakh and Azerbaijan? With his music, as you can imagine.

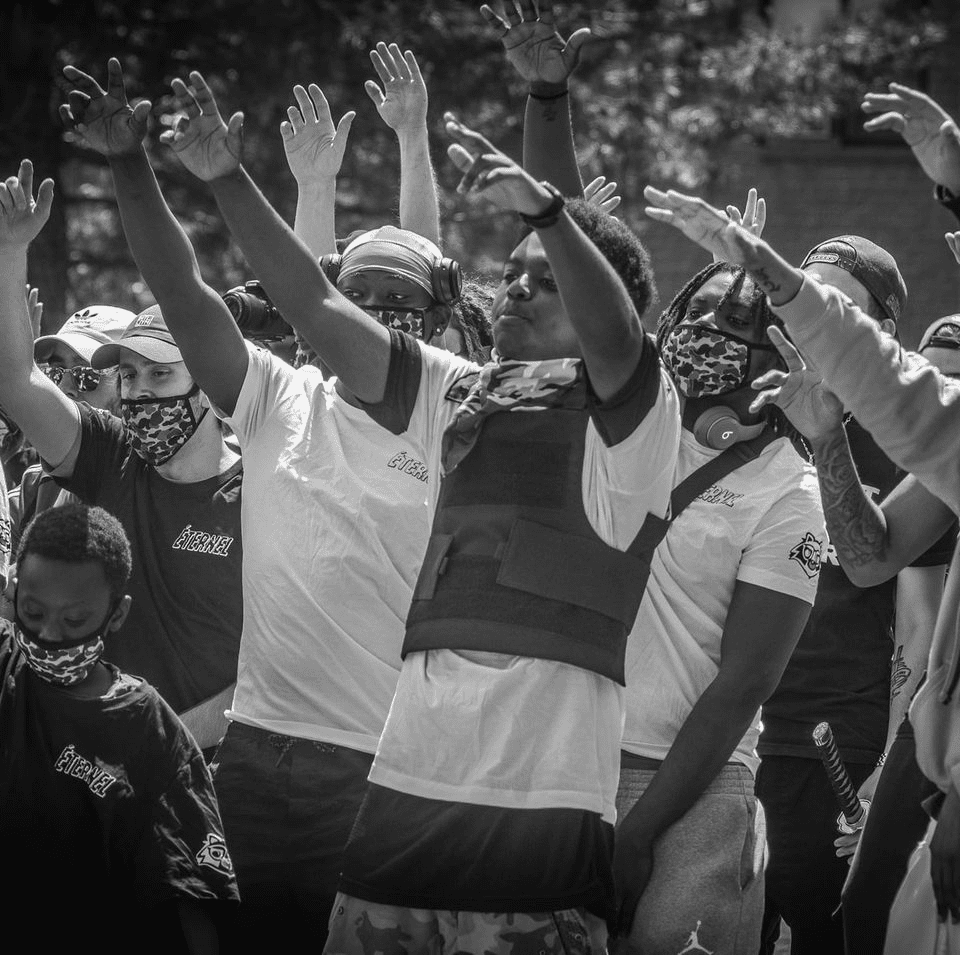

“I’m already doing it with whatever I have. For example, we raised some funds to help out families, completely devastated by death or destruction of their houses. One first fundraising is almost completed, we raised close to a million dollars, and a second fundraising cycle is about to happen. My friends, musicians and artists, will help.”

In this case, music isn’t meant to loosen morals…