Two simultaneous encounters took place yesterday at Salle Bourgie in Montreal: French and Quebec performers of today’s music joined forces, namely Ensemble Variances and Paramirabo, and two presenters, Bourgie itself and Le Vivier, co-produced the event. The concert’s title theme, Pulse, hinted at an evening dedicated to American repetitive music. Pulse is, in fact, the eponymous title of a piece by Steve Reich, a great master of the genre, placed second in the program order.

However, the presence of pulsation as a musical and architectural column was much more subtle and discreet than presumed. The pulsation was much more evoked than hammered home, in these five works written by two women and three men, two of which were world premieres, and one a North American one!

Still Life in Avalanche, by the excellent Missy Mazzoli, immediately fits the idea of repetitive minimalism, but its orchestration makes the beat’s linearity hesitate and hiccup, as well as the piece’s initial tonality. We end up with playful and, yes, pulsating episodes, John Adams-like in their sonorities, but which exchange pre-eminence with other, more mellow, chromatic passages sometimes tending towards the atonal. It sounds like a schizophrenic tango performed by a dysfunctional couple. Very interesting.

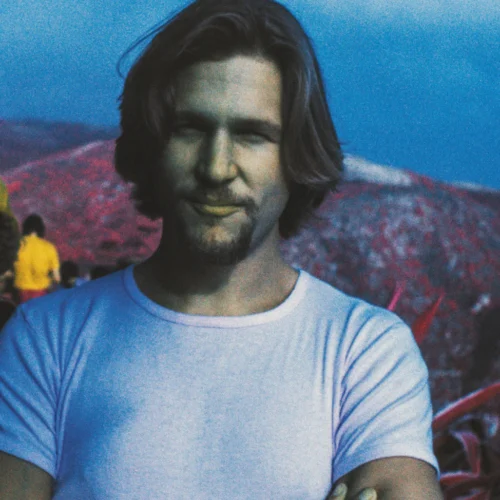

Steve Reich himself, with his own Pulse, relativizes our preconceptions of this music with a piece that appears substantially calmer than his better-known masterpieces such as Music for 18 Musicians, Different Trains, Drumming, Piano Phase and so on. Here, the pulsation so emblematic of the American’s music unfolds more gently and is much less percussive. In fact, there are no percussion instruments at all. The tempo is also slowed down. Reich, yes, but almost Zen-like.

The central pivot of the evening, the piece separating two parts of two pieces each, was Montrealer Marc Patch’s Les Mémoires du miroir de quartz, for solo piano. Composed in 1992, the piece was being performed for the very first time (hence its “world premiere” status!). I still fail to understand its relevance to the logic of the program. It’s a resolutely atonal exercise, made up of dazzling bursts of violent chords, Stockhausen-style, interspersed with passages of pearlescent, luminous cascades. This is more Darmstadt than minimalist New York. That said, don’t misunderstand me: Les Mémoires du miroir de quartz is an excellent piece, played with conviction, technical precision and brilliantly suggested contrasts by Thierry Pécou. But it has nothing to do with the rest. Perhaps, precisely, to create contrast? I have nothing against it, but it could have been explained.

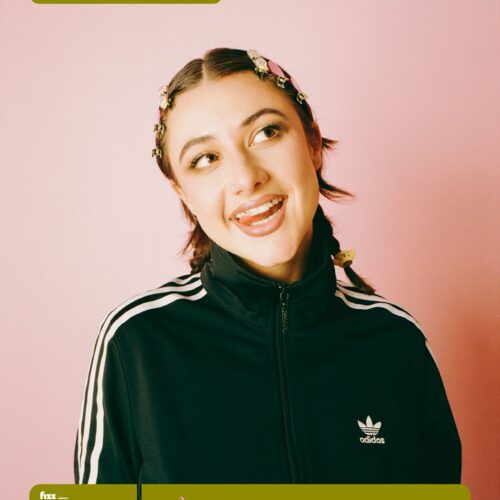

Cassandra Miller, a Montrealer by adoption now living in London, followed with Perfect Offering, a North American premiere. Seemingly straightforward, it’s easy to imagine how extraordinarily difficult it was to set up this piece, which begins as a tribute to the Eno brothers, Brian and Roger. Within the first few minutes, one imagines oneself in Music for Airports, a cult work and founder of contemporary ambient. But unlike the latter, Miller’s piece evolves in a more fleshed-out fashion, swelling with power and resonance, a palpable crescendo that resolves into a false fade-out in the violin and clarinet, the latter becoming increasingly imperceptible, until an infinitesimal pianissimo, a real tour de force from the soloist (Carjez Gerretsen, remarkable). Is this the end? No. We’re off again, with a little more momentum than at the start, and now the pulse is more inviting. The real conclusion is more abrupt than I’d hoped. I think I preferred the false ending with the clarinet’s infinite disappearance. All the same, Perfect Offering, if not perfect, is nonetheless a much-appreciated offering.

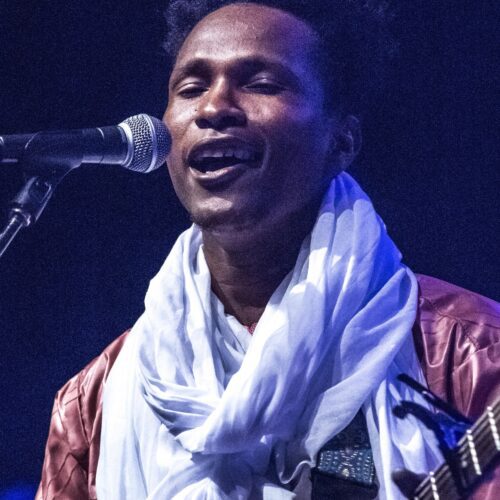

The concert ended with a world premiere, a real one, written in 2023 by Thierry Pécou himself. The two ensembles were invited to perform Byar, inspired by Balinese gamelan music. Several Canadians are known to have been inspired by this music: Colin McPhee, one of the first, and Claude Vivier of course. Pécou summons up some of their visions, but enriches them with many others and emulsifies the whole in the crucible of his own already rich musical personality. Byar is reminiscent of an improbable circular watercourse, made up of tumultuous eddies and marked passages. Coloristic expressionism and structural cohesion inspired by repetition, but often broken up by spontaneous explosions, Byar is a work that I would describe as post-pulsation, post-repetition, or even post-modern, with no compunction about borrowing elements here from the avant-garde and elsewhere from classical minimalism. I need to hear it again to begin to appreciate all its nuances and implications. That’s a good sign.

Excellent performances by the musicians on stage (and often elsewhere in the hall, in multidirectional spatial and sound projection).

The audience, which filled Salle Bourgie to capacity (I’d have liked more, though), applauded warmly, and rightly so.